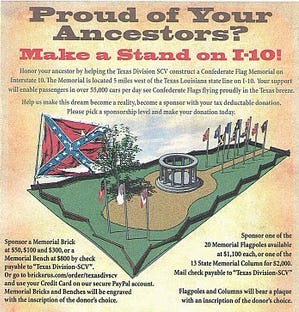

A New Religion: the Noble Confederacy and the Lost Cause

The Roots of White & Christian Nationalism and MAGA

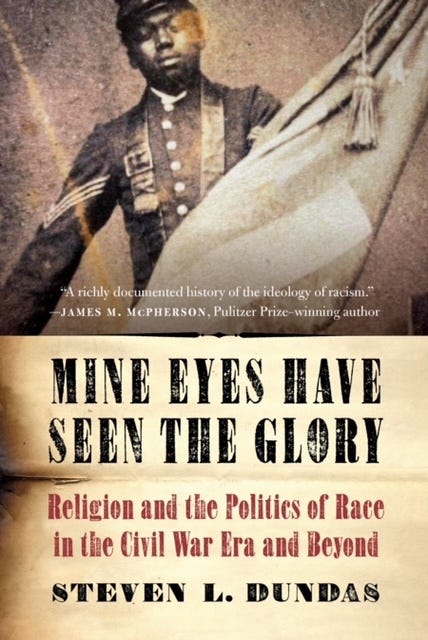

Today I am posting a chapter of my book Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: Religion and the Politics of Race in the Civil War Era and Beyond. The book began as an introductory chapter to my Gettysburg Staff Ride Text, in order for my students to understand the ideologies, secular and religious that motivated the soldiers on both sides to fight. At the time we were still engaged fighting the Islamic State, Al Qaida, and the Taliban, whose religious ideology was built upon centuries of grievances directed towards Western (Christian) nations. By examining the depth of our own divides I hoped to provide a bridge from our history to understand our enemies.

Wars, those fought on battlefields, or culture wars do not occur in a vacuum; they are the result of real and imagined grievances as well as often deep ancient racial, religious, and ideological differences that create divides so deep that they become unbridgeable. We are seeing this today in the culture war that Christian Nationalists, White Nationalists, and MAGA are waging against the advances in civil and religious rights of minorities, and our evolving culture.

While today’s Christian and White Nationalists as well as MAGA are not all from former Confederate States like those that destroyed Reconstruction and established Jim Crow’s 80 year long reign of terror against African Americans, their ideology has its roots in the Antebellum South, particularly the idea of “Liberty for the few, slavery in every form to the mass.”

What follows is a chapter from it dealing with this.

When Edmund Ruffin pulled the lanyard of the cannon that fired the first shot at Fort Sumter, it marked the end of an era. The war that he helped start destroyed it. Ruffin could not abide the Confederacy’s defeat. In a carefully crafted suicide note, the hate-filled man wrote:

“I here declare my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule—to all political, social and business connections with the Yankees and to the Yankee race. Would that I could impress these sentiments, in their full force, on every living Southerner and bequeath them to every one yet to be born! May such sentiments be held universally in the outraged and down trodden South, though in silence and stillness, until the now far-distant day shall arrive for just retribution for Yankee usurpation, oppression and outrages, and for deliverance and vengeance for the now ruined, subjugated and enslaved Southern States! . . . And now with my latest writing and utterance, and with what will be near my last breath, I here repeat and would willingly proclaim my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule—to all political, social and business connections with Yankees, and the perfidious, malignant and vile Yankee race.”

When he lay down his pen, the old fire-eater placed the muzzle of his musket under his chin and blew his brains out.

A Southern Change of Tune

But Ruffin pulled the trigger too soon. Southern states would be free from Yankee rule within a decade. The institution of slavery did not endure, “but southerners’ racial beliefs and habits did. . . . The white ex-Confederate South proved much more successful in guarding this sacred realm” during Reconstruction than during war. Confederates who proclaimed slavery the deciding issue for secession and war changed their story. Slavery was “trivialized as the cause of the war in favor of such things as tariff disputes, control of investment banking and the means of wealth, cultural differences, and the conflict between industrial and agricultural societies.”

Alexander Stephens, author of the infamous Cornerstone Speech, who said in 1861 that “that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition,” now argued that the war was not about slavery, that “it had its origins in opposing principles. . . . It was a strife between the principles of Federation, on the one side, and Centralism, or Consolidation on the other.” He concluded that the American Civil War “represented a struggle between ‘the friends of Constitutional liberty’ and ‘the Demon of Centralism, Absolutism, [and] Despotism!’”

Jefferson Davis changed his belief that the slavery was necessary for the Confederacy’s claim to exist and the reason for secession. The revisionist Davis wrote:

The Southern States and Southern people have been sedulously represented as “propagandists” of slavery and the Northern as the “champions of universal freedom . . .” and “the attentive reader . . . will already found enough evidence to discern the falsehood of these representations, and to perceive that, to whatever extent the question of slavery may have served as an occasion, it was far from being the cause for the conflict.”

Instead of being about slavery, the Confederate cause was mythologized as a lost one: the term “Lost Cause” coined by William Pollard in 1866, which “touching almost every aspect of the struggle, originated in Southern rationalizations of the war.” By 1877 Southerners took as much pride in the Lost Cause as Northerners took in Appomattox. As Alan Nolen writes, “Leaders of such a catastrophe must account for themselves. Justification is necessary. Those who followed their leaders into the catastrophe required similar rationalization.” But honesty and introspection of the real causes was not part of the myth.

Southerners elevated the Lost Cause to the level of a religion that proclaimed the Southern cause as holy. The defeated Confederacy became a national version of Christ, crucified but triumphant over death and the Union. In the new religion,

orthodoxy mattered, both in civil and religious terms: the public symbols of sacrifice were etched into the Southern landscape in the numerous statues, monuments, and consecrated grounds; on the lips of political leaders who reminded their neighbors of that sacrifice and how close they came to suffering the ultimate defeat of Yankee and black rule; in the books and articles they read, primers for remembrance, Aesop’s fables for the masses, with the moral always evident and always the same.

In the Lost Cause, Southerners mythologized and “made sacred the Southern way of life, laying the foundation for a Southern culture religion, a regional faith based upon Dixie’s wartime experience.” In September 1906 Lawrence Griffith told a meeting of United Confederate Veterans that when they returned home they would find that “there was born in the South a new religion.” The Lost Cause took on “the proportions of a heroic legend, a Southern Götterdämmerung with Robert E. Lee as a latter-day Siegfried.” It was was replete with all the signs, symbols, and rituals of religion:

This worship of the Immortal Confederacy had its foundation in myth of the Lost Cause. . . . When it reached fruition in the 1880s its votaries not only pledged their allegiance to the Lost Cause, but they also elevated it above the realm of common patriotic impulse, making it perform a clearly religious function. . . . The Stars and Bars, “Dixie,” and the army’s gray jacket became religious emblems, symbolic of a holy cause and of the sacrifices made on its behalf. Confederate heroes also functioned as sacred symbols: Lee and Davis emerged as Christ figures, the common soldier attained sainthood, and Southern women became Marys who guarded the tomb of the Confederacy and heralded its resurrection.

Jefferson Davis became an incarnational figure in this new faith. The president so maligned during the war became its Christ figure. Southerners believed “was the sacrifice selected—by the North or by Providence—as the price for Southern atonement. Pastors theologized about his ‘passion’ and described Davis as a ‘vicarious victim’ . . . who stood mute as Northerners ‘laid on him the falsely alleged iniquities of us all.’” Instead of a traitor, Davis became a martyr wrongly condemned. A 1923 song about Davis repeated the theme: “Jefferson Davis Still we honor thee! / Our Lamb victorious, who for us endur’d a cross of martyrdom / a crown of thorns, soul’s Gethsemane, a nation’s hate, A dungeon’s gloom! Another God in chains.”

The myth of the Noble South painted a picture of slavery being benevolent as Southerners contended that slaves liked their status. They echoed Hiram Tibbetts’s words to his brother in 1842: “If only the abolitionists could see how happy our people are. . . . The idea of unhappiness would never enter the mind of any one witnessing their enjoyments,” and Davis’s response to the Emancipation Proclamation, calling the slaves “peaceful and contented laborer.”

The romantic images of the Lost Cause were conveyed to the American public as fact by writers and Hollywood producers. Thomas Dixon Jr.’s 1905 play and novel The Clansman became D. W. Griffith’s 1915 film epic The Birth of a Nation started the nationwide trend. The film was a groundbreaking event in American cinematography that portrayed white Southerners as nobly fighting against Yankee invaders, rapacious Blacks, and bloodsucking carpetbaggers. After Woodrow Wilson, the first president from the South since Zachary Taylor, screened it in White House, Wilson proclaimed, “It is like writing history with lightening, and one of my regrets it is so horribly true.”

The film was very popular in Northern cities and in the West, where it “generated its largest profits,” and in areas where war’s memory had long since faded. “Patrons were likely dazzled by Griffith’s technical skill and masterful staging and little bothered by his racism.” The crowds that clamored for seats to The Birth of a Nation “were not only a testimony to the director’s artistic genius, but also evidence of a lack of interested in solving the nation’s racial problems.”

Non-Southerners “willingly adopted and even enhanced the southern memory of the war and the Reconstruction era.” Some, like Henry Cabot Lodge, condemned “the tendency of northerners to accept uncritically the southern perspective on the war and Reconstruction.” But the myth of the Noble South appealed to Northerners who shared Southern views amid waves of immigrants and free Blacks. Northerners “cherished the manufactured South precisely because it was not the North: a genteel, rural, homogenous, and harmonious region of languid days and starry nights where people moved as softly as the breeze on a summer evening and where paternalism counted more that profit.” In a New York showing of Griffiths’s film, “people were moved to cheers, hisses, laughter, and tears, apparently unconscious, and subdued by the intense interest of the play.” They “clapped when the masked riders took vengeance on the Negroes,” and “when the hero refused to shake the hand of a mulatto.” The film added to the movement in the North and West to form what became known as “sundown towns,” where Blacks were driven out or were specifically built to keep Blacks and other minorities out.

The Birth of a Nation remained the most popular film in America, particularly the South, for the next twenty years. It lost its place when Margaret Mitchell published her epic novel Gone with the Wind in 1936. The book sold over seven million copies and Mitchell received a Pulitzer Prize. Producer David O. Selznick purchased the books rights and turned it an epic film production that was released in December 1939, starring some of the biggest names in Hollywood, including Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh, Olivia de Havilland, and Leslie Howard, as well as notable Black actress Hattie McDaniel. Masterfully filmed in color, it smashed box office records and won ten Academy Awards, and it immortalized the antebellum South with images of kind masters, faithful slaves, noble soldiers, and virtuous women, struggling to defend their way of life against the brutal Yankees. “Hollywood gossip columnist Luella Parsons called Gone with the Wind ‘the best thing since Birth of a Nation.’”

Griffith’s film was marked by crude racism, but Selznick adopted a more romantic and genteel portrayal of racism than Griffith in Gone with the Wind, that of “a paternalistic treatment of slavery that would have pleased the original Lost Cause warriors.” The film painted the South after the Civil War as an ideal, with the war a tragedy and Reconstruction a crime. It was a remarkable film of great cinematographic grandeur, and audiences were swept away as they took in its mythical story of the Old South and passing of a society that was one of “wealth and distinction,” with attendant “hospitable manners, broad acres, beautiful women and chivalrous men and the faithful old mammies that served them.” Gone was any realistic portrayal of the cruelty of slavery and the fact that, immediately after the war, Southern landowners returned to reenslaving Blacks by other means.

The films also fed into a national mythology that legitimized Jim Crow and racial prejudice against Blacks. “Birth of a Nation, the first great epic, valorized the Ku Klux Klan. So did the film verson of Gone with the Wind, the first great color feature and still the most successful film of all time. No longer were secessionists villains; now abolitionists played that role.” Griffith’s cinematographic masterpiece “lionized the first Ku Klux Klan (1865–75) as the savior of white southern civilization and fueled a nationwide Klan revival. Near the end of the nadir in 1936, Gone with the Wind sold a million hardbound books in its first month; the book and the resulting film, the highest-grossing movie of all times, further convinced whites that noncitizenship was appropriate for African Americans.”

The most powerful effect of the films was their propaganda value, which shaped the views of millions of people who had little or no contact with Blacks and whose “introduction to African-American history was molded on as much by cinematic fiction as by personal contact and knowledge.” It would not be until the late 1940s and the 1950s when Hollywood producers released The Foxes of Harrow (1947), A Band of Angels (1956), and Shenandoah (1965) that films portraying the dark side of slavery began to appear. To Kill a Mockingbird (1964) helped many to see the injustice and violence of Jim Crow; Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles (1974), which became a beloved cult classic, used comedy to expose racism; Glory (1989) portrayed the sacrifice of valiant Black soldiers of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment at Fort Wagoner, while A Soldier’s Story (1984), a murder mystery in an all-Black unit on a base in the Deep South in 1944, depicted Black soldiers in the segregated army of World War II. Steven Spielberg’s The Color Purple (1985) depicted the life of two Black teenage girls in abusive homes in 1920s Georgia, while Django Unchained (2012) showed the violence of plantation slavery and the interstate slave trade. Television began to retell the evils of slavery in The Diary of Miss Jane Pittman (1974), the story of a former slave recounting her life during the civil rights movement, and Alex Haley’s masterpiece miniseries Roots (1977). Since those early productions, many television shows and movies have broken new ground for Black actors in nonstereotyped leading roles, making many household names with strong voices for civil rights.

The Divide

A T-Shirt sold at a gift shop in Gettysburg

The Lost Cause comforted and inspired Southerners following the war: “It defended the old order, including slavery (on the grounds of white supremacy) and in Pollard’s case even predicted that the superior virtues of cause it to rise ineluctably from the ashes of its unworthy defeat.” The myth paved the way for over a century of second-class citizenship for Blacks, deprived of the vote and forced into “separate but equal” schools, hospitals, and recreational centers, as the KKK intimidated, persecuted, attacked, and lynched Blacks. However, many Union veterans fought the Lost Causers to the day they died. Members of the Grand Army of the Republic, the first truly national veteran’s organization and the first to admit Black soldiers as equals, continued their fight to keep the public fixed on the reason for war. They point out the profound difference between what they and the Confederates fought:

The Society of the Army of the Tennessee described the war as a struggle “that involved the life of the Nation, the preservation of the Union, the triumph of liberty and the death of slavery. They had fought every battle . . . from the firing on the Union flag Fort Sumter to the surrender of Lee at Appomattox . . . in the cause of human liberty,” burying “treason and slavery in the Potter’s Field of nations” and “making all our citizens equal before the law, from the gulf to the lakes, and from ocean to ocean.”

In 1937 the last great Blue and Gray Reunion was held at Gettysburg. Surviving members of the United Confederate Veterans extended an invitation to the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) to join them. Members of the GAR’s Seventy-First Encampment from Madison, Wisconsin, which included survivors of the immortal Iron Brigade, who sacrificed so much at Gettysburg, adamantly opposed the display of the Confederate Battle flag at the reunion. “No Rebel colors,” they shouted. “What sort of compromise is that for Union soldiers but hell and damnation.”

Edmund Ruffin outlived Lincoln by a few months. Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865. To his death by suicide, Ruffin remained bitter and full of hate, but that was not the case with Lincoln, who seemed incapable of hating his enemies. In his second inaugural address, Lincoln spoke in a completely different manner, concluding with these words: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

If you haven’t yet gotten the book there are several ways to do so. If you become or upgrade to being a Founding Member of Dedicated to the Proposition that All are Created Equal I will send you an inscribed copy. You can also purchase the book in online or brick and mortar bookstores. If you would like to do a review of it for a publication you are associated with, please let me know and I will provide a copy. Lastly, if you would like to interview me for a print article, podcast, or radio or television station, or speak at an event dealing with this subject, please contact me.

Newspaperman Edward Pollard was the one who coined the phrase "lost cause," not William Pollard.