After This Civil War, Will there be Reconciliation?

Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Ely Parker Show Us a Way to Begin

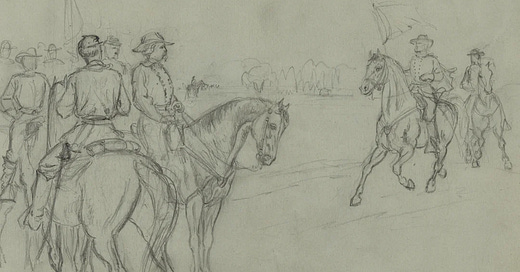

William Ward’s illustration of a Confederate Emissary under a white flag bringing Lee’s request to meet Grant to surrender being delivered to George Armstrong Custer.

Ever since Donald Trump lost the 2020 election the United States has been devolving into a state of civil war. While the violence has largely been restrained since the unprecedented attack on the Capitol on 6 January 2021, the violent sentiments, especially on the part of Trump, whose words are soaked in the violent imagery of revenge, retribution and conquest have poisoned the social and political climate so much that we are getting close to a civil war like that of Ireland and the “troubles” of Northern Ireland. This war will not have traditional battle lines or military actions, but it promises to be bloody and unforgiving.

In his actions since his inauguration Trump has launched a Blitzkrieg across the country decimating the Federal Government, reversing civil rights, and destroying the lives and fortunes of Americans, including many of those who voted for him. The catalog of those actions is now so vast that it is impossible to chronicle them in a single article and they grow increasingly harsh, threatening basic constitutional protections and rights. The actions of deporting immigrants like so much chattel, even legal immigrants and those offered refuge in the United States from war, famine and oppressive police states, including Communist countries goes against every sense of decency and liberty the United States once represented. Our history is being erased before our very eyes by White and Christian Nationalist zealots determined to erase the contributions of all Americans except Whites. Again the scope of this is overwhelming and more attacks on our history as Americans are happening every day at the Smithsonian, the National Park Service, the Justice Department and in the military where Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, an avowed White and Christian Nationalist completely set on eliminating the gains of minorities and women in the military and erasing their stories from military schools including the service academies, historical divisions of the services, and the websites of such places as Arlington National Cemetery are directed against real history and scholarship. It as if the Sons and Daughters of the Confederacy are being allowed to return the telling of history to what it was in the early to mid-20th Century when most American history was written and taught by apologists for the Confederacy and White Supremacy.

I am invested in this fight for history and civil rights and will not back down. I also believe that Trump’s MAGA revolution is destined to fail, but that it will cause much suffering and damage to our nation and people, and damage that will take years and maybe decades to recover from. Healing will take even longer, but we must begin to think about it. Thus I write about the surrender of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant’s Federal Armies at Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865, one hundred sixty years ago tomorrow. So now I remember a moment in time that held so much promise which was devastated by the assassination of Abraham Lincoln just 5 days later.

One hundred and fifty four years ago on the 9th and 10th of April 1865, four men, Ulysses S Grant, Robert E. Lee, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Ely Parker, taught succeeding generations of Americans the value of mutual respect and reconciliation. The four men, each very different, would do so after a bitter and bloody war that had cost the lives of over 600,000 Americans and which had left hundreds of thousands others maimed, shattered or without a place to live. Likewise, vast swaths of the country were ravaged by the war and its attendant plagues.

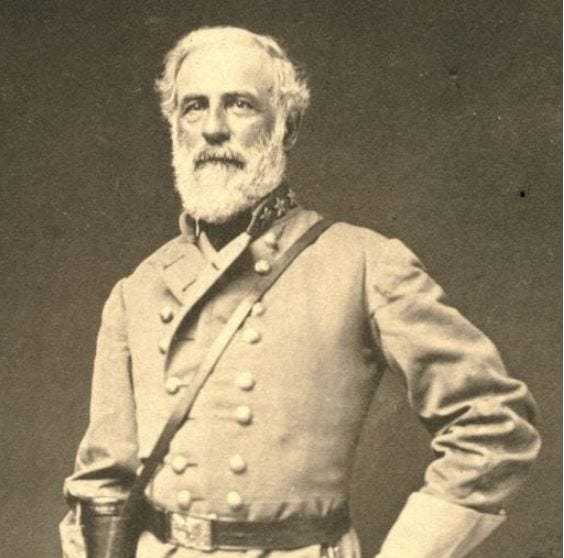

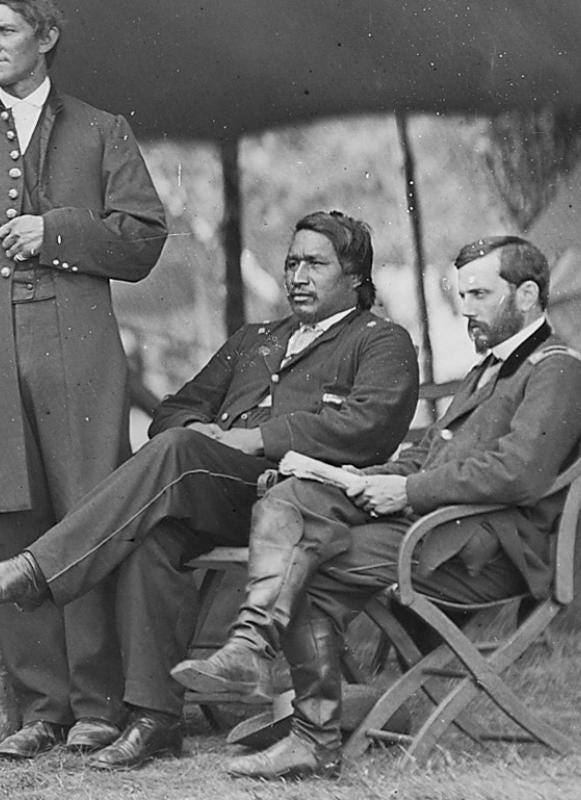

The differences in the men, their upbringing, and their views about life seemed to be insurmountable. The Confederate commander, General Robert E. Lee was the epitome of a Southern aristocrat and career army officer. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, like Lee was a West Point graduate and veteran of the War with Mexico, but there the similarities ended. Grant was an officer of humble means who had struggled with alcoholism and failed in his civilian life after he left the army, before returning to the Army as a volunteer when war began. Major General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain had been a professor of rhetoric and natural and revealed religion at Bowdoin College in Maine until early 1862 when he volunteered to serve. He was a hero of Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg, who helped exemplify the importance of citizen soldiers in peace and war. Finally there was Colonel Ely Parker, a full-blooded Seneca Indian; a professional engineer by trade, a man who was barred from being an attorney because as a Native American he was not a citizen. He had been rejected from serving in the army for the same reason, but, his friend Grant obtained him a commission and made him a member his staff.

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, United States Army

A few days before, the Confederate line around the fortress of Petersburg was shattered at the battle of Five Forks. In an attempt to save the last remnants of his army, Lee attempted to withdraw to the west. Within a few days the once magnificent Army of Northern Virginia was trapped near the town of Appomattox. On the morning of April 9th 1865 Lee replied to an entreaty of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant requesting that he and his Army of Northern Virginia be allowed to surrender. Lee wrote to Grant:

I received your note of this morning on the picket-line, whither I had come to meet you and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced in your proposal of yesterday with reference to the surrender of this army. I now ask an interview in accordance with the offer contained in your letter of yesterday for that purpose.

R.E. LEE, General.

The once mighty Army of Northern Virginia, which had won so many victories and which at its peak numbered nearly 80,000 men, was now a haggard, emaciated, yet still proud force of about 15,000 soldiers. For Lee to continue the war would mean that they would face hopeless odds against a vastly superior enemy. Grant recognized this and wrote Lee:

I am equally anxious for peace with yourself, and the whole North entertains the same feeling. The terms upon which peace can be had are well understood. By the South laying down their arms they will hasten that most desirable event, save thousands of human lives, and hundreds of millions of property not yet destroyed. Seriously hoping that all our difficulties may be set-tied without the loss of another life, I subscribe myself, &c.,

Since the high water mark at Gettysburg on 3 July 1863, Lee’s army had been on the defensive. Lee’s ill-fated offensive into Pennsylvania was one two climactic events that sealed the doom of the Confederacy on July 4th 1863, when Grant’s received the surrender of a Confederate army at Vicksburg the day after Pickett’s Charge. That victory cut the Confederacy in half. Lincoln made Grant the Commander of all Union armies in January 1864 and Grant made his headquarters with George Meade’s Army of the Potomac, leaving Henry Halleck to be his link to the other armies fighting the Confederacy.

General Robert E. Lee, Confederate States Army

The bloody defensive struggle in the East lasted through 1864 as Grant bled the Confederates dry during the Overland Campaign. This lead to the long siege of Petersburg. Likewise the armies of William Tecumseh Sherman had cut a swath through Georgia and the Deep South and were moving toward Virginia from the Carolinas. Sherman’s offensive so demoralized many Confederate soldiers that they deserted in ever increasing numbers, leading Lee to order summary executions of deserters at Petersburg.

With each battle following Gettysburg the Army of Northern Virginia became weaker. Finally, when the nine month long siege of Petersburg ended with a Union victory there was little else to do. Lee’s Army was now surrounded at Appomattox, Federal Cavalry bared their escape to the west as Grant attempted to persuade Lee to surrender. On the morning of April 9th, Lee ordered a final attempt to break through the Union lines by John Gordon’s division. Gordon’s attack was turned back by vastly superior Union forces.

On April 7th Grant wrote a letter to Lee, which began the process of ending the war in Virginia. He wrote:

General R. E. LEE:

The result of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the C. S. Army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.

U.S. GRANT, Lieutenant-General

Lee was hesitant to surrender knowing Grant’s reputation for insisting on unconditional surrender, terms that Lee could not accept. He replied to Grant:

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA, APRIL 7, 1865 Lieut. Gen. U.S. GRANT:

I have received your note of this date. Though not entertaining the opinion you express on the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia, I reciprocate your desire to avoid useless effusion of blood, and therefore, before considering your proposition, ask the terms you will offer on condition of its surrender.

R.E. LEE, General.

Their correspondence continued over the next day even as the Confederates tried to fight their way out of the trap that they were in. But now on this Palm Sunday, Robert E. Lee, who had through his efforts extended the war for at least six months, knew that he could no longer continue. Even so some of his younger subordinates wanted to continue the fight. When his artillery chief Porter Alexander recommended that the Army be released, “take to the woods and report to their state governors” Lee replied:

“We have simply now to face the fact that the Confederacy has failed. And as Christian men, Gen. Alexander, you & I have no right to think for one moment of our personal feelings or affairs. We must consider only the effect which our action will have upon the country at large.”

Lee continued:

“Already [the country] is demoralized by the four years of war. If I took your advice, the men would be without rations and under no control of their officers. They would be compelled to rob and steal in order to live…. We would bring on a state of affairs it would take the country years to recover from… You young fellows might go bushwhacking, but the only dignified course for me would be to go to General Grant and surrender myself and take the consequences of my acts.”

Alexander was so humbled at Lee’s reply he later wrote “I was so ashamed of having proposed such a foolish and wild cat scheme that I felt like begging him to forget he had ever heard it.” When Alexander saw the gracious terms of the surrender he was particularly impressed with how non-vindictive the terms were, especially in terms of parole and amnesty for the surrendered soldiers.

Abraham Lincoln had already set the tone for the surrender in his Second Inaugural Address given just over a month before the surrender of Lee’s army. Lincoln closed that speech with these words of reconciliation.

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Colonel William Forsyth, aide-de-camp to Major General Philip Sheridan whose cavalrymen defeated the final Confederate attack received messenger who carried Lee’s request to meet Grant passed it to Sheridan. Grant arrived about an hour later. Forsyth wrote:

“When within a few yards of us he drew rein, and halted in front of General Sheridan, acknowledged our salute, and then, leaning slightly forward in his saddle, said, in his usual quiet tone, “Good morning, Sheridan; how are you ?”

“First-rate, thank you, General,’ was the reply. “How are you?”

General Grant nodded in return, and said, “Is General Lee up there?” indicating the courthouse by a glance.

“Yes,” was the response, “he’s there.”

“Very well, then,” said General Grant. “Let’s go up.”

General Sheridan, together with a few selected officers of his staff, mounted, and joined General Grant and staff. Together they rode to Mr. McLean’s house, a plain two-story brick residence in the village, to which General Lee…was known to be awaiting General Grant’s arrival.”

Lee met Grant at the house of Wilmer McLean, who had moved to Appomattox in 1861 after his home near Manassas had been used as a Confederate headquarters during the Battle of Bull Run was damaged by artillery fire. Seeking a safer place to live, he moved to Appomattox far away from northern Virginia and the war.

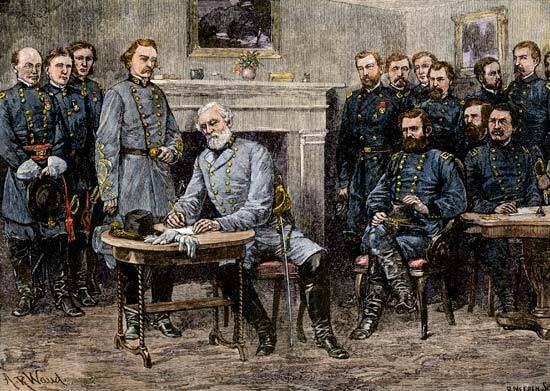

Lee was waiting when arrived. He dressed in his finest uniform complete with sash, while Grant was dressed in a mud splattered uniform and overcoat only distinguished from his soldiers by the three stars on his should boards. Grant’s dress uniforms were far to the rear with the baggage trains and Grant was afraid that his slovenly appearance would insult Lee, but it did not. It was a friendly meeting, before getting down to business the two reminisced about the Mexican War.

Grant provided his vanquished foe very generous surrender terms:

“In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th inst., I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of N. Va. on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate. One copy to be given to an officer designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their commands. The arms, artillery and public property to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.”

When Lee left the building Federal troops began cheering but Grant ordered them to stop. Grant felt a sense of melancholy and wrote “I felt…sad and depressed, at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people has fought.” He later noted: “The Confederates were now our countrymen, and we did not want to exult over their downfall.”

Lee departing the McLean House

In the hours before and after the signing of the surrender documents old friends and classmates, separated by four long years of war gathered on the porch or around the house. Grant and others were gracious to their now defeated friends and the bitterness of war began to melt away. Some Union officers offered money to help their Confederate friends get through the coming months. It was an emotional reunion, especially for the former West Point classmates gathered there.

“It had never been in their hearts to hate the classmates they were fighting. Their lives and affections for one another had been indelibly framed and inextricably intertwined in their academy days. No adversity, war, killing, or political estrangement could undo that. Now, meeting together when the guns were quiet, they yearned to know that they would never hear their thunder or be ordered to take up arms against one another again.”

Grant sent 25,000 rations to the starving Confederate army as it waited to surrender. The gesture meant much to the defeated Confederate soldiers who had had little to eat ever since the retreat from Petersburg began.

The surrender of the Confederate army was accomplished with a recognition that only soldiers who have given the full measure of devotion can know when confronting a defeated enemy. Major General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, the heroic victor of Little Round Top, and now a division commander was directed by Grant to receive the final surrender of the defeated Confederate infantry on the morning of April 12th.

It was a rainy and gloomy morning as the beaten Confederates marched to the surrender grounds. As the initial units under the command of Major General John Gordon passed him, Chamberlain was moved with emotion he ordered his soldiers to salute the defeated enemy for whose cause he had no sympathy. Chamberlain honored the defeated Rebel army by bringing his division to present arms.

John Gordon, who was “riding with heavy spirit and downcast face,” looked up, surveyed the scene, wheeled about on his horse, and “with profound salutation returned the gesture by lowering his saber to the toe of his boot. The Georgian then ordered each following brigade to carry arms as they passed third brigade, “honor answering honor.”

Major General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, pictured as a Brigadier General

Chamberlain was not just a soldier. Before the war he was Professor of Natural and Revealed Religions at Bowdoin College in Maine. He was student of theology before the war, but did not seek ordination. However, he could not help to see the significance of the occasion. He understood that some people would criticize him for saluting the surrendered enemy. However, Chamberlain, unlike others, understood the value of reconciliation, which was central to his understanding of the Christian faith. Chamberlain was also a staunch abolitionist who hated slavery and a devout Unionist who believed that the Confederate rebellion was evil. He nearly died on more than one occasion fighting the defeated Confederate Army, and he understood that no true peace could transpire unless the enemies became reconciled to one another.

He noted that his chief reason for doing so:

“The momentous meaning of this occasion impressed me deeply. I resolved to mark it by some token of recognition, which could be no other than a salute of arms. Well aware of the responsibility assumed, and of the criticisms that would follow, as the sequel proved, nothing of that kind could move me in the least. The act could be defended, if needful, by the suggestion that such a salute was not to the cause for which the flag of the Confederacy stood, but to its going down before the flag of the Union. My main reason, however, was one for which I sought no authority nor asked forgiveness. Before us in proud humiliation stood the embodiment of manhood: men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve; standing before us now, thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking level into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond;—was not such manhood to be welcomed back into a Union so tested and assured? Instructions had been given; and when the head of each division column comes opposite our group, our bugle sounds the signal and instantly our whole line from right to left, regiment by regiment in succession, gives the soldier’s salutation, from the “order arms” to the old “carry”—the marching salute. Gordon at the head of the column, riding with heavy spirit and downcast face, catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up, and, taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command, gives word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position of the manual,—honor answering honor. On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer, nor word nor whisper of vain-glorying, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead!”

On 10 April, Robert E Lee addressed his soldiers for the last time. Lee’s final order to his loyal troops was published the day after the surrender. It was a gracious letter of thanks to men that had served their beloved commander well in the course of the three years since he assumed command of them outside Richmond in 1862. His General Order #9 stated:

After four years of arduous service marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.

I need not tell the survivors of so many hard fought battles, who have remained steadfast to the last, that I have consented to the result from no distrust of them.

But feeling that valour and devotion could accomplish nothing that could compensate for the loss that must have attended the continuance of the contest, I have determined to avoid the useless sacrifice of those whose past services have endeared them to their countrymen.

By the terms of the agreement, officers and men can return to their homes and remain until exchanged. You will take with you the satisfaction that proceeds from the consciousness of duty faithfully performed, and I earnestly pray that a merciful God will extend to you his blessing and protection.

With an unceasing admiration of your constancy and devotion to your Country, and a grateful remembrance of your kind and generous consideration for myself, I bid you an affectionate farewell. — R. E. Lee, General

The surrender was the beginning of the end. Other Confederate forces continued to resist for several weeks, but with the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia led by the man that nearly all Southerners saw as the embodiment of their nation the war was effectively over.

Lee had fought hard and after the war was still under the charge of treason, but he understood the significance of defeat and the necessity of moving forward as one nation. In August 1865 Lee wrote to the trustees of Washington College of which he was now President:

“I think it is the duty of every citizen, in the present condition of the Country, to do all in his power to aid the restoration of peace and harmony… It is particularly incumbent upon those charged with the instruction of the young to set them an example of submission to authority.”

Brigadier General Ely Parker

It is a lesson that all of us in our terribly divided land need to learn regardless of or political affiliation or ideology. After he had signed the surrender document, Lee learned that Grant’s Aide-de-Camp Colonel Ely Parker, was a full-blooded Seneca Indian. He stared at Parker’s dark features and said: “It is good to have one real American here.”

Parker, a man whose people had known the brutality of the white man, a man who was not considered a citizen and would never gain the right to vote, replied, “Sir, we are all Americans.” That afternoon Parker would receive a commission as a Brevet Brigadier General of Volunteers, making him the first Native American to hold that rank in the United States Army. He would later be made a Brigadier General in the Regular Army.

I don’t know what Lee thought of that. His reaction is not recorded and he never wrote about it after the war, but it might have been in some way led to Lee’s letter to the trustees of Washington College. I think with our land so divided, ands that is time again that we learn the lessons so evidenced in the actions and words of Ely Parker, Ulysses Grant, Robert E. Lee and Joshua Chamberlain, for we are all Americans.

Our new civil war is only just beginning. I have no idea how long it will last, but I am convinced that Trump and his MAGA movement will fail, but they will do lasting damage before they are done. The question is, once they are defeated how do we bring the vanquished back in order that years from now our descendants will not experience such travail yet again.

Maybe it is far too early for most of us to even contemplate such an action. However, when we are ready, I think that these four men and others like them point a way.

Until next time, be safe and watch your six.

Heartbreaking rendering, adding to the absurdity of human slaughter.

This next time we can blame it on AI, but we all know just who's responsible

for setting in motion, Death's Dance.

Steve,

Thank you for your profound essay.

I hear every word.

We have much to learn from you.

It is not too early to contemplate.

"We are all Americans"

must be our watchword.

Before during and after

the hell that is to come.