Don’t Forget Black History Month: The Heroes of the U.S. Colored Troops Part Two

Fight Trump and His Racist Agenda

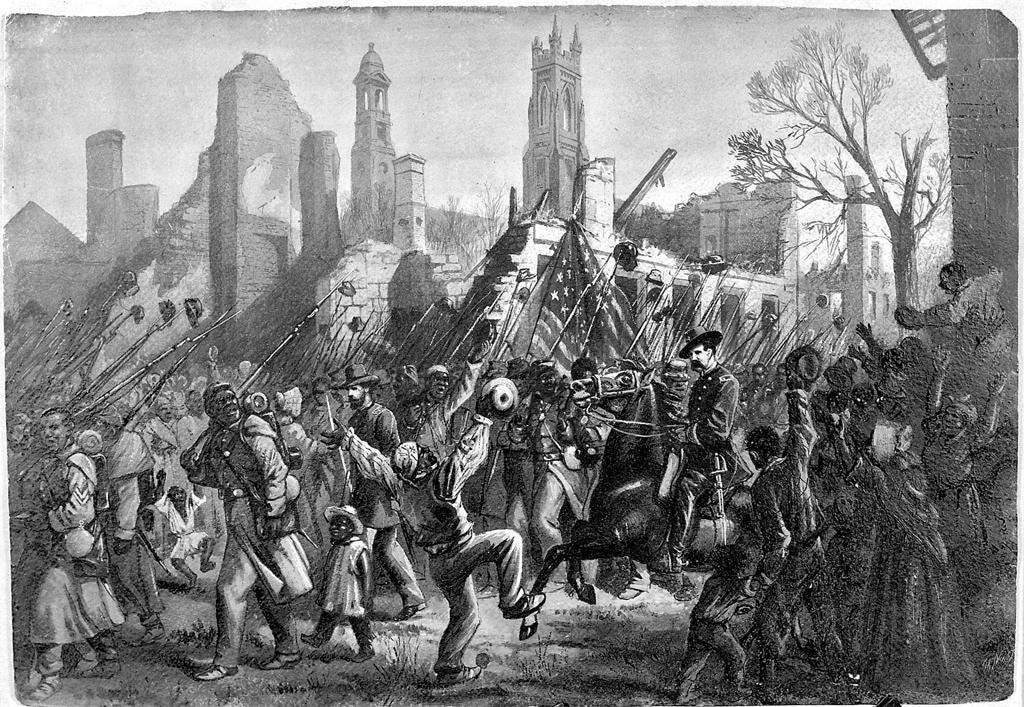

The 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment Enters Charleston, South Carolina, 21 February 1865

In the 55th Massachusetts, which was recruited after the 54th, twenty-one year old Sergeant Isaiah Welch wrote a letter which was published in the Philadelphia Christian Recorder from Folly Island South Carolina:

“I will mention a little about the 55th Massachusetts Regiment. They seem to be in good health at the present and are desirous of making a bold dash upon the enemy. I pray God the time will soon come when we, as soldiers of God, and of our race and country, may face the enemy with boldness. For my part I feel willing to suffer all privations incidental to a Christian and a soldier…. In conclusion, let me say, if I fall in the battle anticipated, remember, I fall in defense of my race and country. Some of my friends thought it very wrong of me in setting aside the work of the Lord to take up arms against the enemy…. I am fully able to answer all questions pertaining to rebels. If taking lives will restore the country to what it once was, then God help me to slay them on every hand.” [45]

Like the 54th Massachusetts, the 55th would see much action. After one particularly sharp engagement in July 1864, in which numerous soldiers had demonstrated exceptional valor under fire the regiment’s commander, Colonel Alfred S. Hartwell “recommended that three of the black sergeants of the 55th be promoted to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant.” But Hartwell’s request was turned down, and a member of the regiment complained, “But the U.S. government has refused so far to must them because God did not make them White…. No other objection is, or can be offered.”[46]

But the premier leader of the African Americans of his day, who had himself suffered as a slave, did not stop with that. Douglass understood that winning the war was more important that to what had been the attitude of the Federal government before the war and before emancipation, “Now, what is the attitude of the Washington government towards the colored race? What reasons have we to desire its triumph in the present contest? Mind, I do not ask what was its attitude towards us before the war…. I do not ask you about the dead past. I bring you to the living present.” He noted the advances that had been made in just a few months and appealed to his listeners. “Do not flatter yourselves, my friends, that you are more important to the Government than the Government to you. You stand but as the plank to the ship. This rebellion can be put down without your help. Slavery can be abolished by white men: but liberty so won for the black man, while it may leave him an object of pity, can never make him an object of respect…. Young men of Philadelphia, you are without excuse. The hour has arrived, and your place is in the Union army. Remember that the musket – the United States musket with its bayonet of steel – is better than all the mere parchment guarantees of liberty. In your hands that musket means liberty…” [49]

Many other African American units less famous than the illustrious 54th Massachusetts or the 55th, distinguished themselves in action against Confederate forces. Two regiments of newly recruited blacks were encamped at Milliken’s Bend Louisiana when a Confederate brigade attempting to relieve the Vicksburg garrison attacked them. The troops were untrained and ill-armed but held on against a determined enemy:

“Untrained and armed with old muskets, most of the black troops nevertheless fought desperately. With the aid of two gunboats they finally drove off the enemy. For raw troops, wrote Grant, the freedmen “behaved well.” Assistant Secretary of War Dana, still with Grant’s army, spoke with more enthusiasm. “The bravery of the blacks,” he declared, “completely revolutionized the sentiment in the army with regard to the employment of negro troops. I heard prominent officers who had formerly in private had sneered at the idea of negroes fighting express after that as heartily in favor of it.”[50]

The Battle of Milliken’s Bend

The actions of the black units at Milliken’s bend attracted the attention and commendation of Ulysses Grant, who wrote in his cover letter to the after action report, “In this battle most of the troops engaged were Africans, who had little experience in the use of fire-arms. Their conduct is said, however, to have been most gallant, and I doubt not but with good officers that they will make good troops.” [51] They also garnered the attention of the press. Harper’s published an illustrated account of the battle with a “double-page woodcut of the action place a black color bearer in the foreground, flanked by comrades fighting hand-to-hand with Confederates. A brief article called it a “the sharp fight at Milliken’s bend where a small body of black troops with a few whites were attacked by a large force of rebels.” [52] In the South the result was chilling and shocked whites, one woman wrote “It is hard to believe that Southern soldiers – and Texans at that – have been whipped by a mongrel crew of white and black Yankees…. There must be some mistake.” While another woman in Louisiana confided in her diary, “It is terrible to think of such a battle as this, white men and freemen fighting with their slaves, and to be killed by such a hand, the very soul revolts from it, O, may this be the last.” [53]

Louisiana Native Guards at Port Hudson

By the end of the war over 179,000 African American Soldiers, commanded by 7,000 white officers served in the Union armies. For a number of reasons most of these units were confined to rear area duties or working with logistics and transportation operations. The policies to regulate USCT regiments to supporting tasks in non-combat roles “frustrated many African American soldiers who wanted a chance to prove themselves in battle.” [54] Many of the soldiers and their white officers argued to be let into the fight as they felt that “only by proving themselves in combat could blacks overcome stereotypes of inferiority and prove their “manhood.” [55]Even so in many places in the army the USCT and state regiments made up of blacks were scorned:

“A young officer who left his place in a white regiment to become colonel of a colored regiment was frankly told by a staff officer that “we don’t want any nigger soldiers in the Army of the Potomac,” and his general took him aside to say: “I’m sorry to have you leave my command, and am still more sorry that you are going to serve with Negroes. I think that it is a disgrace to the army to make soldiers of them.” The general added that he felt this way because he was sure that colored soldiers just would not fight.” [56]

The general of course, was wrong, for “Nothing eradicated the prejudices of white soldiers as effectively as black soldiers performing well under fire. And nothing inspired black soldiers to fight as desperately as the fear that capture meant certain death.” [57] In the engagements where USCT units were allowed to fight, they did so with varying success most of which was often attributable to the direction of their senior officers and the training that they had received. As with any other unit, well led and well trained regiments performed better than those whose leaders had failed their soldiers. When given the chance they almost always fought well, even when badly commanded. This was true as well when they were thrown into hopeless situations.

One such instance was when Ferrero’s Division, comprised of colored troops were thrown into the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg when “that battle lost beyond all recall.” [58] The troops advanced in good order singing as they went, while their commander, General Ferrero took cover in a dugout and started drinking; but the Confederate defenders had been reinforced and “Unsupported, subjected to a galling fire from batteries on the flanks, and from infantry fire in front and partly on the flank,” a witness write, “they broke up in disorder and fell back into the crater.” [59] Pressed into the carnage of the crater where white troops from the three divisions already savaged by the fighting had taken cover, the “black troops fought with desperation, uncertain of their fate if captured.”[60] In the battle Ferrero’s division lost 1,327 of the approximately 4,000 men who made the attack. [61]

Major General Benjamin Butler railed to his wife in a letter against those who questioned the courage of African American soldiers seeing the gallantry of black troops assaulting the defenses of Petersburg in September 1864: The man who says that the negro will not fight is a coward….His soul is blacker than then dead faces of these dead negroes, upturned to heaven in solemn protest against him and his prejudices.” [62]

In another engagement, the 1864 Battle of Saltville in western Virginia the troops of the 5th USCT Cavalry who had been insulted, taunted, and derided by their fellow white Union soldiers went into action against Confederate troops defending the salt works in that town. The regiment’s commander, Colonel Wade, order his troops to attack. Colonel James Brisbin detailed the attack:

“the Negroes rushed upon the works with a yell and after a desperate struggle carried the line killing and wounding a large number of the enemy and capturing some prisoners…. Out of the four hundred men engaged, one hundred and fourteen men and four officers fell killed or wounded. Of this fight I can only say that men could not have behaved more bravely. I have seen white troops in twenty-seven battles and I never saw any fight better…. On the return of the forces those who had scoffed at the Colored Troops on the march out were silent.” [63]

The response of the Confederate government to Emancipation and African Americans serving as soldiers was immediate and uncompromisingly harsh. “When in the autumn of 1862 General Beauregard referred the question of a captured black soldier to Davis’s latest Secretary of War, James A. Seddon, the later replied “…my decision is that the negro is to be executed as an example.” [64] Davis approved of the summary executions of black prisoners carried out in South Carolina in November 1862, and a month later “on Christmas Eve, Davis issued a general order requiring all former slaves and their officers captured in arms to be delivered up to state officials for trial.” [65] Davis warned that “the army would consider black soldiers as “slaves captured in arms,” and therefore subject to execution.” [66] While the Confederacy never formally carried out the edict, there were numerous occasions where Confederate commanders and soldiers massacred captured African American soldiers.

The Lincoln administration responded to the Confederate threats by sending a note to Davis that threatened reprisals against Confederate troops if black soldiers suffered harm. It “was largely the threat of Union reprisals that thereafter gave African-American soldiers a modicum of humane treatment.” [67] Even so, they and their white officers were often in much more danger than the officers and soldiers of all-white regiments if captured by Confederate forces.

When captured by Confederates, black soldiers and their white officers received no quarter from many Confederate opponents. General Edmund Kirby Smith who held overall command of Confederate forces west of the Mississippi instructed General Richard Taylor to simply execute black soldiers and their white officers: “I hope…that your subordinates who may have been in command of capturing parties may have recognized the propriety of giving no quarter to armed negroes and their officers. In this way we may be relieved from a disagreeable dilemma.” [68] This was not only a local policy, but echoed at the highest levels of the Confederate government. In 1862 the Confederate government issued an order that threatened white officers commanding blacks: “any commissioned officer employed in the drilling, organizing or instructing slaves with their view to armed service in this war…as outlaws” would be “held in close confinement for execution as a felon.” [69] After the assault of the 54th Massachusetts at Fort Wagner a Georgia soldier “reported with satisfaction that the prisoners were “literally shot down while on their knees begging for quarter and mercy.” [70]

On April 12th 1864 at Fort Pillow, troops under the command of General Nathan Bedford Forrest massacred the bulk of over 231 Union most of them black as they tried to surrender. While it is fairly clear that Forrest did not order the massacre and even may have attempted to stop it, it was clear that he had lost control of his troops, and “the best evidence indicates that the “massacre”…was a genuine massacre.” [71] Forrest’s soldiers fought with the fury of men possessed by hatred of an enemy that they considered ‘a lesser race’ and slaughtered the Union troops as they either tried to surrender or flee; but while Forrest did not order the massacre, he certainly was not displeased with the result. His subordinate, General James Chalmers told an officer from the gunboat Silver Cloud that he and Forrest had neither ordered the massacre and had tried to stop their soldiers but that “the men of General Forrest’s command had such a hatred toward the armed negro that they could not be restrained from killing the negroes,” and he added, “it was nothing better than we could expect so long as we persisted in arming the negro.” [72] It was a portent of what some of the same men would do to defenseless blacks and whites sympathetic to them as members of the Ku Klux Klan, the White Liners, White League, and Red Shirts, during and after Reconstruction in places like Colfax Louisiana.

Ulysses Grant was infuriated and threatened reprisals against any Confederates conducting such activities, he a later wrote:

“These troops fought bravely, but were overpowered I will leave Forrest in his dispatches to tell what he did with them.

“The river was dyed,” he says, “with the blood of the slaughtered for up to 200 years. The approximate loss was upward of five hundred killed; but few of the officers escaped. My loss was about twenty killed. It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.” Subsequently Forrest made a report in which he left out the part that shocks humanity to read.” [73]

The bulk of the fanatical hatred of Forrest’s troops was directed at the black soldiers of the 6th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery, which composed over a third of the garrison. “Of the 262 Negro members of the garrison, only 58 – just over 20 percent – were marched away as prisoners; while of the 295 whites, 168 – just under sixty percent were taken.” [74] A white survivor of the 13th West Tennessee Cavalry, a Union unit at the fort wrote:

“We all threw down our arms and gave tokens of surrender, asking for quarter…but no quarter was given….I saw 4 white men and at least 25 negroes shot while begging for mercy….These were all soldiers. There were also 2 negro women and 3 little children standing within 25 steps of me, when a rebel stepped up to them and said, “Yes, God damn you, you thought you were free, did you?” and shot them all. They all fell but one child, when he knocked it in the head with the breech of his gun.” [75]

A Confederate Sergeant who was at Fort Pillow wrote home a week after the massacre: “the poor deluded negroes would run up to our men, fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands scream for mercy, but were ordered to their feet and shot down.” [76] The captain of the Union gunboat Silver Cloud was allowed by the Confederate to bring his ship to the Fort to evacuate wounded, and to bury the dead was appalled at the sight, he wrote:

“All the buildings around the fort and the tents and huts in the fort had been burned by the rebels, and among the embers of the charred remains of numbers of our soldiers who had suffered terrible death in the flames could be seen. All the wounded who had strength enough to speak agreed that after the fort was taken an indiscriminate slaughter of our troops was carried on by the enemy…. Around on every side horrible testimony to the truth of this statement could be seen, Bodies with gaping wounds,… some with skulls beaten through, others with hideous wounds as if their bowels had been ripped open with bowie-knives, plainly told that little quarter was shown…. Strewn from the fort to the river bank, in the ravines and the hollows, behind logs and under the brush where they had crept for protection from the assassins who pursued them, we found bodies bayoneted, beaten, and shot to death, showing how cold-blooded and persistent was the slaughter…. Of course, when a work is carried by assault there will always be more or less bloodshed, even when all resistance has ceased; but here there were unmistakable evidences of a massacre carried on long after any resistance could have been offered, with a cold-blooded barbarity and perseverance which nothing can palliate.” [77]

The rabidly pro-slavery members of the Confederate press lent their propaganda to cheer the massacre of the captured blacks. John R. Eakin of the Washington (Arkansas) Washington Telegraph, who later became a justice on the Arkansas Supreme Court after Reconstruction, wrote,

“The Slave Soldiers. – Amongst there are stupendous wrongs against humanity, shocking to the moral sense of the world, like Herod’s massacre of the Innocents, or the eve of St. Bartholomew, the crime of Lincoln in seducing our slaves into the ranks of his army will occupy a prominent position….

How should we treat our slaves arrayed under the banners of the invader, and marching to desolate our homes and firesides….

Meanwhile, the problem has been met our soldiers in the heat of battle, where there has been no time for discussion. They have cut the Gordian knot with the sword. They did right….

It follows that we cannot treat negroes in arms as prisoners of war without a destruction of the social system for which we contend. We must be firm, uncompromising and unfaltering. We must claim the full control of all negroes who may fall into our hands, to punish with death, or any other penalty, or remand them to their owners. If the enemy retaliate, we must do likewise; and if the black flag follows, the blood be upon their heads.” [78]

However, when African American Troops were victorious, and even after they had seen their brothers murdered by Confederate troops, that they often treated their Confederate with great kindness. Colonel Brisbin wrote that following Battle of Saltville that “Such of the Colored Soldiers who fell into the hands of the Enemy during the battle were murdered. The Negroes did not retaliate but treated the Rebel wounded with great kindness, carrying them water in their canteens and doing all they could to alleviate the sufferings of those whom the fortunes of war had placed in their hands.” [79]

Part Three coming soon.