Dear Readers and Friends,

Tonight I give you one of the biographical vignettes from my Gettysburg Staff Ride Text, which will one day be my Gettysburg trilogy. Unlike many texts about the battle, my account has these biographical vignettes woven through the story of the battle, as I believe that the stories of the men involved shaped the outcome of the battle, and in some cases the war and Reconstruction.

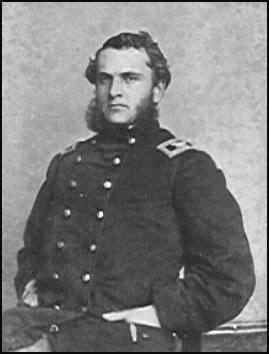

This section is about Colonel Strong Vincent, a brigade commander in Barnes’s division of the Union V Corps which played a large part in successfully defending Little Round Top on July 2nd 1863.

While Vincent is not as well known as Colonel Joshua Chamberlain, it was he who placed Chamberlain’s 20th Maine in its position at the end of the Federal line and led the defense of the hill until he was mortally wounded. He also was one of the more intuitive Union officers regarding the nature of the Confederacy and what was needed to end the rebellion. His thoughts on that were much like those of William Tecumseh Sherman. Likewise, he did not display the sentimental nature of Chamberlain. He was a realist. I hope that you enjoy. It has been too long since I have had the chance to do anything with this text.

Colonel Strong Vincent was a 26-year-old Harvard graduate and lawyer from Erie, Pennsylvania. He was born in Waterford and attended school in Erie. Growing up, he worked in his father’s iron foundry, where the work helped make him a man of great physical strength. He studied at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut and transferred to Harvard. There are various explanations for why he left Trinity, but the most interesting and probably the most credible is that during his sophomore year which was recorded by Trinity alumnus Charles F. Johnson who wrote that:

“He went calling on Miss Elizabeth Carter, a teacher at Miss Porter’s school in Farmington, ten miles west of Hartford. At some point a guard or watchman voiced a comment that impinged the lady’s virtue, and, as Johnson so aptly phrases it, Vincent “responded to the affront with the same gallantry and vigor that he was to display in the Civil War.” McCook’s account indicated that the man was repeatedly pummeled, which effectively rendered him unconscious.” [1]

Long after the war Dr. Edward Gallaudet, the president of Trinity responded to an enquiry of the circumstances leading to Vincent’s early departure from Trinity. Gallaudet responded to the request in a terse manner:

“Replying to yours of yesterday, I must say that I do not think it would be wise to make public the story I told of Strong Vincent’s escapade at Farmington & its consequences. Certainly not in the lifetime of Mrs. Vincent.” [2]

The incident resulted in Vincent leaving Trinity, and the next year he entered Harvard. Vincent graduated from Harvard in 1859, ranking 51st in a class of 92. However, he was not an outstanding student and “earned admonishments on his record for missing chapel and smoking in Harvard Yard.” [3]

Returning home he studied law with a prominent lawyer and within two years had passed the bar, and he was well respected in the community. When war came and the call went out for volunteers, Vincent enlisted in a 30 Day regiment, the Wayne Guards, as a private and then was appointed as a 1st Lieutenant and Adjutant of the regiment because of his academic and administrative acumen.

He married Elizabeth, the same woman whose virtue he had defended at Trinity that day. Vincent, like many young northerners, believed in the cause of the Union undivided, and he wrote his wife shortly after the regiment went to war on the Peninsula:

“Surely the right will prevail. If I live we will rejoice in our country’s success. If I fall, remember you have given your husband to the most righteous cause that ever widowed a woman.” [4]

When the Wayne Guards were disbanded at the end of their enlistment, Vincent helped to raise the 83rd Pennsylvania and was commissioned as a Lieutenant Colonel in it on September 14th, 1861. The young officer learned his trade well and was considered a “strict disciplinarian and master of drill.” [5] That being said one enlisted man remarked that “no officer in the army was more thoughtful and considerate of the health and comfort of his men.” [6] Vincent assumed command of the regiment when the commander was killed during the Seven Days in June of 1862 where he learned lessons that he would help impart to his fellow officers as well as subordinates, including Chamberlain. At Fredericksburg any doubters about the young officer’s courage and leadership ability were converted where they observed his poise “with sword in hand” he “stood erect in full view of the enemy’s artillery, and though the shot fell fast on all sides, he never wavered or once changed his position.” [7]

By the time of the Battle of Gettysburg, the 26 year old Vincent was the youngest brigade commander in the army. He was noted for his intelligence, leadership, military acumen and maturity. One friend wrote “As a general thing his companions were older than himself….Among his associates were men of the highest rank. He could adapt himself to all, could talk with the politician on questions of history, with a general officer on military evolutions, or with a sporting man on the relative merits of horses,-and all respected his opinion.” [8]

His promotion was well earned, following a bout with a combination of Malaria and Typhoid, the “Chickahominy Fever” which almost killed him; Vincent took command of the regiment after its commander was killed at Gaines Mill. He commanded the regiment at Fredericksburg and was promoted to command the 3rd Brigade after the Battle of Chancellorsville following the resignation of its commander, Colonel T.W.B. Stockton on May 18th 1863.

Vincent was offered the chance to serve as the Judge Advocate General of the Army of the Potomac by Joseph Hooker in the spring of 1863 after spending three months on court-martial duty. But Vincent refused the offer in so that he might remain in the fight commanding troops. [9] He told his friends “I enlisted to fight.” [10]

Vincent, like Chamberlain who admired him greatly had “become a kind of model of the citizen soldier.” [11] As a result of his experience in battle and the tenacity of the Confederate army, he became an advocate of the tactics that William Tecumseh Sherman would later employ during his march to the sea in 1864. He wrote his wife before Chancellorsville:

“We must fight them more vindictively, or we shall be foiled at every step. We must desolate the country as we pass through it and not leave a trace of a doubtful friend or foe behind us; make them believe that we are in earnest, terribly in earnest; that to break this band in twain is monstrous and impossible; that the life of every man, yea, of every weak woman or child in the entire South, is of no value whatever compared with the integrity of the Union.” [12]

Unlike most other brigade commanders, Vincent was still a Colonel, and he, like many others would in his place hoping for a General’s star. He remarked that his move to save Sickles’ command “will either bring me my stars, or finish my career as a soldier.” [13] On July first, Vincent, a native Pennsylvanian came to Hanover and learning that battle had been joined, ordered “the pipes and drums of the 83rd Pennsylvania to play his brigade through the town and ordered the regiments to uncover their flags again….” [14] As the brigade marched through the town, Vincent “reverently bared his head” and announced to his adjutant, “What death more glorious can any man desire than to die on the soil of old Pennsylvania fighting for that flag?” [15]

Vincent was known for his personal courage and a soldier of the 83rd Pennsylvania observed: “Vincent had a particular penchant for being in the lead….Whenever or wherever his brigade might be in a position to get ahead…, he was sure to be ahead.” [16] That courage and acumen to be in the right place at the right time was in evidence when he led his brigade into battle on that fateful July second.

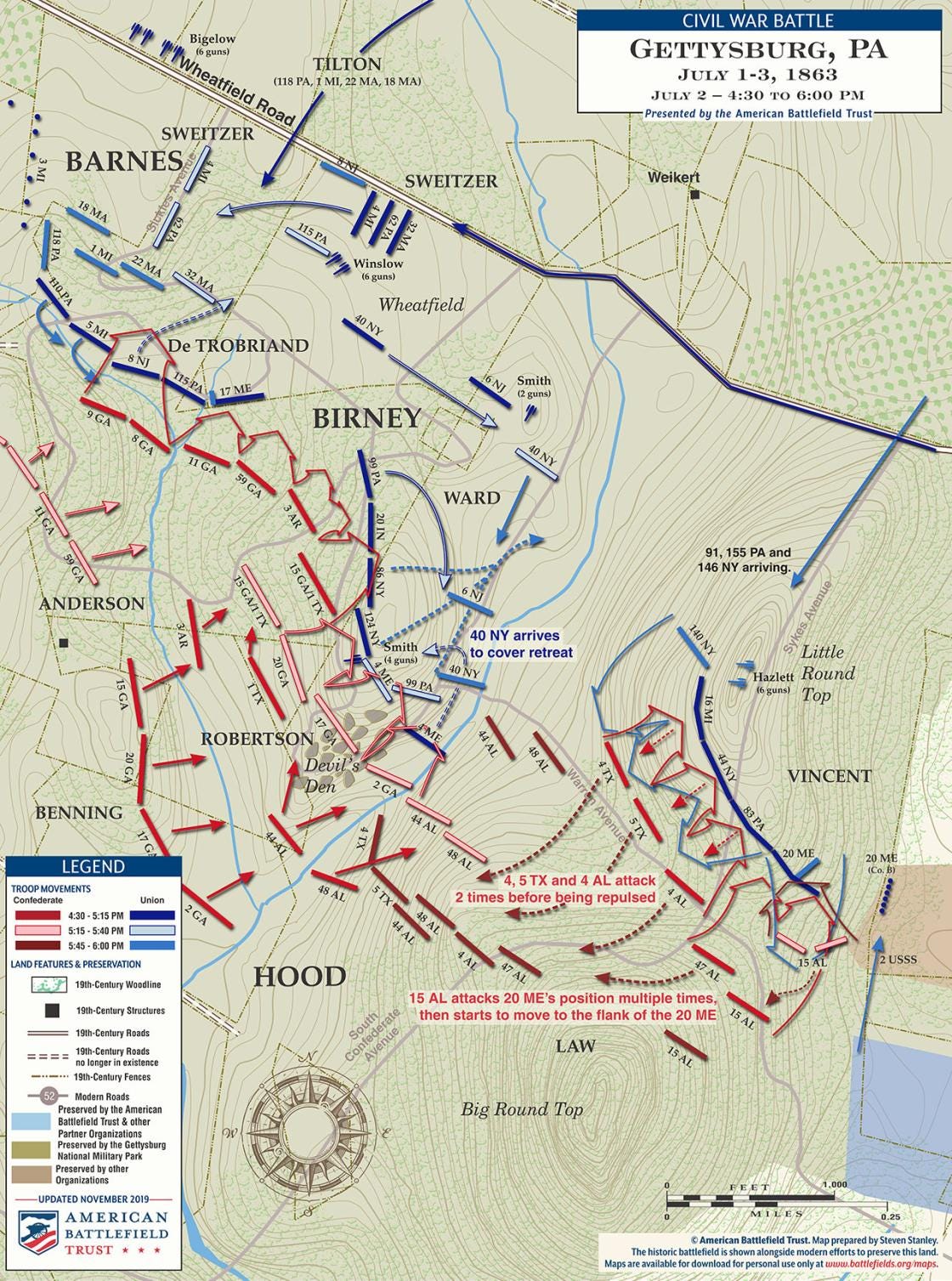

On July 2nd Barnes’ division of V Corps, which Vincent’s brigade was a part was being deployed to the threat posed by the Confederate attack of McLaws’ division on the Peach Orchard and the Wheat Field to reinforce Sickles’ III Corps. While that division marched toward the Peach Orchard, Vincent’s 3rd Brigade was the trailing unit. When Gouverneur Warren’s aide, Lieutenant Randall Mackenzie [17], approached the brigade in search of Barnes, he came across Vincent and his brigade near the George Weikert house on Cemetery Ridge, awaiting further orders. [18]

Vincent intercepted him and demanded what his orders were. Upon being told that Sykes’ orders to Barnes were to “send one of his brigades to occupy that hill yonder,” [19] Vincent defied normal protocol assuming that Barnes had hit the bottle and was drunk [20] and told Mackenzie “I will take responsibility of taking my brigade there.” [21] Vincent immediately went into action and ordered Colonel James Rice, his friend and the commander of the 44th New York “to bring the brigade to the hill as quickly as possible,” and then turned on his horse and galloped off toward Little Round Top.” [22]

It was a fortunate thing for the Union that he did. His quick action to get his brigade, clear orders to his subordinate commanders and skilled analysis of the ground were a decisive factor in the Union forces holding Little Round Top. After ordering Colonel Rice to lead the brigade up to the hill, he and his aide went forward to scout positions accompanied by the brigade standards. Rice brought the brigade forward at the double quick “across the field to the road leading up the north shoulder of the hill” with Chamberlain’s 20th Maine in the lead. [23]

Vincent and his orderly made a reconnaissance of the south and east slope of the hill which adjoined a small valley and a rocky outcrop called Devil’s Den, which was occupied by the 124th New York and which was the end of Sickles’ line. Near the summit of the southern aspect of the hill, they came under Confederate artillery fire and told his orderly “They are firing at the flag, go behind the rocks with it.” [24]

Vincent dismounted, leaving his sword secured on his horse, carrying only his riding crop. He continued and “with the skill and precision of a professional had reconnoitered and decided how to best place his slim brigade of 1350 muskets.” [25] He chose a position along a spur of the hill, which now bears his name, running from the northwest to the southeast to place his regiments where they could intercept the Confederate troops of Hood’s division which he could see advancing toward the hill.

What Vincent saw when he arrived was a scene of disaster. Confederate troops had overwhelmed the 124th New York and were moving on Little Round Top, “Devil’s Den was a smoking crater,” and the ravine which separated Devil’s Den from Little Round Top “was a whirling maelstrom.” [26] Seeing the threat Vincent began to deploy his brigade but also sent at messenger back to Barnes telling him “Go tell General Barnes to send reinforcements at once, the enemy are coming against us with an overwhelming force” [27]

The 16th Michigan, the smallest regiment in his brigade with barely 150 soldiers in line [28] was placed on the right flank of the brigade. As it moved forward, its adjutant, Rufus W. Jacklin’s horse was hit by a cannon ball which decapitated that unfortunate animal and left it “a mass of quivering flesh.” [29] A fierce Confederate artillery barrage fell among the advancing Union troops and splintered trees, causing some concern among the soldiers. The 20th Maine’s Chaplain, Luther French, saw the “beheading of Jacklin’s horse and ran to Captain Atherton W. Clark, commanding the 20th’s Company E, babbling about what he had seen. Clark interrupted French abruptly and shouted: “For Christ's sake Chaplain, if you have any business attend to it.” [30]

That section of the line was located on massive boulders that placed it high above the valley below, making it nearly impregnable to frontal attack. On the summit Vincent deployed the 83rd Pennsylvania and 44th New York to their left at the request of Rice who told him “In every battle that we have engaged the Eighty-third and Forty-fourth have fought side by side. I wish that it might be so today.” [31] The story is probably apocryphal but the regiments remained side by side with the 16th Michigan on the right and the 20th Maine on the left. The two regiments were deployed below the crest among the large number of boulders; the 83rd was about two-thirds of the way down the way down the slope where it joined the right of the 44th, whose line angled back up the slope to the southeast. A historian of the 83rd Pennsylvania noted that “Each rock”… “was a fortress behind which the soldier[s] instantly took shelter.” [32] The soldiers were determined to do their duty as they were now fighting on home ground.

Vincent deployed the 20th Maine on his extreme left of his line, and in fact the extreme end of the Union line. Vincent knew that if this flank was turned and Chamberlain overrun that it would imperil the entire Union position. Vincent came up to Chamberlain who remembered that Vincent said “in an awed, faraway voice: “I place you here….This is the left of the Union line. You understand. You are to hold this ground at all costs.” [33]

Vincent was wounded while leading the defense of the hill. As the men of Robertson’s Texas brigade rushed the hill and threatened to crack “the stout 16th Michigan defense…” [34] Vincent rushed to bolster the defenders. He was standing on a large boulder with a riding crop as the men of the 16th Michigan were beginning to waiver. Fully exposed to enemy fire he attempted to drive the retreating men back into the fight. Brandishing the riding which he cried out: “Don’t yield an inch now men or all is lost,” [35] and moments later was struck by a “minié ball which passed through his left groin and lodged in his left thigh. He fell to the ground, and as he was being carried from the field, “This is the fourth or fifth time they have shot at me…and they have hit me at last.” [36]

Mortally wounded, Vincent was taken to a field hospital at the Weikert farm where he lingered for five days before succumbing to his wounds. In the yard lay the body of Paddy O’Rorke whose regiment had saved his brigade’s right flank. Vincent knew that he was dying and he requested that a message be sent to Elizabeth for her to come to Gettysburg. It did not reach her in time. Though he suffered severe pain he bravely tried not to show it. Eventually he became so weak that he could no longer speak. “On July 7, a telegram from President Lincoln, commissioning Vincent a brigadier general, was read to him, but he could not acknowledge whether he understood that the president had promoted him for bravery in the line of duty.” [37] He died later that day and his body was transported home to Erie for burial. Ten weeks after his death his wife gave birth to a baby girl. The baby would not live a year and be buried next to him.

Colonel Rice, who led the 44th New York up the hill and took command of the brigade on Vincent’s death, memorialized his fallen commander in his general order to the brigade on July 12th:

“The colonel commanding hereby announces to the brigade the death of Brig. Gen. Strong Vincent. He died near Gettysburg, Pa., July 7, 1863, from the effects of a wound received on the 2d instant, and within sight of that field which his bravery had so greatly assisted to win. A day hallowed with all the glory of success is thus sombered by the sorrow of our loss. Wreaths of victory give way to chaplets of mourning, hearts exultant to feelings of grief. A soldier, a scholar, a friend, has fallen. For his country, struggling for its life, he willingly gave his own. Grateful for his services, the State which proudly claims him as her own will give him an honored grave and a costly monument, but he ever will remain buried in our hearts, and our love for his memory will outlast the stone which shall bear the inscription of his bravery, his virtues, and his patriotism.

While we deplore his death, and remember with sorrow our loss, let us emulate the example of his fidelity and patriotism, feeling that he lives but in vain who lives not for his God and his country.” [38]

Vincent’s wife Elizabeth never married again and was taken in by the Vincent family. Vincent’s younger brother became an Episcopal Priest and then was consecrated as a Bishop. He later provided a home for her. She became a tireless worker in the church working with charitable work for young women and children. This led to an interest in sacred art and she wrote two books: Mary, the Mother of Jesus and The Madonna in Legend and in Art. She also translated Delitzch’s Behold the Man and A Day in Capernaum from the German. [39] Elizabeth Vincent passed away in April 1914 and was buried beside her husband and daughter.

Notes:

[1] Nevins, James H. and Styple, What Death More Glorious: A Biography of General Strong Vincent Belle Grove Publishing Co, Kearny N.J. 1997 p.16

[2] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious p.17

[3] Ibid. LaFantasie, Glenn W. Twilight at Little Round Top: p.105

[4] ________. Erie County Historical Society http://www.eriecountyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/10/strongvincent.pdf retrieved 9 June 2014

[5] Golay, Michael. To Gettysburg and Beyond: The Parallel Lives of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Edward Porter Alexander Crown Publishers Inc. New York 1994 p.129

[6] Nevins, James H. and Styple, William B. What Death More Glorious: A Biography of General Strong Vincent Belle Grove Publishing Company, Kearney NJ 1997 p.29

[7] Ibid Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.262

[8] Ibid.Nevins, What Death More Glorious p.54

[9] Leonardi, Ron Strong Vincent at Gettysburg in the Barringer-Erie Times Newsretrieved June 9th 2014 from http://history.goerie.com/2013/06/30/strong-vincent-at-gettysburg/

[10] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious p.55

[11] Wallace, Willard. The Soul of the Lion: A Biography of Joshua L. Chamberlain Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg PA 1960 p.91

[12] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious p.57

[13] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.264

[14] Pfanz, Harry F. Gettysburg: The Second Day. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1987 p.51

[15] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage p.159

[16] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.305

[17] Some such as Guelzo believe this may have been Captain William Jay of Sykes staff

[18] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.327

[19] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage p.262

[20] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage p.262

[21] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.327

[22] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.108

[23] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.389

[24] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.109

[25] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.390

[26] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage p.270

[27] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious p.75

[28] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p.292

[29] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.109

[30] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.109

[31] Ibid. Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day. p.213

[32] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.111

[33] Ibid. Golay, To Gettysburg and Beyond p.157

[34] Ibid. Wallace The Soul of the Lion p.95

[35] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage p.272

[36] Ibid. Trudeau, Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage p.361

[37] Ibid. LaFantasie Twilight at Little Round Top p.207

[38] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious p.86

[39] Ibid. Nevins What Death More Glorious pp.87-88