Innovations of Death: The Minié Ball, the Rifled Musket, and the Repeating Rifle

Today I am sharing a section of my second, yet-to-be-published book about the immense impact of the American Civil War on America, and also the world. It was a revolutionary war in an age of great change. The changes included societal changes, innovations in military doctrine made necessary by technology and the scope of the war, and a shift from limited war to near-total war.

The book is quite expansive and deals with topics one typically finds in works that focus on narrow topics in a detailed manner, but none that I have seen approach this in the way that I will do. My work is very detailed and puts the information into one volume. It is interesting because the book began as the first of two introductory chapters to my Gettysburg Staff Ride Text, which I developed to teach my students while leading that expedition while on the faculty of the Joint Forces Staff College. The second chapter became my first book; Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: Religion and the Politics of Race in the Civil War Era and Beyond, which I urge everyone to purchase if you want to understand the roots of today’s White nationalism, Christian nationalism, and MAGA, as well as the roots of the Civil Rights movement. Professor Charles B. Dew, the author of Apostles of a Disunion: Southern Secession Commissioners and the Causes of the Civil War, calls it a “Book for our time.”

This article is part of a chapter on military weapons technology. The chapter is particularly important because it deals with the deadly development of the rifled musket and repeating rifle along with a type of ammunition that made the rifled musket far deadlier than previous weapons. I think that is important because the ammunition used by the rifled muskets was incompatible with the repeating rifles, especially the Winchester, introduced in 1866, too late for the war, found their way into civilian use to become one of the deadliest weapons in the hands of civilians until the AR-15 came along. Both were weapons of war which now in the hands of civilians became a scourge of our nation.

The fact that I have always been a military historian as well as a technology geek who has seen the impact of such weapons on human bodies, at war and in major U.S trauma centers, who has qualified or familiarized with every U.S. Army and Marine Corps personnel and Crew served weapon until 2014, which kind of makes me something of a subject matter expert who doesn’t think that weapons like the AR-15 belongs in civilian hands. The AR-15 was designed for one purpose and one purpose only, to kill enemy soldiers in large numbers as easily as possible. But I digress, here is that section of the chapter. It is a draft, more work is to be done, especially editing.

“Breechloaders and Greencoats” by Dale Gallon - The Second U.S. Sharpshooters at Gettysburg

While various individuals and manufacturers had been experimenting with rifles for some time, the weapons were difficult to load as the rifled groves slowed down the loading process. The British pioneered using the rifle during the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. They issued the Baker rifle, a rifled flintlock that was accurate to about 300 yards to a small number of elite Rifle Regiments, as well as skirmishers in some other regiments. The soldiers assigned to the Rifle regiments wore a distinctive green uniform as opposed to the red worn by the rest of the British Army.

When the United States Army formed its first Sharpshooter regiment in late 1861 under the command of Colonel Hiram Berdan, the soldiers of the regiment as well as the 2nd Regiment of Sharpshooters were issued modified breech-loading Sharps New Model 1859 Rifles, instead of the M1861 Springfield Rifled Musket. They wore a distinctive green uniform instead of the standard Union Blue. The units did not fight as a regiment but as company and even platoon sized detachments sent to when they were most needed. The Sharpshooter Regiments were highly selective, elite volunteer units. Berdan specified that “no man be accepted who cannot, at 200 yards, put 10 consecutive shots in a target, the average distance not to exceed five inches from the center of the bullseye.” [1] As the companies of the regiments trained their marksmen frequently could achieve the goal with three inches of the bullseye. The regiments fought in every major engagement in the Eastern Theater with the Army of the Potomac, and under 3,000 soldiers served in them during the war.

In 1832, Captain John Norton of the 34th Regiment of Foot in the British Army “invented a Cylindro-Conoidal bullet. When fired, its hollow base automatically expanded to engage the barrel's rifling, thus giving the bullet a horizontal spin.” [2] But the bullet was unwieldy. It and other bullets large enough to take the rifling were difficult to ram down the barrel of the weapon. The process slowed down the rate of fire significantly, and since “rapid and reliable firing was essential in a battle, the rifle was not practical for the mass of the infantrymen.” [3] The British Ordnance Bureau rejected it, leaving most British soldiers with older smoothbore muskets until the late 1850s.

The Minié Ball

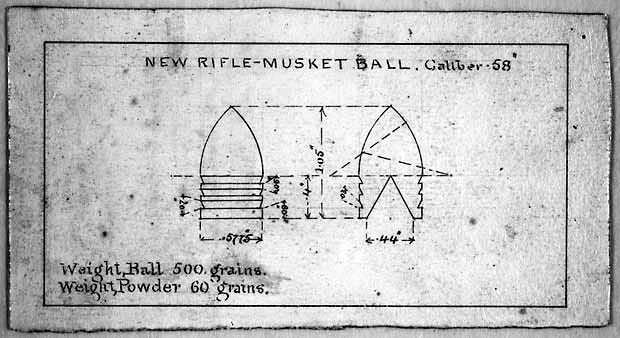

In 1848 French Army Captain Claude Minié “perfected a bullet small enough to be easily rammed down a rifled barrel, with a wooden plug in the base of the bullet to expand it upon firing to take the rifling.” [4] He also “placed a hollow indentation on the bottom surface of a cylindrical-conical bullet to allow the powder gases to expand the soft lead sides of the ball and fit the spiral grooves inside the barrel.” [5]

However, the bullets were expensive to produce, and it was not until 1850 that an American armorer at Harpers Ferry, James Burton, “simplified the design that had made Minié famous and developed a hollow based, .58-caliber lead projectile that could be cheaply mass-produced.” [6] Burton’s ammunition was very easy to load into weapons, and soldiers could drop the cartridge into the muzzle of their rifles as easily as musket balls could be down a smoothbore.

Claude Minié

Unfortunately, the tactics that officers were educated on were developed at a time when the maximum effective range of muskets was barely 100 yards, not the far greater range of rifled muskets. However, the U.S. Army made some minor adjustments to its tactics to increase speed and mobility in the tactical movement of the infantry. Colonel William J. Hardee, who became a Confederate General, adapted changes first made by the French to the U.S. infantry manual. These changes “introduced double-quick time (165 steps per minute) and the run and allowed changes to the order of march to be made in motion rather than after coming to a halt.” [7]

During the Napoleonic era assaulting an opponent with a large body of troops was a fairly easy proposition. One simply maneuvered out of the rage of the enemy’s artillery and muskets. It was possible “to bring a heavy mass of troops upon them was possible because of the limited destructiveness of smoothbore firearms. Their range was so restricted that defenders could count on getting off only one reasonably effective volley against advancing soldiers. By the time that volley was unloosed, the attackers would be so close to their objective that before the defenders could reload, the attacking troops would be upon them.” [8] One of Napoleon’s favorite tactics was for his troops to make well-executed turning maneuvers aimed at the enemy’s flanks, but the increased range and lethality of the rifled muskets used in the Civil War meant that even when such maneuvers were executed, they often produced only a short-term advantage as the defenders would form a new front and continue the action.

In 1860 rifled muskets had an effective range of about 500 yards or more based on the type of rifle as opposed to the barely 100-yard range of smoothbores. Nonetheless, most Civil War infantry engagements were fought at considerably shorter ranges. Paddy Griffith notes that even in the modern era, long-range firing by infantry units is still rare. He wrote there is “a fallacy in the notion that longer-range weapons automatically produce longer-range fire. The range of firing has much more to do with the range of visibility, the intentions of the firer and the general climate of the army.” [9]

Drew Gilpin Faust wrote that Civil War battles still “remained essentially intimate; soldiers were often able to see each other’s faces and to know who they had killed.” [10] Soldiers knew their weapons could fire at longer ranges, and one Union soldier explained, “When men can kill one another at six hundred yards, they would generally would prefer to do it at that distance.” [11] But such was the exception for most infantrymen during the war.

The advent of the breach loading and later, the repeating rifle and carbine further increased the firepower available to individual soldiers. However, except for the Prussian Army, armies in Europe and the United States Army were slow to adopt the breech-loading rifles. In “1841, the U.S. Arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, had prepared the pattern weapons of the first general-issue rifled shoulder arm of the U.S. Army” [12] However, the conversion process to the new weapons was slow as conservatism reigned in the Army, and the lack of suitable ammunition was a sticking point. While the U.S. Army began its conversion to the rifled musket in the 1840s, however, it “rejected both the repeating rifle and the breechloader for infantry because of mechanical problems.” [13]

Even so, there was continued resistance by leaders in the army to arming the infantry with the rifled muskets despite their already noted obsolescence during the Crimean War. In discussing the differences between rifles and smoothbore muskets during the Peninsular Campaign, Edward Porter Alexander wrote that “The Mexican War [was] fought with smooth bore, short-range muskets the character of the ground cut comparatively little figure. But with the rifled muskets & cannon of this war, the affair was proven both at Malvern Hill, & at Gettysburg….” [14]

In 1855 the new Secretary of War, and future President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, ordered the Army to convert to “the .58 caliber Springfield Rifled Musket. Along with the similar British Enfield rifle (caliber .577, which would take the same bullet as the Springfield), the Springfield became the main infantry arm of the Civil War.” [15] Despite this, the production of the new rifles was slow, and at the beginning of the war, only about 35,000 of all types were in Federal arsenals or the hands of Federal troops.

Though the production of the Springfield rifles and importation of Enfields soon made up for their scarcity at the beginning of the war, the conversion to breech-loading weapons took more time. Union Chief of Ordnance Brigadier General James W. Ripley was mistaken in his “insistence in sticking by the muzzle-loading rifle as the standard infantry arm, rather than introducing the breach-loading repeating rifle.” [16] Ripley believed that a “move to rapid fire repeating rifles would put too much stress on the federal arsenals’ ability to supply the repeaters in sufficient quantities for the Union armies.”[17] His refusal to produce breech loaders led to his forced removal as head of the Bureau in September 1863. There is a measure of truth in Ripley’s recalcitrance, for troops armed with these weapons did tend to waste significantly more ammunition than those armed with slow-firing muzzleloaders, but had he done so, the war may not have lasted nearly as long. Ripley’s successor, Brigadier General Alexander Dyer built upon the foundation established by Ripley. He was much more technologically inclined and based in the Union Cavalry’s success with breech-loaders Dyer urged their rapid issue to the Union Infantry. [18]

Had Ripley done this, Union infantry would have enjoyed an immense superiority in sheer weight of firepower on the battlefield. The noted Confederate artilleryman and post-war analyst Porter Alexander believed that had the Federals adopted breech-loading weapons, the war would have been over very quickly, stating, “There is reason to believe that had the Federal infantry been armed from the first with even the breech-loaders available in 1861 the war would have been terminated within a year.” [19] Alexander’s observation is quite correct. As the war progressed and more Union troops were armed with breach-loaders and repeaters, the Confederates could not stand up to the vastly increased firepower of Union units armed with the newer weapons. A Union soldier assigned to the 100th Indiana of Sherman’s army in 1865:

“I think the Johnnys are getting rattled; they are afraid of our repeating rifles. They say that we are not fair, that we have guns that we load up on Sunday and shoot all the rest of the week. This I know. I feel a good deal confidence in myself with a 16 shooter in my hands than I used to with a single-shot rifle.” [29]

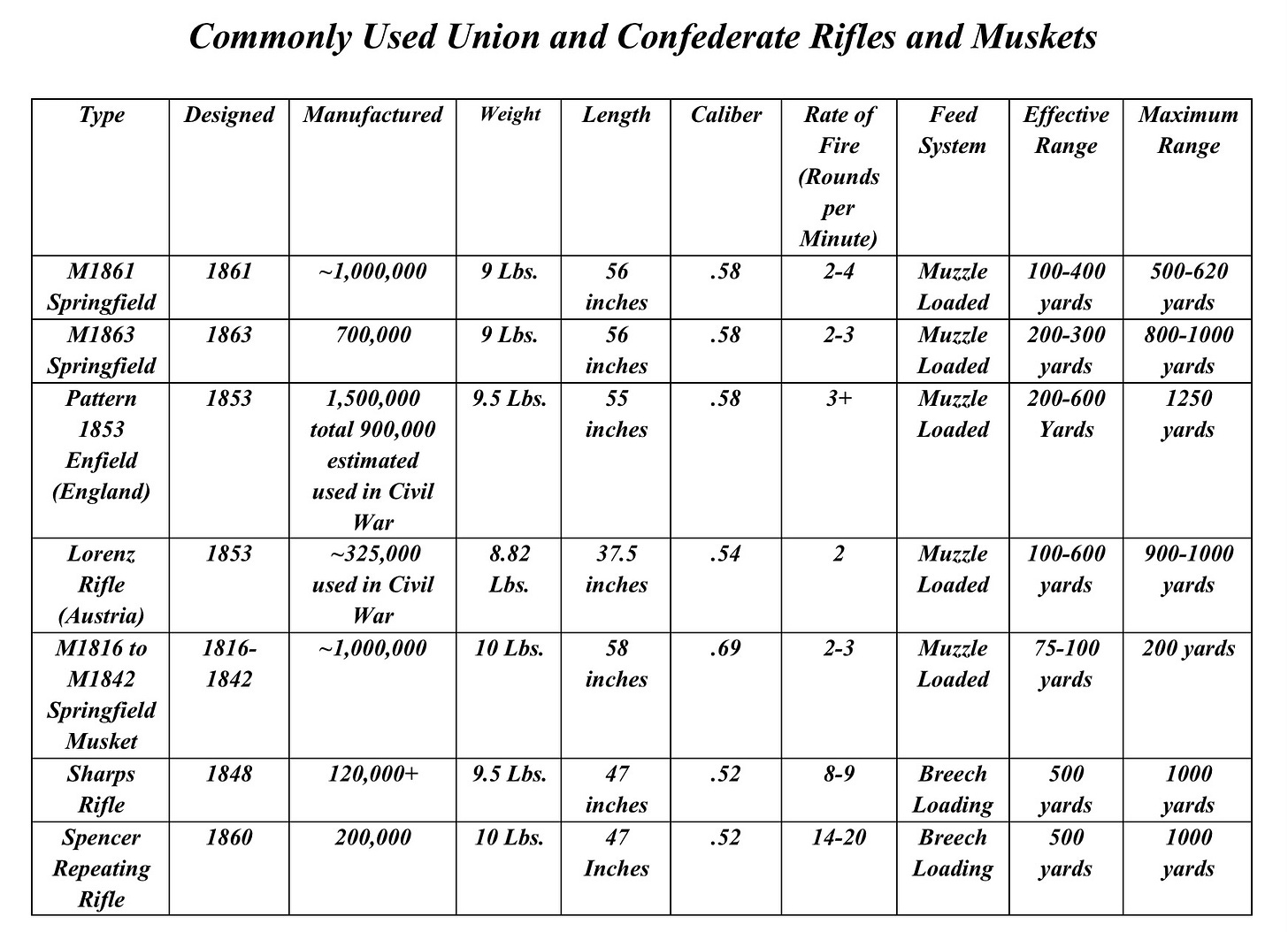

During the war, both the Union and Confederate armies used a large number of shoulder-fired rifles and muskets of various manufactures and vintage. The situation was due to a shortage of the standard M1861 Springfield Rifled Musket at the beginning of the war. As a result, standardization was a problem, and many units went to war armed with various weapons, making supply, training, and coordinated fires in battle difficult. At the beginning of the war, the Federal government had only about 437,000 muskets and rifles in its inventory, and only 35,000 were rifled muskets, either older weapons converted from smoothbores or the newly manufactured Springfield rifles.

The disparity of types of weapons that might be found in a single regiment contributed to difficulties in supplying ammunition to them. It proved to be nightmarish for experienced quartermasters and even more so for the amateur quartermasters of many units who did not specify exactly what types of ammunition they required.

In addition to the small number of existing weapons stocks available, the Federal government only had two armories capable of manufacturing arms. The most important was at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. It had to be abandoned in 1861 when Virginia seceded from the Union and was not secured until after the Battle of Antietam in October 1862. Until it was secured, only Springfield, Massachusetts, remained. It could manufacture between 3,000 and 4,000 rifles a month. Ordnance Chief Ripley solved that problem by contracting with the United States and foreign manufacturers to make up for what government armories could not do. In the first year of the war, he acquired nearly 750,000 rifles from U.S. and foreign arms suppliers. Ripley expanded Springfield’s capacity to produce over 300,000 weapons a year. Even so, at Gettysburg, sixty-five of the 242 or 26% of Union infantry regiments were fully or partially armed with older substandard smoothbores and antiquated rifles. In 1863 and 1864, over half of the Confederate Army of the Tennessee was armed with smoothbores or antiquated rifles. [21]

The initial shortage of weapons caused problems for both sides. The Confederacy had to make the best use of what they captured from federal depots at the beginning of the war, which amounted to 140,000 smoothbores and another 35,000 rifled muskets. Unlike the Federal Government, the Confederacy had much less industrial capacity and was forced to purchase many of its weapons from England. The Confederates were forced to spend badly needed capital, and the weapons had to be shipped through the Union blockade on blockade runners operating from England, the Bahamas, or other English Caribbean possessions. During the war, the Confederates purchased approximately 300,000 rifled muskets and 30,000 smoothbores from Europe while producing just over 100,000 shoulder-fired weapons. Because of its economic and industrial superiority, the Union acquired a million rifled muskets and 100,000 smoothbores from Europe in addition to the 1.75 million rifled muskets, 300,000 breechloaders, and 100,000 repeaters of its wartime manufacture. [22]

Ultimately, the disparity in quality and quantity of arms would doom the élan of the Confederate infantry in battle after battle. Porter Alexander wrote of the Confederate equipment situation:

“The old smooth-bore musket, caliber 69, made up the bulk of the Confederate armament at the beginning, some of the guns, even all through 1862, being old flint-locks. But every effort was made to replace them by rifled muskets captured in battle, brought through the blockade from Europe, or manufactured at a few small arsenals which we gradually fitted up. Not until after the battle of Gettysburg was the whole army in Virginia equipped with the rifled musket. In 1864 we captured some Spencer breech-loaders, but we could never use them for lack of proper cartridges.” [23]

The number of kinds of weapons that a given unit might be equipped was difficult for commanders and logisticians on both sides. For example, Sherman’s division at the Battle of Shiloh “utilized six different kinds of shoulder arms, with each necessitating a different caliber of ammunition,” [24] which caused no end of logistical problems for Sherman’s troops as well as other units equipped with mixed ordnance.

While the increase in range, accuracy, and rate of fire were important, they were also mitigated by other factors. First, the smoke created by the black, non-smokeless gunpowder powder expended by all weapons during the Civil War often obscured the battlefield. Likewise, the stress of combat reduced the rate and accuracy of fire of the typical soldier.

These were compounded by the fact that most soldiers received little real marksmanship training. This was compounded by the fact that the “Minié ball traced a curved trajectory, sailing upward in a high arc before descending to the ground.” The trajectory meant that if the soldier sighted his weapon to 300 yards and did not compensate for it that the bullet would likely fly over the heads of closer targets. [25] As with all things in war, training is everything, and despite the pleas of men like 1st Lieutenant Cadmus Wilcox who studied the physics of bullets fired by rifled muskets, the Army did not establish a training course on rifle instruction before the war, and instead “It encouraged subordinate officers to give rifle practice to their men but failed to provide funds to purchase ammunition.” [26]

Allen Guelzo notes that the “raw inexperience of Civil War officers, the poor training in firearms offered to the Civil War recruit, and the obstacles created by the American terrain generally cut down the effective range of Civil War combat to little more than eighty yards.” [27] That being said, trained soldiers learned to adjust to the curved trajectory to hit individual targets at long range, while well-drilled regiments engaging enemy troops in the open on the ground of their choosing could deliver devastating volley fire on their enemies.

But the real increase in lethality on the Civil War battlefield was the Minié ball “which could penetrate six inches of pine board at 500 yards.” [27] As such, the bullet was decidedly more lethal than the old smoothbore rounds, and most wounds “were inflicted by Minié balls fired from rifles: 94 percent of Union casualties were caused by bullets.” [28] The old musket balls were fired at a comparatively low velocity and when they hit a man they often passed through a human body nearly intact, unless there was a direct hit on a bone. Thus wounds were generally fairly simple to treat unless a major organ or blood vessel had been hit. But the Minié ball ushered in for those hit by it as well as the surgeons who had to treat their wounds:

“The very attributes that increased the bullet’s range also increased its destructive potential when it hit its target. Unlike the solid ball, which could pass through a body nearly intact, leaving an exit would not much larger than the entrance wound, the soft, hollow-based Minié ball flattened and deformed on impact, while creating a shock wave that emanated outward. The Minié ball didn’t just break bones, it shattered them. It didn’t just pierce organs, it shredded them. And if the ragged, tumbling bullet had enough force to cleave completely through the body, which it often did, it tore out an exit wound several times the size of the entrance wound.” [29]

When these bullets hit the arm and leg bones of soldiers the effects were often catastrophic and required immediate amputation of the limb by surgeons working in abysmal conditions. “The two minie bullets, for example, that struck John Bell Hood’s leg at Chickamauga destroyed 5 inches of his upper thigh bone. This left surgeons no choice but to amputate shattered limbs. Hood’s leg was removed only 4 and 1/2 inches away from his body. Hip amputations, like Hood’s, had mortality rates of around 83%.” [30]

Brett Gibbons wrote that the Rifle-Musket “shattered Napoleonic convention almost overnight; prescient theorists and tacticians realized dense columns and close-order battle lines were relics of the smoothbore age.” [31]

The technology that increased the range and lethality of infantry weapons changed the balance and gave armies fighting on the defensive an edge. The advance in the range and killing power embodied in the rifled musket made it especially difficult for the armies that fought the Civil War to successfully execute frontal assaults on prepared defenders. The defensive power was so enhanced that even well-executed turning maneuvers which were common and often decisive in the Napoleonic Era, were often repulsed. [32] Well-trained units could change their front against enemies assailing their flanks and turning them back as was demonstrated by Joshua Chamberlain’s 20th Maine at Little Round Top. Occasionally some assaulting troops would get in among the enemy’s lines, despite the enormous costs that they incurred during their attacks. However, the greater problem was how to stay there and exploit their advantage once they pierced the enemy’s line. Almost invariably, by that time the attacker had lost so heavily, and his reserves were distant, that he could not hold on against a counterattack by the defending army’s nearby reserves.” [33]

Despite the increased range of the rifled muskets many infantry firefights were still fought at closer ranges, usually under 200 yards, not much more than the Napoleonic era. Much of this had to do with the training of the infantry as well as visibility on the battlefield which in North America was often obscured by heavy forested areas and thickets in which armies would battle each other at close range. Battles such as the Seven Days, Chancellorsville, and much of the Overland Campaign were fought in such terrain.

The advantage of fighting on the defense was demonstrated throughout the course of the war as commanders attempted frontal assaults on such positions. “The only way to impose heavy enough casualties upon an enemy army to approximate that army’s destruction was to accept such heavy casualties oneself that no decisive advantage could accrue.” [34] Lee’s assault on Malvern Hill and his numerous frontal assaults on prepared positions at Gettysburg, Burnside’s futile assaults at Fredericksburg, Grant’s first attack at Vicksburg, and his ill-advised attack at Cold Harbor demonstrated the futility and ghastly cost of such tactics. The ability of infantry in the assault to “rise up and deliver a frontal attack became almost always futile against any reasonably steady defenders. Even well executed flank attacks tended to suffer such heavy casualties as experienced riflemen maneuvered to form new fronts against them that they lost the decisiveness they had enjoyed in the Napoleonic Wars.” [35] During the Wilderness Campaign battles were fought for hours on end at point-blank range amid heavy woods and fortifications.

As important as the rifled muskets were, the real revolution in battlefield firepower was brought about by the repeating rifles and carbines which were introduced during the war. The paper cartridge ammunition used in early models made them dangerous to use. The cartridges sometimes caused gas and flames to escape from the breach, making the weapon dangerous to the user. But this was corrected with the introduction of brass cartridges, and later weapons became deadly instruments. Because of its range as compared to the older smoothbores, the rifled musket “added a new spatial dimension to the battlefield,” [36] but the repeating rifles, which had a shorter range than the rifled muskets looked forward to the day of semi-automatic and automatic weapons. The repeaters could “pump out so many shots in such a short time that it offered a new perspective in tactical theory from that used by the old carefully aimed one-shot weapons,” and added “a new temporal dimension to the close-range volley.” [37]

Despite the fact that leaders knew about the increased range and accuracy of rifled muskets, tactics in all arms of service were slow to change, and “on every occasion, a frontal assault delivered against an unshaken enemy led to failure.” [38] At Gettysburg Robert E. Lee demonstrated that he had not fully appreciated the effects of the lethality of the rifled musket when he ordered Hood’s assault on Federal troops at Little Round Top on July 2nd, and Pickett’s assault on the Union center on Cemetery Ridge the following day. Lee failed to learn the lessons of the bloody battles of 1862 and early 1863 which cost his army over 50,000 casualties, with deadly results.

But the lessons of the American Civil War were not absorbed by the European armies that went to war in 1914. In addition to the repeating rifles, new bolt action rifles could fire quickly and accurately at longer ranges than the rifled muskets of the Civil War, and machine guns were now part of infantry units of every nation. The results were even more ghastly.

Many historians debate whether due to the limitations in training and terrain of the American Civil War, and the rapid obsolescence of it after 1865 when it was replaced by breech-loaders in all armies, if it was a transformative weapon. Gibbons notes that the rifled musket, be it the British Enfield or American Springfield, was a rifle which through the rifling which gave the bullet its spin allowing it to hit targets more accurately at a greater distance made it the first modern rifle.

All modern infantry weapons like the M-16 use the same kind of grooved rifling developed in the 1840s and 1850s for their range and accuracy, where an unrifled M-16 would not be effective as would modern infantry tactics. Gibbons writes:

“Because rifling grooves allow for accurate shooting, the soldier can aim his weapon – be it a P1853 Enfield rifle-musket or an M4 automatic carbine – and individually engage targets out to several hundred yards. To effectively use such a weapon of precision, soldiers must be specifically trained in their use. The rifle-musket meets all these criteria, while the preceding weapon type, the smoothbore musket, does not.” [39]

Notes

[1] Stevens, C.A. Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac. 1892, copyright Big Byte Books, 2014

[2] Hagerman, Edward. The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare Midland Book Editions, Indiana University Press. Bloomington, IN. 1992 p.15

[3] McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 1988 p.474

[4] McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.474

[5] Hess, Earl J. Civil War Infantry Tactics: Training, Combat, and Small-Unit Effectiveness, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, LA, 2015 Amazon Kindle Edition, loc. 878

[6] Leonard, Pat The Bullet that Changed History in The New York Times Disunion: 106 Articles from the New York Times Opinionator edited by Ted Widmer with Clay Risen and George Kalogerakis, Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers, New York 2013 p.372

[7] Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.20

[8] Weigley, Russell F. A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History 1861-1865 Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 2000 p.33

[9] Griffith, Paddy, Battle Tactics of the Civil War Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1989 p.148

[10] Faust, Drew Gilpin, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War Vintage Books, a division of Random House, New York 2008 p.41

[11] Faust This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War p.41

[12] Weigley A Great Civil War p.32

[13] Hagerman The American Civil War and the Origins of Modern Warfare p.17

[14] Alexander Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander p.111

[15] McPherson. The Battle Cry of Freedom p.474

[16] Guelzo Allen C. Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War Era and Reconstruction Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2012 p.317

[17] Guelzo Fateful Lightning p.251

[18] Hattaway, Herman & Jones, Archer. How the North Won the Civil War, A Military History of the Civil War, University of Illinois Press, Champagne, IL. 1983 & 1991. p.140

[19] Alexander, Edward Porter Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative 1907 republished 2013 by Pickle Partners Publishing, Amazon Kindle Edition location 1691 of 12969

[20] Davis, Burke. Sherman’s March Open Roads Integrated Media, New York, 2016, originally published by Vintage Press 1980 p.196

[21] Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War pp.76-77

[22] Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.80

[23] Alexander Military Memoirs of a Confederate location 1683 of 12969

[24] McDonough William Tecumseh Sherman: In the Service of My Country, A Life p.2

[25] Hess, Civil War Infantry Tactics: Training, Combat, and Small-Unit Effectiveness, loc. 902

[26] Hess, Civil War Infantry Tactics: Training, Combat, and Small-Unit Effectiveness, loc. 912

[26] Guelzo Fateful Lightening pp.255-256

[27] Guelzo Fateful Lightening p.250

[28] Faust This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War p.41

[29] Leonard, Pat The Bullet that Changed History p.372

[30] Goellnitz, Jenny Civil War Battlefield Surgery The Ohio State University, Department of History retrieved from https://ehistory.osu.edu/exhibitions/cwsurgeon/cwsurgeon/amputations 22 December 2016

[31] Gibbons, Brett. The Destroying Angel: The Rifle-Musket as the First Modern Infantry Weapon. 2019. p.5

[32] Weigley A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History 1861-1865 p.34

[33] Weigley, Russell F. The American Way of War: A History of United States Military History and Policy University of Indiana Press, Bloomington IN, 1973 p.117

[34] Weigley A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History 1861-1865 p.34

[35] Weigley, American Strategy from Its Beginnings through the First World War In Makers of Modern Strategy, from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age p.419

[36] Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.75

[37] Griffith, Battle Tactics of the Civil War p.75

[38] Fuller, J.F.C. The Conduct of War 1789-1961 Da Capo Press, New York 1992. Originally published by Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick N.J. p.104

[39] Gibbons The Destroying Angel: The Rifle-Musket as the First Modern Infantry Weapon. p.4