Note to readers. Some email providers will truncate this post as it exceeds their email limit. However, you can click the button to “read the entire article,” and it will appear in your email app or browser. You may also go to the website link, where you can also read it in its entirety.

Today I am presenting another section of a rather long chapter of my Gettysburg Staff Ride Text, and it tells the story of the climactic battle of the day. The general public knows it less than the Battle of Little Round Top, which is famous and dramatically portrayed in the film Gettysburg. The battles of July Second, 1863, at Gettysburg, were among the bloodiest and most complex, and most confusing of the Civil War. The battle began with Robert E. Lee ignored the advice of his First Corps Commander, Lieutenant General James Longstreet, to move the army around the left flank of the line of the Army of the Potomac to force it to abandon its positions to attack the Confederate army and instead launch an attack against the Federal line on Cemetery Ridge with the intent to turn its flank and destroy it with offensive action.

The fight began with an assault by Major General John Bell Hood’s Texas Division on the extreme Federal left at Devil's Den. It proceeded against the hastily occupied but well-defended Little Round Top and slowly developed against the Stoney Ridge, Rose’s Woods, the Wheat Field, and finally the Peach Orchard where the Division of Major General Lafayette McLaws came close to breaking the Union center.

The accounts of individual bravery, courage, and sacrifice on both sides in the midst of such a storm of metal is nearly unimaginable. Likewise, the examples of excellent and poor leadership and decision-making are quite pronounced, especially that of Robert E. Lee, who once he began the fight never got close enough to observe the damage to his forces, while George Meade and his lieutenants Winfield Scott Hancock and Gouverneur Warren were all over the battlefield making critical decisions that decided the day’s battle in favor of the Union. While July Third with the futile and disastrous attack known as Pickett’s Charge is considered by many as the turning point of the war, the fact is that the best chance for Confederate victory died at Plum Run on the evening of July Second.

This is the story of that last best chance and the men who stopped it, ensuring that the Confederacy would be defeated and slavery ended.

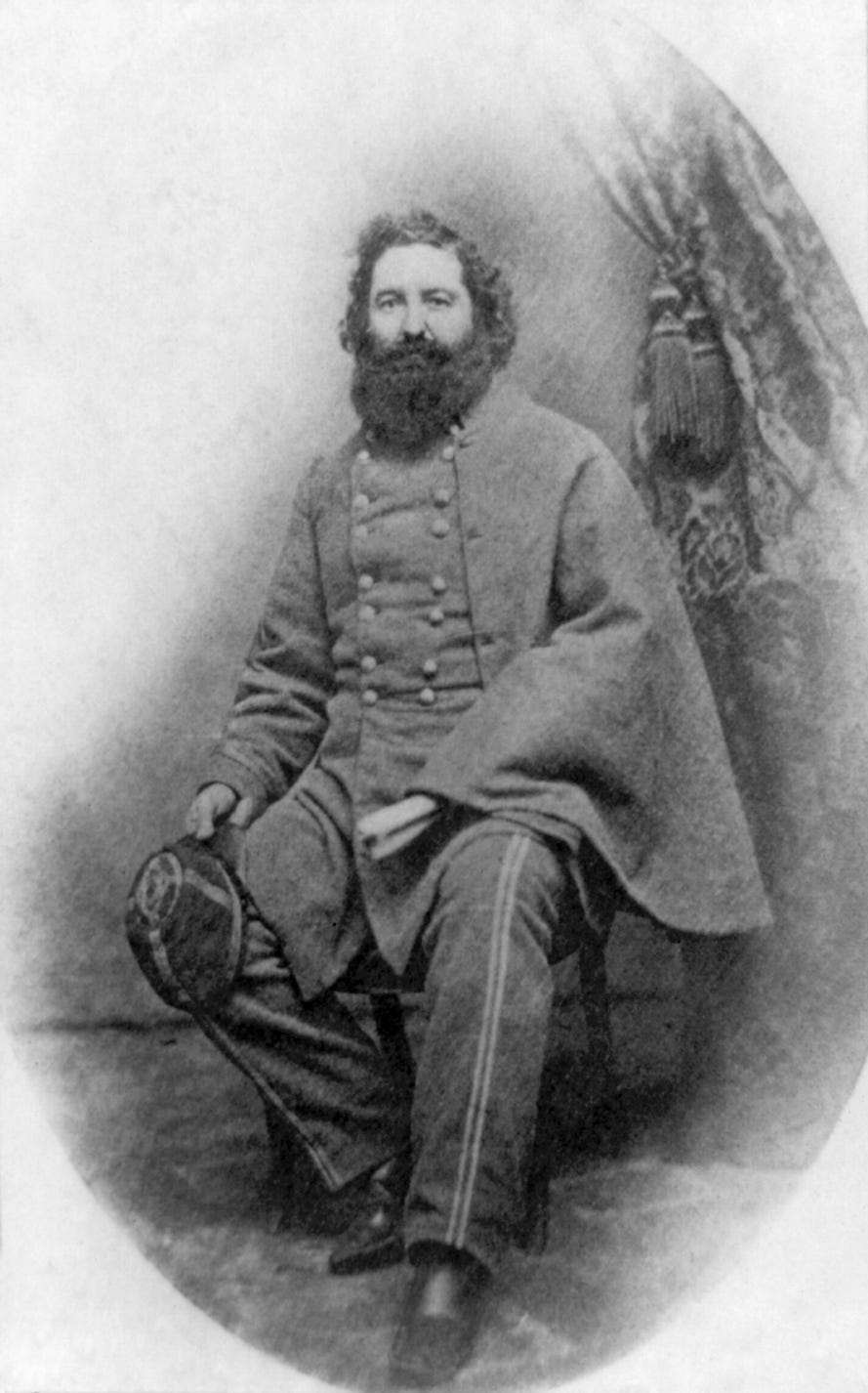

Major General Lafayette McLaws

It was now time for Longstreet to commit the last brigades of McLaws’ division, the Georgians of William Wofford and the Mississippians of William Barksdale. These units had been waiting west of the Peach Orchard as Hood’s attack developed, and the delay of Barksdale’s brigade getting into the fight had greatly chagrinned Joseph Kershaw when his South Carolinians made their attack without the Mississippi brigade supporting their left. “Longstreet never fully explained how he timed his order for Barksdale’s advance, nor did he specify why he allowed Kershaw to attack without Barksdale’s support.” [1] However, the delay was not easy on McLaws, or his brigade commanders, “particularly William Barksdale, whose thirst for glory was as sharp in Pennsylvania as it had been on his great day at Fredericksburg, where Lee, to his delight, had let him challenge the entire Yankee army.” [2] During the seemingly endless wait, the aggressive Barksdale plead with both McLaws and Longstreet to be allowed to attack, telling Longstreet, “I wish you would let me go in General!” “Wait a little,” answered Longstreet, “we are all going in presently.” [3] In the acrimonious post-war feud between the Confederate generals, Longstreet blamed McLaws for the delay. Mclaws blamed Alexander’s slowness in bringing up his artillery. Alexander complained of “four partial attacks of two brigades each [in Hood and McLaw’s divisions], requiring each an hour and a half to be gotten into action; where one advance by the eight brigades would have won a quicker victory with far less loss.” [4]

However, McLaws was now ready, and Longstreet gave the order to attack. Porter Alexander’s massed artillery opened the battle for the Peach Orchard, opening fire on the Federal troops with fifty-four guns drawn up to within five hundred yards of the Federal position. The Union Artillery chief, Brigadier General Henry Hunt, saw the Confederate build-up and brought up more artillery. By four o’clock, his artillery went “into battery not a minute too soon, the Rebel artillery that Hunt had spied moving into position let loose with a converging fire” [5] against Sickles’ exposed troops. The Confederate artilleryman “hoped, with my 54 guns & close range, to make it short, sharp, and decisive. At close ranges, there was less inequality in our guns, & especially in our ammunition, & I thought if I could ever overwhelm & crush them, I would do it now.” [6]

The effect of the barrage was dramatic as the Confederate guns blasted away at the men of Graham’s brigade of Birney’s division who held the angle of the Federal salient. Even so, Henry Hunt had managed to get “an impressive array of ordnance totaling thirty-two guns ready to take on the looming Confederate attack.” [7] By the time McLaws’s infantry attacked, “the three batteries in the Peach Orchard area had been increased to seven. A virtual solid line of forty Federal guns extended south from the Sherfy house to the Peach Orchard and east from there along the Wheatfield Road to Trostle’s Woods and the stony hill.” [8] Exposed to the massed fire of Alexander’s batteries, the Federal artillery replied furiously and with more effects than Alexander or the other Confederate commanders expected. Alexander recalled that “they really surprised me, both in the number of guns that they developed, & the way they stuck to them. I don’t think that there ever in our war a hotter, harder, sharper artillery afternoon than this.” [9] In the artillery slugfest, Alexander reported losing 144 men and 116 horses to the Federal batteries. He wrote, “So accurate was the enemy’s fire, that two of my guns were fairly dismounted, and the loss of men so great that I had to ask General Barksdale, whose brigade was lying down close to the wood, for help to handle the heavy 24-pounder howitzers of Moody’s battery.” [10] He noted that it was a higher toll than the artillery had suffered at Antietam during the entire battle. Henry Hunt’s gunners tenaciously held on to their exposed positions and with “waves of gray rolling all around them, some of the batteries in the forefront of the line went under, sucked into the vortex of death and devastation. Yet despite the opposition and the ninety-two-degree heat…other batteries held one stubbornly, hurling single and double charges of canister at their opponents, determined to seal up the holes in Meade’s line created by Dan Sickles’s impetuosity.” [11]

Leading the assault now was the battle-hardened Mississippi brigade of Brigadier General William Barksdale, a former congressional colleague of Sickles whose time in Congress was not without a journey or two into infamy. Barksdale was born in Smyrna, Tennessee, in 1822. He was a Mississippi lawyer, newspaper editor, and politician. Barksdale served in Mexico as a quartermaster officer of a militia unit, but though he was an administrator, he did not shy away from a fight. He “frequently appeared at the front during heavy fighting, often coatless and carrying a large sword.” [12]

While most of the former Regular Army Confederate officers supported and defended the institution of slavery and secession, many were less than passionate about either. They would have preferred that the Union had been preserved. However, Barksdale was one of the few generals serving in Lee’s Army who, in the decade leading up to the war, had become “violently pro-slavery and secessionist.” [13] But his views regarding secession had evolved since he had first entered politics. When Barksdale entered Mississippi politics, he was not a proponent of secession. He was solidly against it and, in one debate, remarked that “no occasion for the right of [secession] existed. [14] However, over time he became a reluctant supporter of secession and eventually “came to passionately embrace the Southern dream of an independent nation.” [15]

Barksdale was a passionate and sometimes violent man. As a state legislator and Congressman Barksdale was involved in a number of violent altercations with political opponents. In an 1853 incident at Vicksburg, he was attacked and stabbed several times before knocking his assailant, his former commander, during the War with Mexico out with one punch.

However, the incident for which Barksdale became most famous was an altercation that occurred when Representative Preston Brooks nearly killed Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner in the Senate chamber. During that brawl, Representative Elihu Washburne of Illinois landed a blow on Barksdale that sent Barksdale and his previously unsuspected wig flying. Someone snatched the wig from the floor and “waved it about like a captured flag.” When Barksdale finally recaptured the hairpiece he “plopped it on his head wrong side out, the absurdity of the scene giving the combatants pause.” [16] As the scrum broke up Barksdale was left “sputtering about his shame.” [17]

At the outbreak of the war Barksdale volunteered for service and enlisted as a private. Shortly thereafter he was elected Colonel of the 13th Mississippi Infantry Regiment. Barksdale took command of the Mississippi Brigade during the Seven Days Battles at Malvern Hill, and he was promoted to Brigadier General in August 1862.

At Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville he and his Mississippi brigade were always in the thick of the fight. “He possessed a “thirst for battle glory” wrote one Mississippian….Inspiring by example, Barksdale was a leader who dared to go where many other high-ranking officers would not go in a crisis situation.” [18] Barksdale had a strong bond with his soldiers which made them willing to follow him anywhere, one soldier wrote “of the comfort of his men he was most considerate, would tolerate no neglect of denial of their rights, or imposition on anyone. [19]

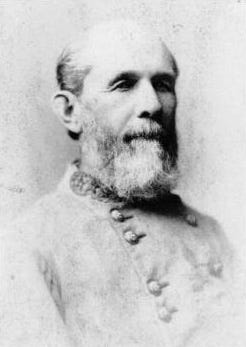

Brigadier General William Wofford

The other brigade commander of McLaws’s division's final strike was Brigadier General William Wofford. Wofford was the newest of McLaws’ brigade commanders, and in many respects was Barksdale’s opposite in temperament and politics, particularly in regard to secession. Wofford was born in Habersham County, Georgia in 1824. Educated in local schools “he studied law, was elected to the bar, and began a practice in Cassville, Georgia.” [20] In addition to his law practice, Wofford served as the editor for the Cassville Standard newspaper and was a respected leader in his community. Though he had no military education Wofford volunteered to serve during the Mexican War, as a Captain of “a battalion of Georgia mounted volunteers.” [21] where he experienced a great deal of fighting.

Wofford was considered a man of “high moral bearing…of the strictest sobriety, and, indeed of irreproachable moral character.” [22] Demonstrating the political tensions of the day Wofford was a “staunch Unionist Democrat” who “opposed secession and voted against it at the Georgia secession convention.” [23]

Despite his opposition to secession, Wofford, like others, considered loyalty to his state a higher ideal than to the Union, and when Georgia seceded he volunteered for service and was “elected colonel of the first Georgia regiment to volunteer for the war.” [24] Despite the contradiction of volunteering to serve his home state, Wofford “was a decided Union man from first to last during the whole war” and saw “with exceptional prescience…the certain fatality” of secession, but once the deed was done, he closed ranks…” [25] This may seem hard to comprehend in our present day, to men like Wofford it was not. When he went to war Wofford served well as the regimental commander of the 18th Georgia regiment, and served as an acting brigade commander during the Seven Days, Second Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. The able and experienced Georgia Unionist was promoted to brigadier general in January 1863 and given command of the brigade of Thomas Cobb, who had been mortally wounded at Fredericksburg.

These two men would lead Longstreet’s final attack of July 2nd, 1863. The fiery Mississippian and the pragmatic Georgian would lead their devoted soldiers in one of the fiercest charges of the war, one which pushed their Federal opponents to the limit before it was repulsed on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge. When the order to attack was relayed to Barksdale by McLaws’ aide-de-camp, Captain G.B. Lamar reported, when I carried him [Barksdale] the order to advance, his face was radiant with joy. He was in front of his brigade, his hat off, and his long white hair reminded me of ‘the white plume of Navarre.’” [26] Barksdale told, his regimental commanders “The line before you must be broken – to do so let every office and man animate his comrades by his personal presence in the front line.” [27]

As McLaws division attacked, Barksdale’s Mississippians broke through the Federal salient, “charged straight through a picket fence, knocking it down by sheer impact, and they shot and stabbed a Pennsylvania regiment that was dug in behind it, and after a flurry of hand-to-hand fighting under the shattered peach trees the Union defenders turned and ran and the peach orchard was gone.” [28] Porter Alexander wrote, “McLaws’s division charged past our guns, and the enemy deserted their line in confusion. Then I believed that Providence was indeed “taking the proper view” and that the war was very nearly over.” [29] But like many that day, Alexander’s instinct was wrong.

General Barksdale leads his Brigade at the Peach Orchard

Barksdale’s Mississippians drove forward through the Peach Orchard, through the men of Graham’s brigade, cheering and making the rebel yell, continuing to Plum Run, driving broken Federal regiments and batteries before them. “The Mississippi brigade drove forward at the double-quick and “literally rushed the goal,” tipping the rebel yell “with the savage courage of baited bulls” [30] Barksdale continued to lead his brigade forward though it had suffered significant casualties and was losing cohesion. Barksdale insisted on continuing to advance and would not stop to take time to reform his lines shouting at one of his regimental commanders “No! Crowd them – we have them on the run. Move your regiments.” [31] General Graham, attempted to rally his men and rode forward where he had his mount shoot out from under him. He then encountered Barksdale’s Mississippians who called on him to surrender. Graham, who had taken his adjutant’s mount replied “I won’t surrender. I’m a Brigadier General, and I won’t surrender.” [32] Undeterred the Mississippians shot his second mount out from under him and took him prisoner. “Graham had followed Sickles from their old days together in New York all the way to the Peach Orchard, and now would spend the next several months in captivity as his reward.” [33] As the Mississippians drove the remnants of Graham’s brigade to the rear, “the shattered line was retreating in separate streams[,] artillerists heroically clinging to their still smoking guns, and brave little infantry squads assisting their endangered cannon over soft ground…” [34]

Major General Dan Sickels

As the Third Corps line collapsed the Trostle farm where Sickles had made his headquarters became hot to remain in. At about six-thirty P.M. Sickles was riding up to a hill just above the Trostle barn, which would allow him a better view of his troops; the General was stuck by a Confederate round shot which stuck him in his right leg while leaving his mount unharmed. Sickles wrote:

“I never knew I was hit. I was riding the lines and was tremendously interested in the terrific fighting which was going on along my front. Suddenly I was conscious of dampness along the lower part of my right leg, and I ran my hand down the leg of my high-top boots and pulling it out I was surprised to see it dripping with blood. Soon I noticed the leg would not perform its usual functions. I lifted it carefully over my horse’s neck and slid to the ground. Then I was conscious of approaching weakness, and the last thing I remembered was designating the surgeons of my staff who should examine the wound and treat it. They found that the knee had been smashed, probably by a piece of shell and that the leg had been broken above and also below the knee; but while all this damage had been done, I had not been unhorsed, and never knew exactly what hurt had been received.” [35]

Third Corps dead at the Peach Orchard

Sickles ordered Major Tremain to find General Birney and said “Tell General Birney he must take command.” [36] as a tourniquet was placed on his leg and his soldiers prepared to evacuate him to the rear, thinking that his wound might well be mortal. When the stretcher-bearers arrived the wounded general, never missing a chance to build upon his legacy, “had an NCO light his cigar, and that was how he was carried away, cap over his eyes, cigar in mouth, hands folded on his chest.” [37] Sickles was taken to the rear by ambulance where his leg was amputated in a field hospital that night. A soldier of the 17th Maine wrote, “Our last sight of him in the field ambulance is one we shall long remember….He was sitting in an ambulance smoking and holding his shattered limb and appeared as cool as though nothing had happened.” [38] His surgeon was using , a new method of amputation and he had read that “the Army Medical Museum in Washington was advertising for samples, and so, instead of throwing the limb into a heap, he had it wrapped in a wet blanket and placed in a small coffin for shipment to Wash,ington.” [39] In the years following, Sickles paid his leg many visits, and it can still be viewed along with a round shot similar to the one that wounded him at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C.

The disaster that engulfed Sickles’ Third Corps now threatened the Federal center. Meade and Hancock rushed reinforcements in the form of Fifth Corps and much of Second Corps. The tip of Third Corps's salient at Sherfy’s Peach Orchard was manned by Graham’s brigade of David Birney’s division, was overwhelmed, and retreated in disorder. Once “the angle had been breached, the lines connecting to it on the east and north were doomed.” [40] This exposed the left of Humphrey’s division and it too was forced to retreat under heavy pressure while sustaining heavy casualties. In the final collapse of Humphrey’s division, a large gap was opened in the Federal lines between the elements of the Fifth Corps fighting along Devil’s Den and Little Round Top and the Second Corps along the central portion of Cemetery Ridge.

The Battle on the Plum Run Line July 2nd

When George Meade realized the seriousness of the situation he gave Sickles free rein to call for reinforcements from Harry Hunt’s Artillery Reserve as III Corps had only five batteries organic to it. Those five batteries were in the thick of the fighting providing invaluable support to Sickles’ hard-pressed and outnumbered corps. Firing canister and grapeshot they cut swaths of death and destruction through the massed ranks of wildly cheering Confederates of Kershaw and Semmes and Barksdale’s brigades of McLaws’ division. Kershaw recalled:

“The Federals…opened on these doomed regiments a raking fire of grape and canister, at short distance, which proved most disastrous, and for a time destroyed their usefulness. Hundreds of the bravest and best men of Carolina fell….” [41]

Lieutenant Colonel Freeman McGilvery

This Firey Line: The Artillery takes Charge

The Confederates believed that they had cut the Union line in half and advanced through the Peach Orchard and across the Wheat Field toward Cemetery Ridge. But they were to endure another furiously conducted defense, this by the artillery hastily collected along what is known as the Plum Run Line.

Among the artillery called into action was the First Volunteer Brigade under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Freeman McGilvery. McGilvery was a Maine native and a former sea captain who had left the high seas to volunteer to serve the Union cause. it was fortunate for the Union that this officer knew how to inspire his artillerymen with feats many thought unattainable in combat. On obtaining his commission as a Captain of Maine Volunteers, McGilvery organized and commanded the 6th Battery of the 1st Maine Volunteer artillery in January 1862.

McGilvery commanded that unit with distinction in a number of engagements. At the Battle of Cedar Mountain on August 9th, 1862, “During the battery’s baptismal fire, McGilvery and his Maine cannoneers, in one general’s opinion, had “saved the division from being destroyed or taken prisoners.” [42] A few days later, operating without infantry support yet again, “The battery performed spectacularly during the Second Manassas campaign, bringing recognition to its salty commander.” [43] He was promoted to Major in early 1863 and assumed command of the brigade during the Chancellorsville campaign. Following Chancellorsville McGilvery was given command of the newly formed First Volunteer Brigade of the Artillery Reserve. Barely a month later as the Army of the Potomac pursued Lee’s Army through Virginia and into Maryland he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel.

The 9th Massachusetts Battery goes into action

McGilvery’s battalion was directed by Brigadier General Robert Tyler, commander of the Artillery Reserve to assist Sickles. Henry Hunt met them on the road and directed them into position. McGilvery’s batteries arrived in the sector between 3:30 and 4:00 p.m. and “he was told by Sickles to examine the ground and pace the guns where he saw fit.” [44] He placed his four batters, some twenty-two guns in the Peach Orchard to support the artillery of Third Corps. Three batteries were placed in the Orchard itself near the Emmitsburg Road, and the fourth, the 9th Massachusetts under the command of Captain John Bigelow was deployed near the Trostle Farm. Without infantry support “It would be their job to hold the road down to the stony ridge by themselves.” [45] “Though hurt by enfilading fire from some of Alexander’s batteries, McGilvery’s guns in company with others from the reserve and the Third Corps had exchanged blow for blow with Confederate artillerymen for about two hours and had broken up the movements of some enemy infantry columns.” [46] These batteries were key in the first repulse of Kershaw and Semmes’ brigades at the stony ridge and which mortally wounded Semmes. McGilvery wrote:

“At about 5 o’clock a heavy column of rebel infantry made its appearance in a grain field, about 850 yards in front, moving at quick time toward the woods on our left, where infantry fighting was going on (front of the Round Tops). A well directed fire from all the batteries was brought to bear on them, which destroyed their order of march and drove many back into the woods on the right… In a few minutes another and larger column appeared, at about 750 yards, presenting a slight left flank to our position. I immediately trained the entire line of guns upon them and opened fire with various kinds of ammunition. The column continued to move on at double quick until it reached a barn and farm house immediately in front of my left battery (Bigelow’s) about 450 yards distant. When it came to a halt (a shot had killed its commanding officer) I gave them canister and solid shot with such good effect, that, I am sure that several hundred were put hors du combat in a short time….” [47]

The Union batteries continued a destructive fire against various Confederate regiments and brigades but suffered from Confederate artillery fire and close-in infantry assaults. Finally, “the pressure of the rebels became too great, and all of McGilvery’s batteries except Bigelow’s retired from this part of the field.” [48] Bigelow wrote, “No friendly supports of any kind were in sight…but Johnnie Rebs in great numbers. Bullets were coming in to our midst from many directions and a Confederate battery added to our difficulties.” [49]

McGilvery rode into the maelstrom of the retreating Third Corps soldiers and guns broken by Alexander’s withering fire. As he rode to and from each battery his horse was hit four times by enemy fire, but the salty artilleryman remained unwounded despite “exposing himself to enemy missiles on all parts of the field from Cemetery Ridge to the Peach Orchard.” [50] As McGilvery surveyed the scene he realized that there was no infantry in the immediate area that could plug the gap in the line. Taking the initiative, McGilvery acted instantly on his own authority to make a decision that in all likelihood saved the Union line.

In the confusion of the Third Corps disintegration, with soldiers fighting their way back to Cemetery Ridge and small groups and batteries attempting to keep their guns from being captured, McGilvery rode up to Bigelow and his 9th Massachusetts battery, which now stood alone at the Trostle farm. McGilvery told Bigelow, who was starting to make preparations to withdraw back to Cemetery Ridge, that he and his battery must “hold at all hazards.” [51]

Bigelow later explained that McGilvery told him that “for 4 or 500 yards in my rear, there were no Union troops.” He was then instructed by McGilvery, “For heavens [sic] sake hold that line…until he could get some other batteries in position…” [52] In another account, Bigelow recorded that McGilvery instructed him, “Captain Bigelow…there is not an infantryman back of you along the whole line which Sickles moved out; you must remain where you are and hold your position at all hazards, and sacrifice your battery if need be until at least I can find some batteries to put in position and cover you.” [53]

The order seemed suicidal. The 21st Mississippi was nearly upon them and they were but one battery and barely one hundred troops. Bigelow did not hesitate to obey; he brought his guns into line at the Trostle house, “facing one section slightly to the southwest and the other two sections directly into the path of the oncoming Confederates.” [54]

Henry Hunt described the action:

“Bigelow’s 9th Massachusetts made a stand close by the Trostle house in the corner of the through which he had withdrawn with prolonges, fixed. Although already much cut up he to hold that point until a line of artillery could be formed in front of the wood beyond Plum Run; that is, on what we now call the “Plum Run line.” [55]

Bigelow’s Drawings of the action at Trostle Farm

Bigelow’s artillerymen fought like demons he described the effect of his fire on Kershaw’s South Carolinians, “The Battery immediately enfiladed them with a rapid-fire of canister, which tore through their ranks and sprinkled the field with their dead and wound, until they disappeared in the woods on our left, apparently, a mob.” [56] They poured a merciless stream of fire into the advancing Confederates until “they had exhausted their supply of canister and the enemy began to close in on his flanks.” [57] A German-born gunner noted, “We mowed them down like grass, but they were thick and rushed up.” [58] A hand-to-hand fight ensued among the guns but the Massachusetts men escaped losing 28 of its 104 men engaged. [59] Their brave commander Bigelow was wounded and nearly captured, but one of his men helped him to the rear.

Their sacrifice was not in vain. They bought McGilvery an additional half an hour to set up a new line of guns along Plum Run, it was a masterful exercise of improvisation under incredible pressure. “This line was formed by collecting the serviceable batteries, that were brought off, with which, and with Dow’s Maine battery fresh from the reserve, the pursuit was checked. Finally some twenty-five guns formed a solid mass, which unsupported by infantry held this part of the line, aided General Humprheys’s movements, and covered by its fire the abandoned guns until the could be brought off, as all were, except perhaps one. When, after accomplishing its purpose, all that was left of Bigelow’s battery was withdrawn.” [60] Hunt praised the effort of Bigelow’s men to give McGilvery the necessary time to form his new gun line. “As the battery had sacrificed itself for the safety of the line, its work is specially noticed as typical of the service that artillery is not infrequently called to render, and did render in other instances at Gettysburg besides this one.” [61]

Barksdale’s brigade did not pause their relentless advance and continued in their relentless advance towards Cemetery Ridge, sweeping Union stragglers up as they moved forward led by their irrepressible General. Before them was McGilvery’s new line, hastily cobbled together from any batteries and guns that he could find. Initially, the line was composed of about fifteen guns from four different batteries and McGilvery was joined by two more batteries. This gave him a total of about twenty-five guns on the new line. Subjected to intense Confederate artillery fire and infantry attacks McGilvery’s batteries held on even as their numbers were reduced until only six guns remained operational. “Expertly directed by McGilvery a few stouthearted artillerymen continued to blaze away and keep the low bushes in front of them clear of lurking sharpshooters. Although they had no infantry supports, they somehow managed to create the illusion that the woods to their rear were filled with them, and they closed the breach until the Union high command could bring up reinforcements.” [62]

However, it was McGilvery who recognized the emergency confronting the line and on his own took responsibility to rectify the situation. He courageously risked “his career in assuming authority beyond his rank” [63] and without his quick action, courage under fire and expert direction of his guns, Barksdale’s men might have completed a breakthrough that could have won the battle for General Lee, despite all of the mistakes committed by his senior leaders that day.

It was another example of a Union officer who had the trust of his superiors who did the right thing at the right time. It is an example of an officer who used the principles of what we today call Mission Command to decisively impact a battle. McGilvery rose higher in the Federal service and was promoted to Colonel and command of the artillery of the Tenth Corps. He was slightly wounded in a finger at the battle of Deep Bottom in August 1864. The wound did not heal properly so surgeons decided to amputate the finger. However, during the operation, they administered a lethal dose of chloroform anesthesia to the brave colonel and he died on September 9th, 1864. When he died the Union lost one of its finest artillerymen. His body was returned to his native Maine and buried. However, he was not forgotten. In 2001 Maine legislature designated the first Saturday in September as Colonel Freeman McGilvery Day.

As Barksdale’s Mississippians advanced, Wofford’s Georgians moved forward on their right. It was the advance of Wofford’s men that caused Crawford’s men to pull back from the stony hill and the Wheatfield. That brigade “drove into the gap between the Peach Orchard and de Trobriand’s old position on Stony Hill. The Georgians were an especially welcome sight to Kershaw’s weary South Carolinians, trying to sort themselves out on Rose’s farm.” [64] The remnants of Kershaw’s brigade joined in the advance to the right of Wofford and forced the survivors of Zook, Kelly, and Sweitzer’s brigades from the Stoney Hill. The Confederates advanced driving the Union troops before them and plunged into the valley at the base of Little Round Top. Here they were met by the fresh Pennsylvania Reserves Division which launched a counterattack, “driving the Southerners back across the ridge and into the Wheatfield…and the fighting on that section of the battlefield on that section abated into deadly sharpshooting.” [65] Longstreet, knowing that nothing more could be done in the sector, ordered his troops back.

Barksdale’s advance also affected Humphrey’s division which up to this point had not been severely engaged and had acquitted itself well against elements of Richard Anderson’s division of A.P. Hill’s corps. When Sickles was wounded he turned command of the Third Corps over to Birney. In spite of being flanked by Barksdale and pressed by Anderson, Humphreys planned to counterattack, but Birney order him back to Cemetery Ridge. One of Humphreys’ aides recalled the scene, “The crash of artillery and the tearing rattle of our musketry was staggering, and added to the noise on our side, the advancing roar & cheer of the enemy’s masses, coming on like devils incarnate.” [66] Pressed hard, Humphreys pulled his troops back in a delaying action, and the division suffered about 1,200 casualties, “but it came out intact with morale sound and still full of fight.” [67]

The High Water Mark

Led by their exuberant commander the brigade pushed past the Trostle farm and into the Plum Run Valley, continuing to take casualties from the stubborn survivors of Third Corps. Now unsupported, Barksdale continued to press forward toward Cemetery Ridge, a soldier of the 13th Mississippi “recalled the sight of the mounted Barksdale encouraging the boys onward, yelling, “Forward through the brushes.” [68] Barksdale believed that he and his Mississippians could still wrest victory from defeat and he kept urging his decimated brigade forward in spite of the odds.

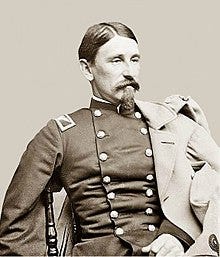

However, the tide was about to shift for the last time, as Barksdale’s survivors reached the lower portion of Cemetery Ridge a fresh Federal brigade arrived. Commanded by Colonel George Willard this brigade, struck the Mississippians with hard, in part seeking redemption. Willard’s brigade was one of the units forced to surrender at Harper’s Ferry the previous September. His troops were fresh and full of fight fell upon the Mississippians. “Taking advantage of the downhill grade, they charged headlong into the right flank of Barksdale’s brigade.” [69] As they did so the New Yorkers shouted, “Remember Harper’s Ferry! Remember Harpers Ferry!” “A short but terrible contest ensured in the bushes in the swale” and the Mississippians; “fire slackened and they began to give back.” As they did, “large numbers of them, staring at “the very points of our bayonets,” surrendered and “lay down in ranks.” [70]

Colonel George Willard

The attack by Willard’s brigade broke the back of Mississippians who had swept so many others before them. Now Barksdale’s troops were spent and disorganized, having reached the culminating point of their attack. When the two sides collided in the swale, “the New Yorkers were at the peak of their frenzy, while the Mississippians had spent theirs.” [71] Barksdale “in his gold-braided roundabout jacket, was “almost frantic with rage” at the repulse of his brigade, and “was riding at the front of his troops” and trying to make his men stand.” [72] He was now a conspicuous target and the men of 125th and 126th New York opened fire on him, hitting him “in the chest, puncturing a lung, and in his left leg fracturing a bone.” [73] The gallant officer fell from his horse, mortally wounded as his troops driven back by the New Yorkers. A party of Union soldiers recovered him and took him to a Federal field hospital where he “told his minders “tell my wife I fought like a man and I will die like one.” [74] The former Congressman died the next “morning, his thirst for glory slaked at last.” [75] His final opponent, Colonel George Willard did not live to savor the redemption that he and his brigade won that afternoon as he was hit “full in the face by a fragment of a shell and died instantly.” [76]

To the north of the salient Anderson’s division of Hill’s corps made a disjointed and uncoordinated attack toward Cemetery Ridge. Due to apparently garbled orders from Anderson, neither Carnot Posey’s nor “Little Billy” Mahone’s brigades advanced. Ambrose Wright’s troops went forward, but his claims to have breached the Federal line are romantic fiction at best, and David Lang’s tiny Florida brigade made only a desultory advance before retiring. Cadmus Wilcox’s brigade advanced unsupported up to Cemetery Ridge which due to the dispatch of troops to the Peach Orchard was only lightly defended.

When Hancock saw the threat he ordered the 1st Minnesota commanded by Colonel William Covill, who had a mere 262 soldiers to charge the advancing Confederates. Hancock told Covill: “Colonel, do you see those colors?…Then take them.” [77] Second Lieutenant Lochran of the regiment remembered the moment “Every man realized in an instant what that order meant, – death or wounds to us all; the sacrifice of the regiment to gain a few minutes time to save the position, and probably the battlefield…” [78] Covill’s tiny force “of a little over three hundred men tore into Wilcox’s right and stopped it cold.” [79] But the cost to the regiment was high, “Covill and all but three of his officers were killed or wounded, together with 215 of his men.” [80] Covill’s gallant troops bought time for Hancock to bring up Gibbon’s division which forth a heavy fire of musketry and were joined by the artillery which just minutes before had ravaged Barksdale’s Mississippians, staggered Wilcox’s regiments. Having taken a fair number of casualties he saw that he had no help or support from the rest of Anderson’s division, and reluctantly he withdrew his brigade from Cemetery Ridge. He later reported, “With a second supporting line the heights could have been carried. Without support on either my right or my left, my men were withdrawn to prevent their entire destruction or capture.” [81]

By the evening fresh Federal troops directed by Meade, Hancock and Hunt poured into the sector. Dan Sickles’ impetuous gamble was a near disaster for the Army of the Potomac, but the cool determination of his soldiers, the outstanding work of the Federal artillery, and the active leadership provided by Meade, Hancock, Warren, and Hunt enabled the army to repulse the Confederate assault. But it had been “another close call, staving off another Chancellorsville through unscripted decisions and split-second timing.” [82], By the end of the day despite sustaining massive casualties, the Federal Army held its ground, and the Confederates, except for their lodgment at Devil’s Den returned to their start positions.

The fighting around the Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, and Devil’s Den was confusing as units of both sides became mixed up and cohesion was lost. Both sides sustained heavy casualties but Lee’s Army could ill afford to sustain such heavy losses. By the end of the evening, both McLaws and Hood’s divisions were spent having lost almost half of their troops as casualties. Hood was severely wounded early in the fight, and many other Confederate commanders were killed or mortally wounded including the irrepressible Barksdale and Paul Semmes of McLaws’ division.

Amid the carnage there were acts of kindness shown towards one another by men who not long before had been mortal enemies. Private John Coxe of the 2nd South Carolina wrote:

“I felt sorry for the wounded enemy, but we could do little to help them. Just before dark I passed a Federal officer sitting on the ground with his back resting against a large oak tree. He called me to him, and when I went he politely asked me to give him some water. There was precious little in my canteen, but I let him empty it. His left leg was crushed just above the ankle, the foot lying on the ground sidewise. He asked me to straighten it up, and as I did so I asked him if the movement hurt him. “There isn’t much feeling in it now,” he replied quietly. Then before leaving him I said, “Isn’t this war awful?” “Yes, yes,” said he, “and all of us should be in a better business….” [83]

That evening the exhausted Confederate troops consolidated their positions on the few places where they had made lodgments in near the Federal line, tending to their wounded and seeking shelter among the rocks, trees and the dead. The Federal troops tended to the wounded around their lines while Henry Hunt’s artillerymen repaired their batteries as the night fell and their generals took counsel.

Notes

[1] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.193

[2] Ibid. Foote The Stars in Their Courses p.136

[3] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command, One volume abridgment by Stephen W Sears, Scribner, New York 1998 p.580

[4] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p.193

[5] Ibid. Longacre The Man Behind the Guns p.165

[6] Ibid. Alexander Fighting for the Confederacy p.239

[7] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery at Gettysburg p.119

[8] Ibid. Pfanz Gettysburg, the Second Day p. 312

[9] Ibid. Alexander Fighting for the Confederacy p.239

[10] Alexander, Edward Porter. The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume III The Tide Shifts Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel Castle, Secaucus NJ p.360

[11] Ibid. Longacre The Man Behind the Guns p.167

[12] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg pp.217-218

[13] Ibid. Dowdy. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg p.217

[14] Tucker, Phillip Thomas. Barksdale’s Charge: The True High Tide of the Confederacy at Gettysburg, July 2nd, 1863 Casemate Publishers, Philadelphia and Oxford 2013 p.14

[15] Ibid. Tucker Barksdale’s Charge p.15

[16] Ibid. Goldfield America Aflame p.144

[17] Freehling, William. The Road to Disunion Volume II: Secessionists Triumphant 1854-1861 Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2007 p.140

[18] Ibid. Tucker Barksdale’s Charge p.18

[19] Ibid. Tucker Barksdale’s Charge p.17

[20] Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of Confederate Commanders Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge 1959, 1987 p.343

[21] Ibid. Warner. Generals in Gray p.343

[22] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.296

[23] Ibid. Tagg The Generals of Gettysburg p.221

[24] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion p.297

[25] Ibid. Guelzo, Gettysburg: The Last Invasion pp.296-297

[26] Ibid. Dowdy Lee and His Army at Gettysburg p.221

[27] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p. 193

[28] Ibid. Catton Glory Road p.295

[29] Ibid. Alexander The Great Charge and the Artillery Fighting at Gettysburg p.360

[30] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg, the Last Invasion p.308

[31] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.368

[32] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg, the Last Invasion p.310

[33] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p. 202

[34] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg, the Testing of Courage p.368

[35] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p. 202

[36] Ibid. Swanberg Sickles the Incredible p.217

[37] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.288

[38] Ibid. Hessler Sickles at Gettysburg p. 207

[39] Ibid. Keneally American Scoundrel p.289

[40] Trudeau, Noah Andre Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage Harper Collins, New York 2002 p.368

[41] Ibid. Kershaw Kershaw’s Brigade at Gettysburg p.335

[42] Ibid. Tucker Barksdale’s Charge p.188

[43] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery at Gettysburg p.97

[44] Ibid. Gottfried The Artillery at Gettysburg p.97

[45] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg p.307

[46] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign a Study in Command p.415

[47] Bigelow, John The Peach Orchard Gettysburg, July 2nd 1863, Explained by Official Reports and Maps. Primary Source edition., Originally published by Kimball-Storer Co. Minneapolis 1910 p.20

[48] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign a Study in Command p.416

[49] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.384

[50] Coco, Gregory A. A Concise Guide to the Artillery at Gettysburg Colecraft Industries, Orrtanna PA 1998 p.31

[51] Hunt, Henry Proceeded to Cemetery Hill in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Bradford, Ned editor, Meridian Books, New York 1956 p.378

[52] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg p.314

[53] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.385

[54] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg a Testing of Courage p.385

[55] Hunt, Henry. The Second Day at Gettysburg in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War Volume III, The Tide Shifts. Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel Castle, Secaucus NJ p.310

[56] Bigelow, The Peach Orchard, 54; History of the Fifth, 638 retrieved from WE SAVED THE LINE FROM BEING BROKEN: Freeman McGilvery, John Bigelow, Charles Reed and the Battle of Gettysburg by Eric Campbell http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/gett/gettysburg_seminars/5/essay4.htm#52

[57] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.416

[58] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg the Last Invasion pp.314-315

[59] Ibid. Hunt Proceeded to Cemetery Hill p.379

[60] Ibid. Hunt The Second Day at Gettysburg p.310

[61] Ibid. Hunt Proceeded to Cemetery Hill p.379

[62] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.417

[63] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign p.417

[64] Ibid. Sears Gettysburg p.302

[65] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.262

[66] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg, the Testing of Courage p.379

[67] Nofi, Albert A. The Gettysburg Campaign June – July 1863 Third Edition Combined Publishing, Conshohocken, PA 1986 p.128

[68] Ibid. Tucker Barksdale’s Charge p.221

[69] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign a Study in Command p.417

[70] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg, the Last Invasion p.325

[71] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg, the Testing of Courage p.388

[72] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg, the Last Invasion p.325

[73] Ibid. Wert A Glorious Army p.262

[74] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg, the Last Invasion p.325

[75] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative: Fredericksburg to Meridian p.509

[76] Ibid. Tucker Barksdale’s Charge p.231

[77] Ibid. Trudeau Gettysburg, the Testing of Courage p.393

[78] Ibid. Gragg The Illustrated Gettysburg Reader p.222

[79] Ibid. Coddington The Gettysburg Campaign a Study in Command p.423

[80] Ibid. Foote The Civil War, A Narrative: Fredericksburg to Meridian p.509

[81] Ibid. Luvaas and Nelson Guide to the Battle of Gettysburg p.128

[82] Ibid. Guelzo Gettysburg, the Last Invasion p.334

[83] Ibid. Gragg The Illustrated Gettysburg Reader p.205

Private John Cox came upon a man who spoke the truth. This work of yours should be taught every day.