Reflecting on Christmas as a Madman Prepares to Take Office: Kurt Reuber and the Madonna of Stalingrad

A Retired Chaplain reflects on Faith and Serving in Unjust and Illegal Wars

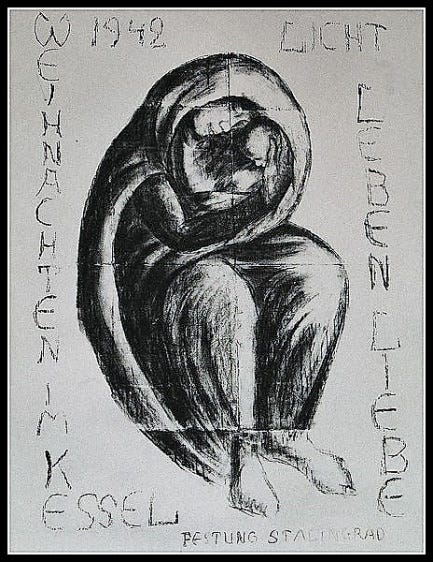

The Madonna of Stalingrad

Tonight I need to take a short break from the daily chaos of the Trump-Musk Axis of evil and reflect on history and my life. But also, the soldiers who serve in unjust and illegal wars, and my fears for the United States military once Trump becomes President.

As a Christian and priest, albeit one who struggles with faith daily, who fears most Christians and for whom the thought of going to church is frightening beyond belief. Someday I will write more about that another time, although I have mentioned in comments on an article by Steven Beschloss last week.

Over the past week I wrote two articles on my concerns regarding the military under Trump. The though of him, a convicted felon who pardoned war criminals during his first term and who has promised to remove and possibly prosecute active duty and retired officers, as well as “fire” currently serving military leaders because he questions their personal loyalty to him, or has labeled them as “woke” is troubling. Likewise, his desire to appoint Pete Hegseth, as the Secretary of Defense is very troubling. Hegseth does not have the professional, military experience, or education to serve as Secretary of Defense. He has never commanded a unit larger than a platoon, and he has completed no advanced military education. Additionally, his personal ethics and behavior would in normal times have disqualified him from any senior position in the Department of Defense. Trump and Hegseth bring a level of incompetence and malevolence to the control of the military unseen in our history, and that, along with the loyalists he promotes to the highest leadership positions in the military bodes ill for our troops and our country, at home and abroad.

I think most of my readers now know that I am a career military officer and have served in peace and war as a chaplain. That service includes a tour in Iraq, a war, which by almost any standard would have been considered unjust and illegal, and would have easily met the criteria that we charged, tried, found guilty and executed for in the Nuremberg trials.

Yet, I volunteered to serve there during the surge of 2007. My Christmas while serving our advisors and our Iraqis on the Iraq-Syria border was probably the most important and meaningful of my life as a Priest and Chaplain, but that too is a story for another time. I came back a changed man. As such the stories of those who served in war, especially those who served in hopeless battles, and even in evil causes during Christmas have a special place in my heart. One of those men was a German pastor and medical doctor named Kurt Reuber.

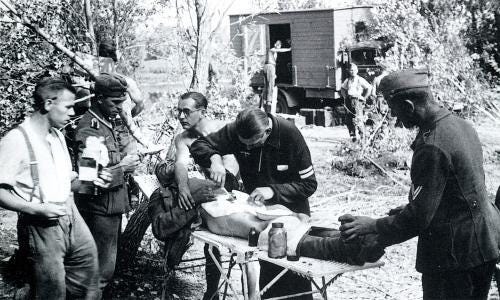

Kurt Reuber doing surgery on a wounded German soldier in 1942

As I said, Reuber was a theologian, pastor and medical doctor, likewise he was an accomplished artist and used that medium to convey his own faith, and doubts. He was a friend of Albert Schweitzer and in 1939 he was conscripted to serve as a physician in the Germany Army. By November 1942 he was a seasoned military physician serving with the 16th Panzer Division which was part of the German 6th Army, which had been fighting in the hell of Stalingrad. When his division along with most of 6th Army was surrounded by the Soviets and cut off from most supply and without real hope of relief, he, like other physicians continued to serve the soldiers committed to his care.

However, unlike most physicians, the care Reuber offered care included spiritual matters, as he sought to help his soldiers deal with the hopelessness of their situation. As Reuber reflected on the desperation of the German soldiers in the Stalingrad pocket, he decided to paint something that reflected faith. He wrote a letter to his family:

“I wondered for a long while what I should paint, and in the end I decided on a Madonna, or mother and child. I have turned my hole in the frozen mud into a studio. The space is too small for me to be able to see the picture properly, so I climb on to a stool and look down at it from above, to get the perspective right. Everything is repeatedly knocked over, and my pencils vanish into the mud. There is nothing to lean my big picture of the Madonna against, except a sloping, home-made table past which I can just manage to squeeze. There are no proper materials and I have used a Russian map for paper. But I wish I could tell you how absorbed I have been painting my Madonna, and how much it means to me.”

“The picture looks like this: the mother’s head and the child’s lean toward each other, and a large cloak enfolds them both. It is intended to symbolize ‘security’ and ‘mother love.’ I remembered the words of St. John: light, life, and love. What more can I add? I wanted to suggest these three things in the homely and common vision of a mother with her child and the security that they represent.”

The picture was drawn on the back of a captured Soviet map and when he finished it he displayed it in his bunker, which became something of a shrine. Reuber wrote:

“When according to ancient custom I opened the Christmas door, the slatted door of our bunker, and the comrades went in, they stood as if entranced, devout and too moved to speak in front of the picture on the clay wall…The entire celebration took place under the influence of the picture, and they thoughtfully read the words: light, life, love…Whether commander or simple soldier, the Madonna was always an object of outward and inward contemplation.”

German POWs at Stalingrad

On January 9th 1943 with all hope of escape or reinforcement gone Reuber gave the painting to his battalion commander. The officer was too ill to carry on and was one of the last soldiers to be evacuated from Stalingrad. Reuber’s commander carried the Madonna out of the pocket and returned it delivered it to Reuber’s family, preserving it for all.

German POWs being marched our of Stalingrad

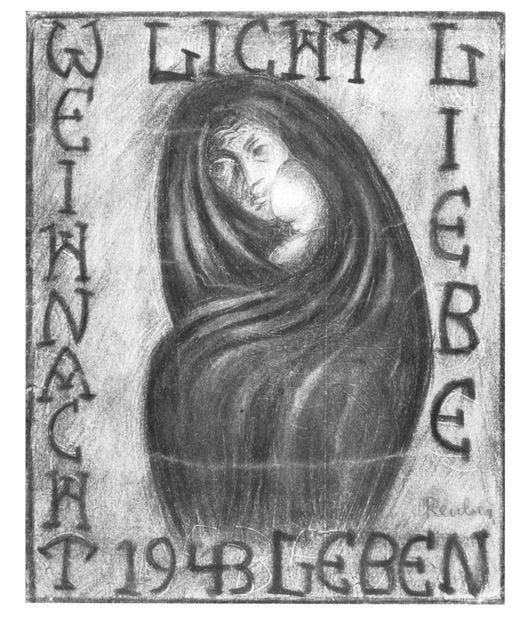

Reuber was taken prisoner and survived the harrowing winter march to the Yelabuga prison camp. In late 1943 Reuber wrote his Christmas Letter to a German Wife and Mother – Advent 1943.

It was a spiritual reflection but also a reflection on the hope for life after the war, when the Nazi regime would be defeated, and Germany given a new birth. I wonder if the Christians currently swearing their fealty to President Trump will be capable of such reflection when his regime finally collapses, regardless of how and when it does. Twenty or so years ago I would have quite likely been part of Trump’s cult of “Christian” followers.

Reuber wrote:

“The concatenation of guilt and fate has opened our eyes wide to the guilt. You know, perhaps we will be grateful at the end of our present difficult path yet once again that we will be granted true salvation and liberation of the individual and the nation by apparent disappointment of our “anticipation of Advent”, by all of the suffering of last year’s as well as this year’s Christmas. According to ancient tradition, the Advent season is simultaneously the season of self-reflection. So at the very end, facing ruin, in death’s grip – what a revaluation of values has taken place in us! We thus want to use this period of waiting as inner preparation for a meaningful new existence and enterprise in our family, in our vocation, in the nation. The Christmas light of joy is already shining in the midst of our Advent path of death as a celebration of the birth of a new age in which – as hard as it may also be – we want to prove ourselves worthy of the newly given life.” (Erich Wiegand in Kurt Reuber, Pastor, Physician, Painter, Evangelischer Medienverb. Kassel 2004.)

A Self-Portrait of Kurt Reuber

Reuber did not live to see that day. He died of Typhus on January 20th 1944, not long after writing this. Likewise, he died only few weeks after painting another portrait of the Madonna, this one entitled The Prisoner’s Madonna. He was not alone, of the approximately 95,000 German POWs taken at Stalingrad only about 6,000 returned home.

His paintings survived the war. His family gave The Madonna of Stalingrad to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin after it was restored as a symbol of hope and reconciliation. Copies are also displayed in Coventry Cathedral which was destroyed during the Nazi bombing of that city, and the Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Volgograd, the former Stalingrad. A copy of The Prisoner’s Madonna is now displayed at the Church of the Resurrection in Kassel.

The Prisoner’s Madonna

I have kept a print of the Madonna of Stalingrad in my office since my tour in Iraq until my retirement in December 2020. It is now in my home office and library. It is one of the most meaningful pictures I own. To me the print is a symbol of God’s presence when God seems entirely absent, he does so often today.

I now pray for an end to tyranny and war, and I will resist both in the face of what is to come.

This is deeply meaningful to me. As a boy Stalin’s soldiers murdered my father’s family, leaving him an orphan, at what age unknown. He was in a displaced persons (DP) camp for years. When he was going to be shipped to Siberia a Christian org helped him escape. During the escape they were rounded up into a barn by Nazi’s and were going to be burned alive. How did they get out? US soldiers saved them. My father made it to the USA, alone, at the age of 13. I don’t think I will ever know the details of his youth, he never talked about it. We didn’t know his real name until after he died. But I am reading about the time 1937 to 1950, in an attempt to understand, and find compassion for, the man that was my father, who was sadly broken.

Our eldest son was deployed to Iraq, ‘06-‘07, as a part of the Iraqi police transition program, which he believed had little utility. Our son was an Air Force security forces NCO, retired a couple of years ago. He has worked his way through PTSD and physical disabilities. Seems to be in a better place today.