Remembering the Rape of Nanking

“As the Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel warned years ago, to forget a holocaust is to kill twice.” Iris Chang

Eighty-seven years ago Japanese Army troops under the command of Lieutenant General Asaka Yasuhiko launched an attack on the Nationalist Chinese defenders of the city of Nanking. That attack and the subsequent occupation led to one of the most heinous displays of inhumanity and war crimes in modern history. As a single event it ranks as high or higher than any single event directed at one city during the Nazi Holocaust against the Jews.

The massacre, which occurred in 1937 was one of the most extensively documented war crimes in modern history. But despite that there are many, especially those of Japanese political right who deny that the event ever occurred and if any atrocities happened in Nanking it was the Chinese government which carried them out. The Japanese who deny the massacre are no better than Holocaust deniers.

The Rape of Nanking in 1937 by the Japanese Army is hotly debated with right wing Japanese historians and politicians lining up against legitimate historians armed with indisputable evidence. [1] The massacres began during the initial occupation of the city and continued over the two months following it. The actions of the Japanese were reported by western journalists and even a German Nazi Party member by the name of John Rabe. Rabe assisted in protecting Chinese during the massacre and reported it on his return to Germany. The actions of the Japanese Army shocked many in the west and helped cement the image of the Japanese being a brutal race bent on conquest and murder.

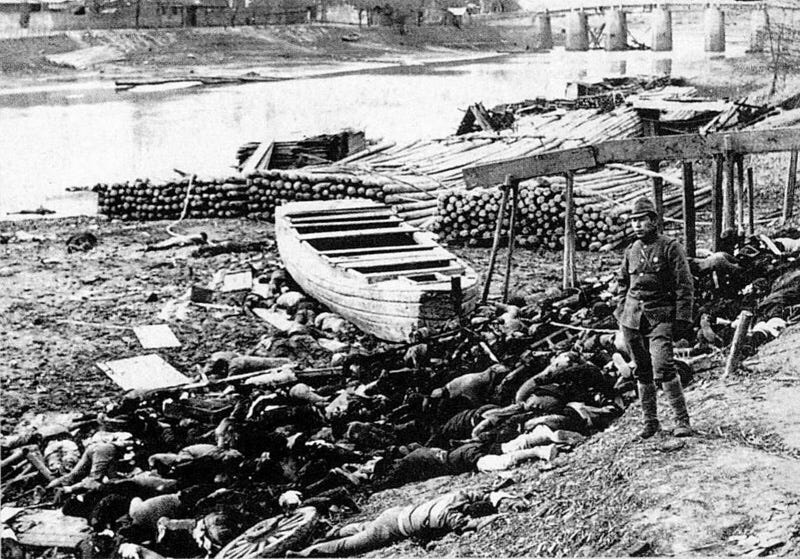

Victims of the Japanese Atrocities

The controversy’s visibility was raised since the 1997 publication of Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking. However, with few exceptions the incident had received little attention by Western historians until Chang’s book was published. The reason for this was that China was a sideshow for for the United States and Britain throughout much of the war. When Chiang Kai Shek’s Nationalists were overthrown by the Communists in 1948 the incident disappeared from view in the United States. The United States government reacted to the overthrow of Chaing by helping to rebuild Japan and rehabilitate the Japanese while opposing the Chinese Communists. In fact it was only “after the Cold War was the Rape of Nanking openly discussed.”[2]

Japanese Troops Engaged in Killing

Chang’s book was instrumental as it brought new attention to the atrocities of the Japanese Army in their slaughter of Prisoners of War and civilians following the occupation of the city. However, even as Chang’s work was published “revisionist” works began to appear in Japan the which either denied the atrocities, sought to minimize numbers killed by Japanese Army, or rationalized the the massacre began to appear in Japan. The revisionists were led by Masaaki Tanaka who had served as an aide to General Matsui Iwane the commander of Japanese forces at Nanking. Tanaka denied the atrocities outright calling them “fabrications” casting doubt upon numbers in the trial as “propaganda.” He eventually joined in a lawsuit against the Japanese Ministry of Education to remove the words “aggression” and “Nanjing massacre” from textbooks, a lawsuit which was dismissed but was influential among other revisionists and Japanese nationalist politicians and publishers.[3]

Chinese Children Murdered at Nanking

Most early accounts of the occupation and war crimes used a number of 200,000 to 300,000 victims based upon the numbers provided during the War Crimes Trials of 1946.[4] Unlike the numbers of victims of the Nazi Holocaust the numbers are less accurate. Authors who maintain the massacres such as Chang and others such as Japanese military historian Mashario Yamamoto who admits Japanese wrongdoing and excess but challenges the numbers use the same statistical sources to make their arguments. Chang not only affirms the original numbers but extrapolates them and suggests that even more Chinese may have been killed. She asserted that the disposal of the victim’s bodies in the Yangtze River rather than in mass graves away from the city as were most victims, as well as the failure of survivors to report family member deaths to the Chinese authorities.[5] She also cited contemporary Chinese scholars who suggest even higher numbers.

Prince Asaka (above) and General Matsui (below)

Historian Herbert Bix discussed Japanese knowledge of the atrocities in detail up and down the chain of command including Prince Asaka, the granduncle of Emperor Hirohito who commanded troops in Nanking, the Japanese military and Foreign Office, and likely even Emperor Hirohito himself.[6]

German National and Nazi Party Member John Rabe, protected Chinese at Nanking and reported what he witnessed to the German Government. Before the occupation he represented Siemens company in China. While in Nanking he founded a German school for Chinese in 1934. He is known as “The Good Man of Nanking.” He admired Hitler, a fact that other Westerners found it hard to reconcile with his humanity and selfishness towards the Chinese in the Protection Zone. On 10 December he wrote: “If you can do some good, why hesitate.” But even before the attack he explained his motivation to remain in Nanking:

“Our Chinese servants and employees, about 30 people in all including immediate families, have eyes only for their “master.” . . . I cannot bring myself for now to betray the trust these people have put in me. And it is touching to see how they believe in me. . . . Under such circumstances, can I, may I, cut and run? I don’t think so. Anyone who has ever sat in a dugout and held a trembling Chinese child in each hand through the long hours of an air raid can understand what I feel.”

John Rabe

Rabe’s diaries were published in 2000 under the title, The Good Man of Nanking, provided an additional first hand account by a westerner who had the unique perspective of being from Japan’s ally, Nazi Germany. His accounts buttress the arguments of people like Chang’s who seek to inform the world about the size and scope of Japanese atrocities in Nanking. In his diary, Rabe, who saved nearly 200,000 Chinese civilians from slaughter wrote:

“Two Japanese soldiers have climbed over the garden wall and are about to break into our house. When I appear they give the excuse that they saw two Chinese soldiers climb over the wall. When I show them my party badge, they return the same way. In one of the houses in the narrow street behind my garden wall, a woman was raped, and then wounded in the neck with a bayonet. I managed to get an ambulance so we can take her to Kulou Hospital … Last night up to 1,000 women and girls are said to have been raped, about 100 girls at Ginling College … alone. You hear nothing but rape. If husbands or brothers intervene, they’re shot. What you hear and see on all sides is the brutality and bestiality of the Japanese soldiers.”

The words of Japanese soldiers, like Lance Corporal Meguro Fukuji, often bear this out. Fukuji wrote on 16 December, that outside the city:

“At 4:00 p.m. we shot to death 7,000 prisoners taken by the Yamada Unit [Detachment]. The cliff on the Yangtze looked like a mountain of corpses from a time. That was an awful site.”

Japanese Officers standing over dead Chinese

Dr. Robert O. Wilson, an American physician in Nanking wrote:

“The slaughter of civilians is appalling. I could go on for pages telling of cases of rape and brutality almost beyond belief. Two bayoneted corpses are the only survivors of seven street cleaners who were sitting in their headquarters when Japanese soldiers came in without warning or reason and killed five of their number and wounded the two that found their way to the hospital.

Let me recount some instances occurring in the last two days. Last night the house of one of the Chinese staff members of the university was broken into and two of the women, his relatives, were raped. Two girls, about 16, were raped to death in one of the refugee camps. In the University Middle School where there are 8,000 people the Japs came in ten times last night, over the wall, stole food, clothing, and raped until they were satisfied. They bayoneted one little boy of eight who [had] five bayonet wounds including one that penetrated his stomach, a portion of omentum was outside the abdomen. I think he will live.”

A Field of Skulls at Nanking

The Legation Secretary of the German Embassy wrote to the Foreign Ministry In Berlin:

“On December 13, about 30 soldiers came to a Chinese house at No. 5 Hsing Lu Koo in the southeastern part of Nanking, and demanded entrance. The door was open by the landlord, a Mohammedan named Ha. They killed him immediately with a revolver and also Mrs. Ha, who knelt before them after Ha’s death, begging them not to kill anyone else. Mrs. Ha asked them why they killed her husband and they shot her. Mrs. Hsia was dragged out from under a table in the guest hall where she had tried to hide with her 1 year old baby. After being stripped and raped by one or more men, she was bayoneted in the chest, and then had a bottle thrust into her vagina. The baby was killed with a bayonet. Some soldiers then went to the next room, where Mrs. Hsia’s parents, aged 76 and 74, and her two daughters aged 16 and 14 [were]. They were about to rape the girls when the grandmother tried to protect them. The soldiers killed her with a revolver. The grandfather grasped the body of his wife and was killed. The two girls were then stripped, the elder being raped by 2–3 men, and the younger by 3. The older girl was stabbed afterwards and a cane was rammed in her vagina. The younger girl was bayoneted also but was spared the horrible treatment that had been meted out to her sister and mother. The soldiers then bayoneted another sister of between 7–8, who was also in the room. The last murders in the house were of Ha’s two children, aged 4 and 2 respectively. The older was bayoneted and the younger split down through the head with a sword.”

Masahiro Yamamoto who is a military historian by trade and is viewed as a “centrist” in the debate, places the massacres in the context of Japanese military operations beginning with the fall of Shanghai up to the capture of Nanking. Yamamoto criticizes those who deny the massacres but settles on a far lower number of deaths, questioning the numbers used at the War Crimes Trials. He blames some on the Chinese Army[7] and explains many others away in the context of operations to eliminate resistance by Chinese soldiers and police who had remained in the city in civilian clothes. He claims that “the Japanese military leadership decided to launch the campaign to hunt down Chinese soldiers in the suburban areas because a substantial number of Chinese soldiers were still hiding in such areas and posing a constant threat to the Japanese.”[8] David Barrett in his review of the Yamamoto’s work notes that Yamamoto believes that “there were numerous atrocities, but no massacre….”[9] Yoshihisa Tak Mastusaka notes that while a centrist Yamamoto’s work’s “emphasis on precedents in the history of warfare reflects an underlying apologist tone that informs much of the book.”[10]

Revisionists also criticize the trials surrounding Nanking and other Japanese atrocities. An example of such a work is Tim Maga’s Judgment at Tokyo: The Japanese War Crimes Trials which is critiqued by historian Richard Minear as “having a weak grasp of legal issues” and “factual errors too numerous to list.”[11] Such is a recurrent theme in revisionist scholarship, the attempt to mitigate or minimize the scale of the atrocities, to cast doubt upon sources and motivations of their proponents or sources, to use questionable sources themselves or to attribute them to out of control soldiers, the fog of war and minimize command knowledge as does Yamamoto. Politics is often a key motivating factor behind revisionist work.

General Matsui Riding into Nanking

But the testimony of General Matsui before and after the war crimes trials in which he was convicted and sentenced to death is damning and exposes the lies of the revisionists for what they are. Matsui confessed to one of his aides:

“I now realize that we have unknowingly wrought a most grievous effect on this city. When I think of the feelings and sentiments of many of my Chinese friends who have fled from Nanjing and of the future of the two countries, I cannot but feel depressed. I am very lonely and can never get in a mood to rejoice about this victory … I personally feel sorry for the tragedies to the people, but the Army must continue unless China repents. Now, in the winter, the season gives time to reflect. I offer my sympathy, with deep emotion, to a million innocent people.”

Before his execution Matsui testified of his guilt:

“The Nanjing Incident was a terrible disgrace … Immediately after the memorial services, I assembled the higher officers and wept tears of anger before them, as Commander-in-Chief … I told them that after all our efforts to enhance the Imperial prestige, everything had been lost in one moment through the brutalities of the soldiers. And can you imagine it, even after that, these officers laughed at me … I am really, therefore, quite happy that I, at least, should have ended this way, in the sense that it may serve to urge self-reflection on many more members of the military of that time.”

Iris Chang

Chang would never be the same after researching and writing the Rape of Nanking. Traumatized by what she had learned in her research and writing, and burdened by the weight of what she had taken on, she killed herself on November 9th 2004, her death probably brought on by the prescription of various antidepressants which had a side effect of suicidal ideation, which amplified the weight of her burdens, which included researching a book on an American army unit during the Bataan Death March.

A Chinese Woman with a Bayonet in her Vagina

“Revisionist” history, like those of the Japanese apologists for Japan’s war crimes in China, and throughout Asia before and during the Second World War will almost certainly remain with us, so long as people study the past. However one has to be careful in labeling a divergent view of a historical subject as necessarily revisionist. There are occasions when new evidence arises and a “new” or “revisionist” work may actually disprove previous conclusions regarding historic events or persons, such as the work of American historians to disprove the “histories” written by Confederate apologists that dominated the history of the American Civil War from the 1880s to the 1960s. This might occur when what we know about a subject comes from a single or limited number of sources who themselves were limited in what they had available for research and new evidence comes to light. At the same time where numerous sources from diverse points of view attest to the genuineness of an event, the revisionist’s theses should be themselves scrutinized based on evidence presented as well as their political, ideological or racial motivations. While one does not want to silence voices of opposition to prevailing beliefs one has to be careful in examining their claims, especially when they arise in the context of political or ideological conflicts.

That being said, Iris Chang did Americans and the Western World a profound service by reopening the study of the Rape of Nanking, and by standing up to the opposition of the Japanese government, Japanese media, and Japanese revisionist historians. Her passion for the truth is a reminder that historians, as well as journalists cannot abandon the truth regardless of the cost.

Thorough and well researched.

What was a dim memory, has become a graphic depiction of a human flaw. Cruelty hath no bounds!

Self-sacrifice by a writer.

Her act of self-slaughter, coupled by antidepressants and Hari-Kari may have induced her suicide.

Typo in the beginning paragraphs, describing the German who intervened and exposed the Japanese atrocities in Nanking. (selfish/selfless).

Truth is, contradictions are a underlying factor in human behaviour!