Robert E. Lee and George Meade: A Study in Command and Leadership at Gettysburg on the Night of July 2nd, 1863

Here is another portion of my Gettysburg Staff Ride Text. This part doesn’t deal with the fighting. Instead, it deals with how General Robert E. Lee, commanding the Army of Northern Virginia, and Major General George Gordon Meade, commanding the army of the Potomac, planned for July 3rd at Gettysbu,rg.,,,, The differences are stark. In this chapter I decided to tackle the elephant in the room when it comes to the alleged greatness of General Robert E. Lee.

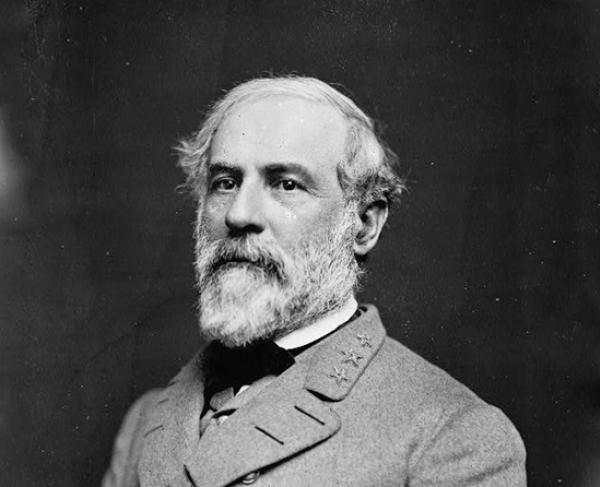

The Mythology of the Lost Cause elevated Robert E. Lee to be one of the greatest, if not the greatest general in American history. Like many people of my generation, almost everything I read about Lee was what a great General, American, and Christian he was, and like many people, I believed it. There was little mention of his active support of slavery, his cruelty to and refusal to release slaves left to him by his mother as she desired, or his sedition and treason against the United States. But that is another story. Today we deal with Lee’s incompetence at the tactical and operational levels of war at Gettysburg, and his willful ignorance of his own situation and what was facing him a little over a mile away.

At the same time the chapter juxtaposes Lee’s hubris with the often underrated opposing commander of the Army of the Potomac, Major General George Meade. Lee’s actions are described in the first section, while Meade’s which in an edited form are a vignette in Army Doctrine Publication 5-0, The Operations Process. Unlike Lee, Meade listened to his staff and sought the counsel of his subordinate commanders. Likewise, where Lee never left his headquarters on Seminary Ridge, observing the battle from a distance of almost two miles away on 2 July, Meade was in the thick of the action at numerous threats throughout the battle. Thus, unlike Lee, who knew nothing of the real situation on the battlefield and the condition of his Army and did not want to know it, Meade knew the situation and then, that night, sought the counsel of his Corps Commanders and Staff.

This is an important point to note when evaluating the Generalship of Robert E. Lee. In every battle except Fredericksburg and Cold Harbor where he was on the defensive and his army well dug in, he always lost a higher percentage of his troops engaged than his Union counterparts, even when he won. If an Army commander knows that he cannot match the overwhelming numerical and firepower advantage of his opponent, he has to do everything that he can to husband his soldiers and not waste their lives in battles that, even if won, would not materially alter the course of the war is either incompetent, negligent or so arrogant in regards to their abilities, that they cannot be regarded as great commanders. To do so is to propagate a murderous myth.

Part One: Lee

As night fell on July 2nd, 1863 General Robert E Lee had already made his decision. Despite the setbacks of the day he was determined to strike the Army of the Potomac yet again. He did not view the events as a setback, and though he lacked clarity of how badly many of his units were mauled, Lee took no external counsel to make his decision; his mind was made up, and he neither wanted advice nor counsel. By now, Lee’s subordinate commander's opinions were irrelevant. To that end, every day of the Battle of Gettysburg, he refused any counsel that did not agree with his vision, which had become myopic and disconnected from the reality faced by his rebellious nation and the Army he led.

After two full days of brutal combat, his forces had failed to break the Union defenses, and the Army of the Potomac’s commanders out-generaled Lee’s commanders time and time again. Every division that Lee threw at the Union defenses suffered 40% casualties or more on the first two days of battle. His casualties included one division commander, Dorsey Pender, who was mortally wounded, and three others, John Bell Hood, Harry Heth, and Robert Rodes were wounded. Likewise, numerous brigade and regimental commanders, including some of his best, had been killed or wounded.

With the exception of A.P. Hill who came and submitted a report to him at dusk on July 2nd, Lee neither required his other two corps commanders, James Longstreet or Richard Ewell to consult with him. Not did he take any action to visit them. Lee now lived in a bubble, and his very small staff were nothing more than ciphers. They were there to transmit orders, not to assist in the planning or coordinating his army’s operations.

Despite the massive casualties and being repulsed all along the line, Lee did “not feel that his troops had been defeated,” he felt that “the failure on the second day had been due to a lack of coordination.” [1]

In his official report of the battle he wrote:

“The result of this day’s operations induced the belief that, with proper concert of action, and with the increased support that the positions gained on the right would enable the artillery to render to the assaulting columns, that we should succeed, and it was ultimately determined to continue the attack…” [2]

While Lee’s charge of a “lack of coordination” of the attacks can certainly be substantiated. However, if there was anyone to blame for his lack of coordination it was Lee. Even Lee’s most devoted biographer Douglas Southall Freeman wrote that on July 2nd “the Army of Northern Virginia was without a commander.” [3] Likewise, Lee’s decision to attack on July 3rd, having not taken counsel of his commanders or assessed the battle-worthiness of the units that he was planning to use in his final assault on the Union center was “utterly divorced from reality.” [4] His plan was essentially unchanged from the previous day. Longstreet’s now battered divisions were to renew their assault on the Federal left in coordination with Pickett and two of Hill’s divisions.

In light of Lee’s belief that “a lack of coordination” was responsible for the failures of July 2nd it would have been prudent for him to ensure such coordination happened on the night of July 2nd. “Lee would have done well to have called out his three lieutenants to confer with them and spell out exactly what he wanted. That was not the way he did things…” [5] However, Lee took no such action.

Lee knew about the heavy losses among his key leaders but “evidently very little was conveyed to him regarding the condition of the units engaged this day.” [6] This certainly had to be because during the day his only view of the battlefield was from Seminary Ridge through binoculars, a view often obscured by the smoke of the battle, and because he did not get first-hand reports from the commanders involved. Nonetheless, Lee was undeterred and according to some who saw Lee that night, he seemed confident, noting that when Hill reported, he shook his and said, “It is well, General…Everything is well.” [7]

It was not an opinion that Lee’s subordinates shared. Ewell and his subordinates were told to renew their attack on Cemetery and Culp’s Hill on the night of July 2nd, but “he and his generals believed more than ever that a daylight assault against the ranked guns on Cemetery Hill would be suicidal-Harry Hays said that such an attack would invite “nothing more than slaughter…” [8]

James Longstreet was now more settled in his opposition to another such frontal attack and shortly after dawn when Lee visited him to deliver the order to attack again argued for a flanking movement around the Federal left. Lee’s order was for Longstreet to “attack again the next morning” according to the “general plan of July 2nd.” [9] Longstreet had not wanted to attack the previous day, and when Lee came to him Longstreet again attempted to persuade Lee of his desire to turn the Federal flank. “General, I have had my scouts out all night, and I find that you still have an excellent opportunity to move around to the right of Meade’s army and maneuver him into attacking us.” [10]

Lee would have nothing of it. He looked at his “Old Warhorse” and as he had done the previous day insisted: “The enemy is there,” he said, pointing northeast as he spoke, “and I am going to strike him.” [11] Longstreet’s gloom deepened and he wrote that he felt “it was my duty to express my convictions.” He bluntly told Lee:

“General, I have been a soldier all of my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions and armies, and should know, as well as any one, what soldiers can do. It is my opinion that no fifteen thousand men ever arranged for battle can take that position.” [12]

But Lee was determined to force his will on both his subordinates and the battle. Lee was convinced that the plan could succeed while Longstreet “was certain” that the plan “was misguided and doomed to fail.” [13] Longstreet, now realized that further arguments were in vain, recalled that Lee “was impatient of listening, and tired of talking, and nothing was left but to proceed.” [14]

Even a consultation with Brigadier General William Wofford whose brigade had helped crush Sickle’s III Corps at the Peach Orchard and had nearly gotten to the crest of Cemetery Ridge could not alter Lee’s plan. Wofford had to break off his attack on July 2nd when he realized that there were no units to support him. Lee asked if Wofford could “go there again” to which Wofford replied, “No, General I think not.” Lee asked “why not” and Wofford explained: “General, the enemy have had all night to intrench and reinforce. I had been pursuing a broken enemy, and now the situation is very different.” [15]

The attack would go forward despite Longstreet’s objections and the often unspoken concerns of others who had the ear of Lee, or who would carry out the attack. Walter Taylor of Lee’s staff wrote to his sister a few days after the attack the “position was impregnable to any such force as ours.” At the same time, Pickett’s brigadier Richard Garnett remarked, “This is a desperate thing to attempt,” and Lewis Armistead said, “The slaughter will be terrible.” [16]

Pickett’s fresh division would lead the attack. He would be supported by Johnston Pettigrew who was commanding the wounded Harry Heth’s division of Hill’s Third Corps, and Isaac Trimble, now commanding two brigades of Pender’s division. Trimble was given command just minutes prior to the artillery bombardment. [17] None of the commanders had commanded alongside each other before July 3rd. Trimble had just recovered from wounds had never been with his men. Pettigrew assumed command when Pender was wounded on July 1st, and was still new and relatively untested. Pickett’s three brigadiers and their brigades had never fought together. Likewise, Pettigrew and Trimble’s divisions had never served under Longstreet. From a command perspective where relationships and trust count as much as strength and numbers, the situation was nearly as bad is it could be.

In addition, while the Confederates massed close to 170 cannon on Seminary Ridge to support the attack, ammunition was in short supply, and Lieutenant Colonel Porter Alexander, who had been tasked with coordinating fire, only controlled the guns of Longstreet’s First Corps.

The assaulting troops would have to attack with their right flank exposed to deadly enfilade fire from Federal artillery from Little Round Top and Plum Run, while the left flank was unsupported and exposed to artillery fire from the massed Union artillery on Cemetery Hill. It was a disaster waiting to happen. Longstreet noted, “Never was I so depressed as on that day…” [18]

Part Two: Meade

While Lee took no counsel when he decided to attack on the night of July 2nd, little more than two miles away Major General George Meade took no chances. After sending a message to Henry Halleck at 8 PM Meade called his generals together. Unlike Lee who had only observed the battle from a distance, Meade had been everywhere on the battlefield during the day and had a good idea of what his army had suffered and the damage that he had inflicted on the Army of Northern Virginia. Likewise, during the day Meade had been with the majority of his commanders as opposed to Lee who after issuing orders that morning was not engaged with any of his commanders. British observer Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle wrote that during the “whole time the firing continued, he sent only one message and only received one report.” [19]

Meade wired Halleck that evening: “The enemy attacked me about 4 P.M. this day…and after one of severest contests of the war was repulsed at all points.” [20] However Meade, realized that caution was not a vice still needed to better assess the condition of his army, hear his commanders and hear from his intelligence service. He ended his message: “I shall remain in my present position tomorrow, but am not prepared to say until better advised of the condition of the army, whether operations will be of an offensive or a defensive character.” [21]

As Meade waited for his commanders his caution was apparent. Before McLaws’s attack on Sickles’ III Corps at the Peach Orchard Meade had asked his Chief of Staff Brigadier General Dan Butterfield to “draw up a contingency plan for withdraw to Pipe Creek.” During the attack on Sickles Alfred Pleasanton said that Meade ordered him to “gather what cavalry I could, and prepare for the retreat of the army.” [22] Some of his commanders who heard of the contingency plan including John Gibbon and John Sedgwick believed that Meade was “thinking of a retreat.” [23] Despite Meade’s assurances to Halleck, his army’s position had been threatened, but they were now solidly held. It is possible that some of his subordinates believed, maybe through the transference of their own doubts, that Meade “foresaw disaster, and not without cause.” [24]

In assessing Meade’s conduct it has to be concluded that while he had determined to remain, that he was smart enough to plan of the worst and to consult his commanders and staff in order to make his decision. Meade wrote to his wife that evening “for at one time things looked a little blue… but I managed to get up reinforcements in time to save the day….The most difficult part of my work is acting without correct information on which to predicate action.” [25]

Meade met with Colonel George Sharpe from the Bureau of Military Information along with Hancock and Slocum at the cottage on the Taneytown Road where he made his headquarters. Sharpe and his aide explained the enemy situation. Sharpe noted “nearly 100 Confederate regiments in action Wednesday and Thursday” and that “not one of those regiments belonged to Pickett.” He then reported with confidence that indicated that “Pickett’s division has just come up and is bivouac.” [26]

It was the assurance that Meade needed as his commanders came together. When Sharpe concluded his report, Hancock exclaimed, “General, we have got them nicked.” [27]

At about 9 P.M. the generals gathered. Present were Meade, and two of his major staff officers Warren just back from Little Round Top, though wounded and tired, and Butterfield, his Chief of Staff. Hancock, now acting as a Wing Commander was there with John Gibbon, who was now commanding II Corps, Slocum of XII Corps with Williams. John Newton a division commander from VI Corps who had just arrived on the battlefield had been appointed to command I Corps and was present along with Oliver Howard of XI Corps. John Sedgwick of VI Corps, George Sykes of V Corps, and David Birney, now commanding what was left of the wounded Dan Sickles’ III Corps made up the rest. Alfred Pleasanton was off with the cavalry and Henry Hunt was attending to the artillery.

The meeting began and John Gibbon noted that it “was at first very informal and in the shape of a conversation….” [28] The Army’s condition was discussed and it was believed that now only about 58,000 troops were available to fight. Birney honestly described the condition of III Corps noting that “his corps was badly chewed up, and that he doubted that it was fit for much more.” [29] Newton who had just arrived was quoted by Gibbon as saying that Gettysburg was “a bad position” and that “Cemetery Hill was no place to fight a battle in.” [30] Newton’s remarks sparked a serious discussion, in which Meade asked the assembled generals “whether our army should remain on that field and continue the battle, or whether we should change to some other position.” [31]

Their reactions to the question showed that the army commanders still had plenty of fight in them. Meade listened as his generals discussed the matter. Hancock said he was “puzzled about the practicability of retiring.” [32] Newton later noted that he made his observations about the battlefield based on his belief that Lee might turn the Federal left and impose his army between it and its supplies, as Longstreet However Newton and the other commanders agreed that pulling back “would be a highly dangerous maneuver to attempt in the immediate presence of the enemy.” [33]

Finally, Dan Butterfield, no friend of Meade who was one of the McClellan and Hooker’s political cabal who Meade retained when he took command posed three questions to the assembled generals:

“Under existing circumstances, is it advisable for this army to remain in its present position, or retire to another nearer its base of supplies?

It being determined to remain in present position, shall the army attack or wait the attack of the enemy?

If we wait to attack, how long?” [34]

Gibbon as the junior officer present said “Correct the position of the army…but do not retreat.” Williams counseled “stay,” as did Birney and Sykes, and Newton, who after briefly arguing the dangers finally agreed. Oliver Howard not only recommended remaining but “even urged an attack if the Confederates stayed their hand.” Hancock who earlier voiced his opinion to Meade that “we have them nicked” added “with a touch of anger, “Let us have no more retreats. The Army of the Potomac has had too many retreats….Let this be our last retreat.” Sedgwick of VI Corps voted “remain” and finall, Slocum uttered just three words “Stay and fight.” [35]

None of Meade’s assembled commanders counseled an immediate attack, and all recommended remaining at least another day. When the discussion concluded Meade told his generals, “Well, gentlemen…the question is settled. We remain here.” [36]

Some present believed that Meade was looking for a way to retreat to a stronger position, that he had been rattled by the events of the day. Slocum believed that “but for the decision of his corps commanders” that Meade and the Army of the Potomac “would have been in full retreat…on the third of July.” [37] Meade denied such accusations before Congressional committees the following year as Radical Republicans in Congress sought to have him relieved for political reasons.

Much of the criticism of Meade’s command decisions during the battle were made by political partisans associated with the military cabal of Hooker, Butterfield and Sickles, as well as Radical Republicans who believed that Meade was a Copperhead. Both Butterfield and Birney accused Meade before the committee of wanting to retreat and “put the worst possible interpretation on Meade’s assumed lack of self-confidence without offering any real evidence to substantiate it.” Edwin Coddington noted “that Meade, other than contemplating a slight withdraw to straighten his lines, wanted no retreat from Gettysburg.” [38]

Alpheus Williams of XII Corps, wrote to his daughters on July 6th regarding his beliefs about Meade on the night of July 2nd. “I heard no expression from him which led me to think that he was in favor of withdrawing the army from before Gettysburg.” [39] Likewise, the message sent by Meade to Halleck indicates Meade’s own confidence in the upcoming battle of July 3rd. If Meade had some reservations during the day, as he mentioned in the letter to his wife, they certainly were gone when he received the intelligence report from Sharpe and heard Hancock’s bold assertion that the enemy was “nicked.”

As the meeting broke up shortly after midnight and the generals returned to their commands Meade pulled Gibbon aside. Gibbon with his II Corps held the Federal center on Cemetery Ridge. Meade told him “If Lee attacks tomorrow, it will be in your front.” Gibbon queried as to why Meade thought this and Meade continued “Because he has made attacks on both our flanks and failed,…and if he concludes to try it again it will be on our center.” Gibbon wrote years later, “I expressed the hope that he would, and told General Meade with confidence, that if he did we would defeat him.” [40]

If some of his generals and political opponents believed Meade to be a defeatist, but defeatism of any kind was not present in his private correspondence. He wrote to his wife early in the morning of July 3rd displaying a private confidence that speaks volumes: “Dearest love, All well and going on well in the Army. We had a great fight yesterday, the enemy attacking & we completely repulsing them- both armies shattered….Army in fine spirits & everone determined to do or die.” [41]

The contrast between Lee’s and Meade’s decision-making process was that Meade did what Lee should have done. He was active on the battlefield, he consulted his intelligence service, and he consulted his commanders on the options available to him. Lee remained away from the action on July 2nd he failed to consult his commanders. Lee failed to gain accurate intelligence on the Federal forces facing him, and he failed to fully take into account his losses. Meade better demonstrated the principles of what we now call “mission command.” Lee’s vaunted leadership and operational abilities were absent throughout the Gettysburg campaign, but never so much as from the 1st to the 3rd of July, 1863.

Notes

1 Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee’s Lieutenant’s a Study in Command, One volume abridgement by Stephen W Sears, Scribner, New York 1998 p.558

2 Lee, Robert E, Reports of Robert E Lee, C.S. Army, Commanding Army of Northern Virginia Campaign Report Dated January 20th 1864. Amazon Kindle Edition location 594 of 743

3 Freeman, Douglas S. R.E. Lee volume 3 Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York 1935 p.150

4 Sears, Stephen W Gettysburg Houghton Mifflin Company, New York 2003 p.349

5 Coddinton, Edwin Gettysburg, A Study in Command Simon and Schuster New York 1968 p.455

6 Trudeau, Noah Andre Gettysburg, A Testing of Courage Harper Collins, New York 2002 p.4117 Ibid p.412

8 Ibid. p.347

9 Ibid. p.430

10 Wert, Jeffry General James Longstreet, the Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier A Tuchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York 1993 p.283

11 Foote, Shelby The Civil War, A Narrative, Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.529 12 Ibid. Wert p.283

13 Ibid. Sears p.349

14 Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.377

15 Ibid. Foote p.531

16 Ibid. Wert p.287

17 Ibid. Freeman p.589

18 Ibid. Wert p.290

19 Fremantle, Arthur Three Months in the Southern States, April- June 1863 William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London 1863 Amazon Kindle edition p.266

20 Sears, Stephen W Gettysburg Houghton Mifflin Company, New York 2003 pp.341-342

21 Ibid. p.342

22 Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2013 p.355

23 Ibid.

24 Foote, Shelby The Civil War, A Narrative, Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p.524

25 Trudeau, Noah Andre Gettysburg, A Testing of Courage Harper Collins, New York 2002 p.413

26 Ibid. Sears p.342

27 Ibid. Trudeau p.413

28 Ibid. Sears p.342

29 Ibid. Trudeau p.415

30 Ibid. Guelzo p.556

31 Ibid. Guelzo p.556

32 Ibid. Sears p.343

33 Ibid. Sears p.343

34 Ibid. Trudeau p.415

35 Ibid. Guelzo p.556

36 Ibid. Foote p.525

37 Ibid. Guelzo

38 Coddinton, Edwin Gettysburg, A Study in Command Simon and Schuster New York 1968 pp.451-452

39 Ibid. p.452

40 Ibid. Foote p.525

41 Ibid. Trudeau p.345