The Complicated Lives of Those Who Return from War: Joshua and Fanny Chamberlain

Something Many Veterans and their Spouses Face Today

Fanny and Joshua Chamberlain (Mort Kunstler, 2002)

Over the 4th of July weekend, I spent a lot of time posting articles from my Gettysburg Staff Ride Text. One of them dealt with the human costs of war. Those costs are almost always in my mind when I read about Russia’s genocidal war against Ukraine, other bloody conflicts, or campaigns against ethnic or religious minorities in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. I have devoted much of my life to studying the history and the art and science of war. Contrary to what some might believe, such a study does not make one a warmonger unless they already are one in their heart. I agree with William Tecumseh Sherman, who wrote in a letter to the Mayor of Atlanta after capturing the city, “You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it…” Sherman’s words about war are true, as are the following words regarding those who bring about war, “and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out.”

War is a pestilence, a blight on humanity wrought by its need to profit from its need to subjugate others, enslave them in one form or another, and profit from their cruelty to others. Marine Corps General Smedley Butler famously wrote: “War is a racket. It is the only one international in scope. It is the only one in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives.” While Butler was talking about aggression against foreign lands, the comment applies to war called “civil wars,” including the American Civil War, which was launched by the southern states making up the Confederacy with the intent of preserving and expanding slavery, which was the most lucrative business in the United States when the war began.

While I wrote about the human costs of the American Civil War, I only briefly mentioned the physical, psychological, and spiritual costs; I didn’t mention how war affects the relationships between the survivors and their families. In the Staff Ride Text, I also covered that aspect, particularly Joshua Chamberlain and Gouverneur Warren, two of the heroes of Little Round Top. This account is about Chamberlain’s life after the war.

Joshua Chamberlain’s accolades at Little Round Top and at Petersburg were certainly earned, but others on that hill have been all too often overlooked by most people. The list includes Gouverneur Warren, who was humiliated by Phillip Sheridan at Five Forks, Strong Vincent, who died of wounds suffered on Little Round Top, and Paddy O’Rorke, the commander of the 140th New York of Weed’s Brigade on Vincent’s right, who was mortally wounded that day.

After the war like most citizen soldiers, Chamberlain returned to civilian life, and a marriage that was in crisis; and neither Joshua nor Fanny Chamberlain seemed able to communicate well enough to mend it. The troubled couple “celebrated their tenth wedding anniversary on December 7, 1865. He gave her a double banded gold-and-diamond bracelet from Tiffany’s, an extravagant gift that only temporarily relieved the stresses at work just below the surface of their bland marriage. Wartime separation had perhaps damaged it more than Chamberlain knew.” [1]

When he came home Chamberlain was unsettled. Fanny quite obviously hoped that his return would reunite them and bring about “peaceful hours and the sweet communion of uninterrupted days with the husband that had miraculously survived the slaughter” [2] and who had returned home, but it was not to be. Army life had given her husband a sense of purpose and meaning that he struggled to find in the civilian world. He was haunted by a prediction made by one of his professors. A prediction that “he would return from war “shattered” & “good for nothing,” [3] Chamberlain began to search for something to give his life meaning. He began to write a history of V Corps and give speeches around the northeast, and “these engagements buoyed his spirit, helping him submerge his tribulations and uncertainties in a warm sea of shared experience. [4] In his travels, he remained apart from Fannie, who remained with the children, seldom including her in those efforts. She expressed her heart in a letter in early 1866:

“I have no idea when you will go back to Philadelphia, why dont you let me know about things dear?….I think I will be going towards home soon, but I want to hear from you. What are you doing dear? are you writing for your book? and how was it with your lecture in Brunswick- was it the one at Gettysburg? I look at your picture when ever I am in my room, and I am lonely for you. After all, every thing that is beautiful must be enjoyed with one you love, or it is nothing to you. Dear, dear Lawrence write me one of the old letters…hoping to hear from you soon…I am as, in the old times gone bye, Your Fanny.” [5]

In the events that he spoke at with other veterans and their families, Joshua Chamberlain poured out his heart in ways that seemed impossible for him to do with Fanny. He spoke to the wives, parents, sons, and daughters at home who had lost those that they loved, not only to death:

“…the worn and wasted and wounded may recover a measure of their strength, or blessed by your cherishing care live neither useless nor unhappy….A lost limb is not like a brother, an empty sleeve is not like an empty home, a scarred breast is not like a broken heart. No, the world may smile again and repair its losses, but who shall give you back again a father? What husband can replace the chosen of your youth? Who shall restore a son? Where will you find a lover like the high-hearted boy you shall see no more?” [6]

Chamberlain then set his sights on politics, goal that he saw as important in championing the rights of soldiers and their well treatment by society. It was a laudable task, but, it was life that again interrupted his marriage to Fanny and brought frequent separation. Instead of the one term that Fanny expected, Chamberlain served four consecutive one-year terms as Governor of Maine and was considered for other political offices. However, the marriage continued to suffer and Fanny’s “protracted absence from the capitol bespoke her attitude toward his political ambitions.” [7] Eventually, Chamberlain returned home, and, “For twelve years following his last term as governor, he served as president of Bowdoin College, his alma mater. [8]

Chamberlain became a champion of national reconciliation admired by friends and former foes alike. However, he held bitterness towards some in the Union who he did not believe cared for his comrades or their families, especially those who had lost loved ones in the war. While saluting those who had served in the Christian and Sanitary Commissions during the war, praising veterans, soldiers, and their families, he noted that they were different than:

“Those who can see no good in the soldier of the Union who took upon his breast the blow struck at the Nation’s and only look to our antagonists for examples of heroism- those over magnanimous Christians, who are so anxious to love their enemies that they are willing to hate their friends….I have no patience with the prejudice or the perversity that will not accord justice to the men who have fought and fallen on behalf of us all, but must go round by the way of Fort Pillow, Andersonville, and Belle Isle to find chivalry worthy of praise.” [9]

However, Chamberlain never went out of his way to praise the 200,000 Black soldiers, the freemen, and former slaves who volunteered to fight for the Union. He supported emancipation as a military measure to end disunion. He came to believe that slavery was “repugnant to justice and freedom.” [10] But, he opposed “Enfranchising recently liberated slaves,” something that he believed, “should be decided by “the best minds of the South, and by no means by hasty and sweeping measures tending to give political preponderance to the most inferior.” [11]

Chamberlain’s post-war life, save for the times that he was able to revisit the scenes of glory and be with his former comrades was marred by deep personal and professional struggles and much suffering. He struggled with the adjustment to civilian life, which for him was profoundly difficult. He “returned to Bowdoin and the college life which he had sworn he would not again endure. Three years of hard campaigning however, had made a career of college teaching seem less undesirable, while his physical condition made a permanent army career impossible.” [12] The adjustment was more than even he could anticipate, and the return to the sleepy college town and the monotony of teaching left much to be desired.

These are not uncommon situations for combat veterans to experience, and Joshua Chamberlain, the hero of Little Round Top who was well acquainted with the carnage of war, suffered immensely. His wounds never fully healed and he was forced to wear what would be considered an early form of a catheter and bag. In 1868 he was awarded a pension of thirty dollars a month for his Petersburg wound which was described as “Bladder very painful and irritable; whole lower part of abdomen tender and sensitive; large urinal fistula at base of the penis; suffers constant pain in both hips.” [13] Chamberlain struggled to climb out of “an emotional abyss” in the years after the war. Part of the “abyss” was caused by his wounds which included wounds to his sexual organs, shattering his sexuality and causing his marriage to deteriorate.

He wrote to Fanny in 1867 about the “widening gulf between them, one created at least in part by his physical limitations: “There is not much left in me to love. I feel that all too well.” [14] Chamberlain’s inability to readjust to civilian life following the war, and Fanny’s inability to understand what he had gone through during it caused great troubles in their marriage. He “felt like hell a lot of the time, morose in mood and racked with pain.” [15] His wounds would require more surgeries, and in “April 1883 he was forced to have extensive surgery on his war wounds, and through the rest of the decade and well into the next he was severely ill on several occasions and close to death once.” [16]

By 1868 the issues were so deep that Fanny threatened him with divorce. She accused Joshua of domestic abuse, not in court, but among her friends and in town; a charge which he contested. It is unknown if the abuse actually occurred and given Chamberlain’s poor physical condition it is unlikely that he could have done what she claimed, it is actually much more likely, based on her correspondence as well as Fanny’s:

“chronic depression, her sense of being neglected if not abandoned, and her status as an unappreciated appendage to her husband’s celebrated public career caused her to retaliate in a manner calculated to get her husband’s attention while visiting on him some of the misery she had long endured.” [17]

The bitterness in their relationship at the time was shown in his offer to her of a divorce; a condition very similar to what many combat veterans and their families experience today. After he received news of the allegations that Fanny was spreading among their friends around town, Chamberlain wrote to her:

“If it is true (as Mr. Johnson seems to think there is a chance of its being) that you are preparing for an action against me, you need not give yourself all this trouble. I should think we had skill enough to adjust the terms of a separation without the wretchedness to all our family which these low people to whom it would seem that you confide your grievances & plans will certainly bring about.

You never take my advice, I am aware.

But if you do not stop this at once, it will end in hell.” [18]

His words certainly seem harsh, especially in our time where divorce, be it contested or uncontested does not have the same social stigma it did then. Willard Wallace wrote that the letter “reflects bewilderment, anger, even reproof, but not recrimination; and implicit throughout is an acute concern for Fanny, who did not seem to realize the implications of legal action. The lot of a divorcee in that era in a conservative part of the country was not likely to be a happy one.” [19] This could well be the case, but we do not know for sure his intent. We can say that it speaks to the mutual distress, anger, and pain that both Joshua and Fanny were suffering at the time.

The marriage endured a separation that lasted until 1871. When his final term as governor expired they reconciled, and the marriage did survive, for nearly forty more years. “Whatever differences may have once occasionally existed between Chamberlain and Fanny, the two had been very close for many years.” [20] Their reconciliation could have been for any number of reasons, from simple political expedience, in that he had been rejected by his party to be appointed as Senator, and the realization that “politics, unlike war, could never stir his soul.” [21] Perhaps, he finally recognized just how badly he had hurt her over all the years by neglecting her needs, and that her anger towards him was justified. But it is just as likely that deep in his heart he really did love her despite his chronic inability to demonstrate it in a way she could feel. Fanny died in 1905 and Chamberlain, who despite all of their conflicts loved her and grieved her, a grief “tinged with remorse and perhaps also with guilt.” [22] The anguished widower wrote after her death:

“You in my soul I see, faithful watcher, by my cot-side long days and nights together, through the delirium of mortal anguish – steadfast, calm, and sweet as eternal love. We pass now quickly from each other’s sight, but I know full well that where beyond these passing scenes you shall be, there will be heaven!” [23]

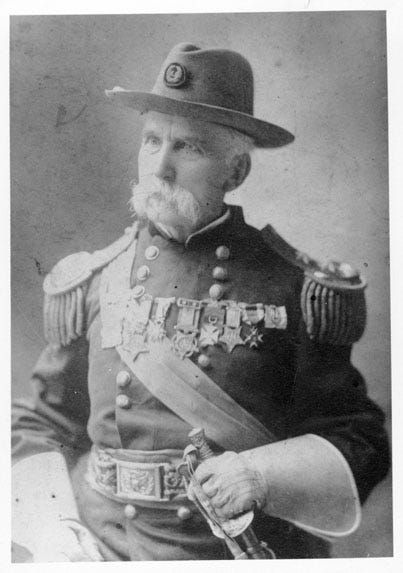

Joshua Chamberlain in about 1910

Chamberlain made a final trip to Gettysburg in May of 1913. He felt well enough to give a tour to a delegation of federal judges. However, “One evening, an hour or so before sunset, he trudged, alone, up the overgrown slope of Little Round Top and sat down among the crags. Now in his Gothic imagination, the ghosts of the Little Round Top dead rose up around him….he lingered up the hillside, an old man lost in the sepia world of memory.” [24] He was alone.

Joshua Chamberlain died on a bitterly cold day, February 24th, 1914, of complications from complications of the ghastly wound that he received at Petersburg in 1864. The Confederate minié ball that had struck him at the Rives’ Salient finally claimed his life just four months shy of 50 years since the Confederate marksman found his target.

Sadly, the story of the marriage of Joshua and Fanny Chamberlain is all too typical of many military marriages and relationships where a spouse returns home changed by their experience of war and struggles to readjust to civilian life. This is something that we need to remember when we encounter those changed by war and the struggles of soldiers as well as their families; for if we have learned nothing from our recent wars it is that the wounds of war extend far beyond the battlefield, often scarring veterans and their families for decades after the last shot of the war has been fired.

The Battle for Little Round Top which is so legendary in our collective history and myth was in the end something more than a decisive engagement in a great battle. It was something greater and larger than that. The battle was the terribly heart-wrenching story of ordinary, yet heroic men like Strong Vincent, Joshua Chamberlain, Gouverneur Warren, Paddy O’Rorke; and their families whose lives were changed forever on that day. As Chamberlain, ever the romantic, spoke about that day when dedicating the Maine Monument in 1888; about the men who fought that day and what they accomplished:

“In great deeds, something abides. On great fields, something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear; but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls… generations that know us not and that we know not of, heart-drawn to see where and by whom great things were suffered and done for them, shall come to this deathless field, to ponder and dream; and lo! the shadow of a mighty presence shall wrap them in its bosom, and the power of the vision pass into their souls.” [25]

Notes

[1] Golay, Michael. To Gettysburg and Beyond: The Parallel Lives of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and Edward Porter Alexander Crown Publishers Inc. New York 1994. p.282

[2] Smith, Diane Monroe Fanny and Joshua: The Enigmatic Lives of France’s Caroline Adams and Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain Thomas Publications, Gettysburg PA 1999. p.182

[3] Smith, Fanny and Joshua p.180

[4] Longacre, Edward Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man Combined Publishing Conshohocken PA 1999. p.260

[5] Smith, Fanny and Joshua pp.178-179

[6] Smith, Fanny and Joshua p.181

[7] Longacre Joshua Chamberlain p.261

[8] LaFantasie, Glenn W. Twilight at Little Round Top: July 2, 1863 The Tide Turns at Gettysburg Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2005 p.245

[9] Smith, Fanny and Joshua p.180 It is interesting to note that Chamberlain’s commentary is directed at Northerners who were even just a few years after the war were glorifying Confederate leader’s exploits. Chamberlain instead directs the attention of his audience, and those covering the speech to the atrocities committed at the Fort Pillow massacre of 1864 and to the hellish conditions at the Andersonville and Belle Isle prisoner of war camps run by the Confederacy.

[10] Longacre, Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man. p.27

[11] Longacre, Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.264

[12] Wallace, Willard. The Soul of the Lion: A Biography of Joshua L. Chamberlain Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg PA 1960 p.203

[13] Golay, To Gettysburg and Beyond p.289

[14] Longacre Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.259

[15] Golay, To Gettysburg and Beyond p.288

[16] Longacre Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.285

[17] Longacre Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.268

[18] Chamberlain, Joshua L. Letter Joshua L. Chamberlain to “Dear Fanny” [Fanny Chamberlain], Augusta, November 20, 1868 retrieved from Bowdoin College, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain Documents http://learn.bowdoin.edu/joshua-lawrence-chamberlain/documents/1868-11-20.html 8 November 2014

[19] Wallace, The Soul of the Lion p.227

[21] Wallace, The Soul of the Lion p.297

[22] Longacre Joshua Chamberlain: The Soldier and the Man p.290

[23] Chamberlain, Joshua L. Bayonet! Forward, My Civil War Reminisces. Butternut and Blue, Limited, 1994 p.170

[24] Golay To Gettysburg and Beyond pp.342-343

[25] Chamberlain, Joshua Lawrence. Chamberlain’s Address at the dedication of the Maine Monuments at Gettysburg, October 3rd 1888 retrieved from http://www.joshualawrencechamberlain.com/maineatgettysburg.php 4 June 2014

What an extensive and well-documented piece. It's reflective of the tribulations of marriage and the complexity of blending two lives. As a veteran of a soon to be 50-year marriage to a successful and ego-driven man, I can attest to the destructive power of loneliness and disappointment.

My husband was intent on pursuing a career in politics and in fact, we were active on the campaign circuit from the time we met in high school. We were signing up unregistered, minority voters even before we were age-eligible to vote ourselves. Harry participated in "Freedom Summer" in 1964, the year that three civil rights workers were kidnapped and murdered in Mississippi.

Ultimately we married after each of us graduated from college, and Harry had already completed a Master's Degree in Journalism. After all the excitement of the Protest Moment, we settled down,. we Harry moped about his lack of. ...whatever.

I admire the fact that Fanny pursued her husband and even when to the extreme option of threatening to sue him for divorce (unheard of in those days)!

It took every ounce of connivance on my part to get my husband off the couch of self-pity: a ticket for the Law School Aptitude Test (LSAT), for his 26th birthday was my strategy.. He scored well and was accepted into a 4-year night law school (St. John's, the very school my father and his had graduated from decades before)

! But did I sit back and wait for the money to roll in? What a waste of time that would have been. I understand that many marriages fail when the man is preoccupied in law or medical school and so I decided to attend class (in the back, unacknowledged. Now I could be pro-active and didn't have to worry about being sidelined by his anticipated, brilliant career.

In fact, we both enjoyed law school (and his study group; likewise had spouses of both stripes (male and female), and we suddenly had a network of social and intellectual merit! We even studied abroad in Jerusalem in the summer of 1976 (I was 7 months pregnant, and it was just after the hostage-battle at Entebbe Airport)!

I'm not suggesting the old cliche of a strong woman behind every powerful man. I am advocating that you have to stand up and respect yourself! And don't sweat the small stuff, because War may be Hell, but Marriage is no Bed of Roses!

The haunted life of a soldier returned from war