The Congressman Who Killed a Man Across from the White House and Got Away with It, Part Three: Trial of the Century

Today we continue with the story of America’s incredible scoundrel, Dan Sickles. In the first two pars we explored his early life and career, followed by his election to Congress in 1856. It was after his re-election in 1858 and return to Washington D.C. in 1859 that he shot Philip Barton Key, who had been conducting a very open affair with Sickles’ wife Teresa, in Lafayette Square across from the White House. Sickles turn himself in to the Attorney General and awaited, trial in Washington D.C.’s jail.

This is the story of that trial, which was the first to be broadcast across the nation and the world through the use of the telegraph. At the end of the day reporters would send their stories to newspapers around the country where an eager public waited to read them. Never before had this happened and it set a precedent for other trials to emulate through radio, television, and now the internet. It showed the eternal truth said in song by the late Don Henley, “Give us dirty laundry.” Such trials as the Scopes Monkey Trial, the McCarthy Hearings, the O.J. Simpson trial, the impeachments of Bill Clinton and Donald Trump, not to mention the trials of numerous celebrities have transpired since the Sickles trial, but few matched it for its drama and the country's sympathy for the defendant.

I went back to re-read and include some of the contemporaneous newspaper accounts in this revision of my original. Going back to them years after reading them the first time was quite fascinating.

As Sickles was being transported to jail, the Coroner’s investigation of the murder proceeded at the Club House, where Key’s body was taken. Witnesses testified to the shooting, and Sickles’s friend Butterworth refused to answer questions about what he knew, simply saying that because it was a coroner’s inquest. “It is sufficient to state simply that Mr. Sickles shot Mr. Key, who fell dead.” [1] the Coroner concurred. The next day a Grand Jury was convened, and on March 24th, Sickles was indicted, and a trial date was set for April 4th, 1859. [2]

The stage was now set for one of the most unbelievable and storied trials in American history. It was a trial that would have been much more suited to the era of 24/7 cable news coverage and the Internet than the era of the telegraph and newspaper, but even so, it was sensational by any standard. It riveted the public's attention in every part of the nation, from the largest cities to the smallest towns.

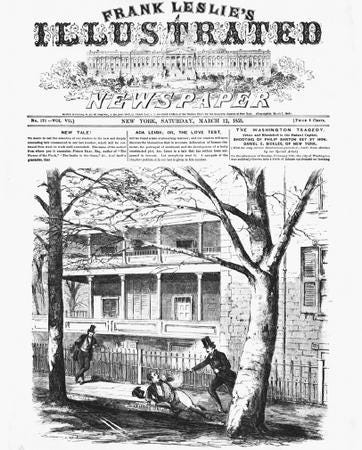

Almost immediately, swarms of journalists were camped outside the prison and Sickles’ house, where distraught Teresa sought a way to gain Dan’s forgiveness, having received his broken wedding band, which he sent to her from the jail. Witnesses to her dalliances with Key at the 15th Street house and other venues were brought to the Stockton Mansion to identify her. “She was the meat in the market, the ogre at the carnival. A little way across the square, souvenir hunters were cutting fragments of wood out of the tree by which Key had fallen, and artists from the illustrated papers set up their easels and began sketching every aspect of the area – the railings, the Stockton Mansion, the Clubhouse.” [3] A Presbyterian pastor who knew the couple found her obsessed by the shame that she had brought upon herself and her daughter, and he “found her in such mental agony that he feared for her sanity and even felt that she might try to take her life.” [4]

It was a credit to her emotional strength that Teresa survived the ordeal she had helped to bring about and which she found herself blamed for, even by her father, who felt that she had dishonored the Bagioli family name. Antonio Bagioli wrote to Dan in prison, “You have heaped on my child affection, kindness, devotion, generosity. You have been a good son, a true friend, and a devoted, kind, loving husband and father.” [5] Of all the commentators, it was the eminent historian and diplomat George Bancroft who seemed to have any “sense of Teresa’s pain: “Poor child, what a cruel thing to deprive her of her sole stay and support. Key was the only man she could look to for sympathy and protection.” [6]

After Barton Key’s lifeless body was borne off in a mahogany casket to the Presbyterian cemetery in Baltimore and buried in the grave of his dead wife, and his children placed in the care of his family, his effects, what they amounted to, including his resplendent Montgomery Guards uniform were “sold off to a morbid, bargain-hunting, souvenir-hounding crowd.” [7] It was an ignoble end to the scandalous story of the son of Francis Scott Key, a story that soon, with all of its salacious detail, would be revealed to the public.

Meanwhile, inside the jail, her husband endured some of the worst conditions in Washington. The jail, known as the “Blue Jug,” was long considered due for replacement and was long deemed unfit for use, and Congress had considered condemning it for over a decade. “The Jug was badly overcrowded with petty grifters, runaway slaves, and violent criminals, as many as twelve to a cell, locked away to rot. He could hear their cries bounce off the dark walls as if they were already in Hell.” [8]

alternating between fits of rage and calm was visited by Washington’s Mayor James Barret, Sam Butterworth, Attorney General Black, Vice President John C. Breckinridge, and Speaker of the House, James Orr. He was comforted by the many expressions of support and sympathy found in scores of letters from people around the country, one of the first “a kindly note from the President” [9] and others from total strangers. Friends and allies from New York and Washington also joined him. “James Topham Brady, John Graham, and Thomas Francis Meagher, able lawyers all, arrived post haste to defend their rash ally” [10] as well as his father who, before offering encouragement to his son, offered a sharp chastisement, “You hot-headed fool! That’s no way to settle things! No woman’s worth it! No matter how you come out of this, you’ve killed your career – White House and everything else.” [11] Undeterred and calm, Dan told his father that he understood and that if he had to, he would do it again, after which his father began to discuss the organization of his son’s defense with this legal team.

The case was front-page news in all the major newspapers, which provided “extensive coverage of the “Sickles Tragedy.” Sickles’ murder of his friend Key in broad daylight in view of the White House had all of the scandalous elements that have thrilled Americans then and even today: “adultery, politics, celebrity, and a handsome corpse,” [12] not to mention a beautiful young woman who even more than her husband who had killed a man, stood accused in the eye of the public. The Louisville Daily Courier noted, “This dreadful affair is the theme of conversation in every social community in the country. No event of a similar kind in our remembrance has excited so much comment.” [13]

Despite the notoriety of the case, many people found sympathy with Sickles and believed that no jury would convict him of murder or manslaughter. After all, Teresa was the one who committed adultery with Key. The New York Herald “doubted that a grand jury would indict him. Even if he were indicted, Harper’s Weekly presumed that no jury would convict him of manslaughter if the adultery charge were proven, which it considered a foregone conclusion.” [14] The New York Times noted well before the trial opened, “there appears to be no second opinion as to the certainty of Mr. Sickles acquittal” but “national interest” arose from “the general desire to see the whole case fairly put, and the million scandals of mystery laid to rest by the plain facts.” [15] Newspapers like the New York Evening Post, his political arch-enemy found the murder an excellent opportunity to attack Sickles, “That wretched man, Daniel E. Sickles, has in his career reached the stage of assassination, and dipped his hands in human blood… It is certain that a man… who in his own practice, regards adultery as a joke and the matrimonial bond as no barrier against the utmost caprice of licentiousness – has little right to complain when the mischief which he carriers without scruple into other families enters his own.” [16] But such commentary was the exception, and it came from the organ of a political enemy.

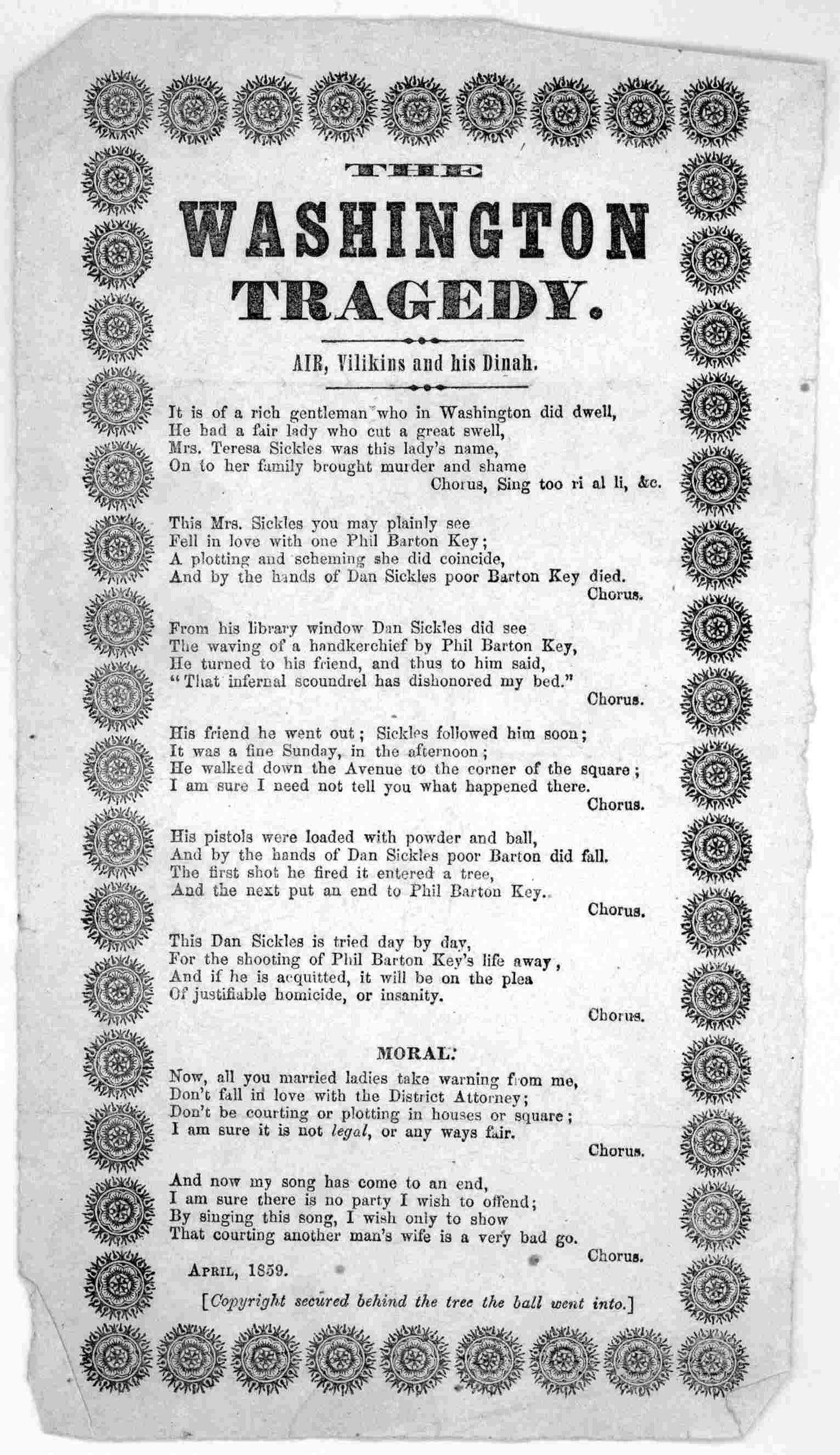

It is an interesting comment on the era in that a woman’s adultery, even when committed by the wife of an adulterous male who had killed her lover, was considered more of a social stigma and crime than murder. People who had been her friends and confidants and who had enjoyed her hospitality raced to see how far they could distance themselves from her, often demeaning her status in Washington society. Songs and poems were published warning women not to engage in her behaviors. William Stuart, the Washington correspondent of the New York Times, attempted to correct the vile comments hurled at her, wrote Teresa:

“certainly did move in the best society, and was generally courted and adored. The idea that she filled a doubtful position in Washington is preposterous. Why is it that poor human nature so loves to shove downhill with accelerated motion every sinning fellow-creature who once is found failing?” [16]

Within days Sickles had assembled one of the most formidable defense teams ever to dominate an American court. Brady, who was considered to be the ablest criminal defense lawyer of his day became the lead attorney for the defense team, and was joined by Sickles’ New York friends, John Graham and Thomas Meagher. Brady was an excellent choice, he “was admired and even loved by society in general, but on top of that, though his legal repertoire was wide, he had been involved successfully in more than fifty murder cases.” And he “had also made a special study of pleas of insanity,” [17] something that would figure greatly in the trial.

Additionally, President Buchanan helped recruit one of the finest attorneys in the country, the future Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton to the team. They were joined by four lesser known, yet high-powered attorneys; Samuel Chilton a Virginian who later represented John Brown, and his partner Allen Magruder, Daniel Ratcliffe, and Philip Phillips, a former Alabama Congressman and member of Washington’s Jewish community. Additionally, Reverdy Johnson, one of the most respected attorneys of the day served as an occasional advisor. “The Washington Evening Star observed that Sickles was collecting a lot of lawyers for a man whose defenders did not expect to leave their box before acquitting him.” [18]

Sickles’ defense team was a nineteenth-century legal Dream Team against which the government deployed but one attorney, Key’s former assistant District Attorney Robert Ould. Ould, described by one of Sickles’ biographers as “a dull bull of a man, at one time a Baptist parson,” [19] had been named acting District Attorney by President Buchanan when Key was killed. It was an odd place for Ould, as he was serving to prosecute his former boss’s killer, at the behest of the President, who happened to be one of the defendant’s best friends. Ould, the former parson “was placed by inference in the unhappy position of defending adultery – something that he indignantly denied, insisting that he was merely prosecuting a killer….” [20] but to many people, the murderer of an adulterer by an aggrieved husband was complete justified. The defense dream team totally outclassed Ould, and Key’s family paid to have John Carlisle a respected Washington attorney to aid him in the case, but the trial would prove them appear incompetent and not up to the task of convicting Sickles.

The defense team met with Sickles in the fetid squalor of the jail with prisoners shrieking and wailing in the background they elected to skip the preliminary hearing, which meant that Sickles would have to remain incarcerated until his trial. In part this was due to threats against Sickles’s life should he be released, and because he was in jail, his case would be at the top of the docket. [21] They decided to push for a speedy trial and decided, as many lawyers do today. They also decided to try the case in the newspapers, which in light of the lurid nature of the story hung on every word coming out of Washington made it ripe for consumption by an obsessed country.

The defense team pursued the strategy of “entirely reversing the roles of Sickles and Key by putting the dead man on trial for having made a victim of the defendant, and the New York Press prepared the public for just such an emotional appeal.” [22] The news stories printed by papers that supported Sickles as well as those of his detractors helped inflame the public as the newspapers across the country “wherever wires ran, were front-paging the story under screaming headlines and, in larger cities, rushing out extras every hour or two, as fresh details came to hand.” [23]

On March 8th, 1859, the Washington Evening Star published editorials from multiple papers that had weighed in on the case. The Columbia, South Carolina Carolinian wrote:

“As far as we can judge, public sentiment fully sustains Mr. Sickles. This is natural. We would pity a public sentiment that is so lost to the sanctimony of family relation as to denounce an infamous murder that which, terrible though it be, was but a proper punishment for so heinous an offense. The man stands as the head of his family; he is its protector and governor; and upon him, the head of the household government, rests the vindication of such infamy and disgrace as may be brought upon it by conduct such as that as Mr. Key has been guilty… it augurs well for the public sentiment of our country that, with a few exceptions, even though it be the shedding of blood, this act meets with full approval, and with a generosity which, we hope, will ever characterize the American people. Instead of being the object of denunciation, Mr. Sickles receives the most cordial sympathy.”

The editors of the New York Examiner condemned Sickles:

“In our paradise of snobs, too true, it is impossible to bring a “gentleman” to trial for anything he many do, and we can scarcely look for such a miracle of justice as the punishment of Mr. Sickles under the circumstances. But we do hope that the public opinion of the public and the press will not be debauched sympathetically in the orgies of Revenge, and made to bow before that bloody idol. In the name of Christianity, we owe a protest against the current sympathy with men of blood. We must not uphold them by the faintest extenuation, in any circumstances. Mr. Sickles has gratified his passions, but he has executed no justice, even though it had been province to do it, in thus punishing one party to a mutual crime…” [24]

Newspapers in Europe fed the insatiable craving for news of the murder. The London Examiner wrote: “Murder in America has not only its apologists but its admirers. We have long been struck with the theatrical turn which crime takes in the United States. When an American sets about a murder he prepares his part as for a scene in a drama.” [25]

The private affairs of Dan and Teresa Sickles became known around the nation, and and around the world, even though the judge in the case refused to admit the confessions Sickles had forced from Teresa into evidence they found their way into the papers, like Harper’s not only ran the text but reproduced the confession in enlarged facsimile form. The question in many people’s mind “was Dan Sickles justified in slaying the man who had betrayed his confidence and seduced his wife?… As a consequence, the whole country turned jury.” [26]

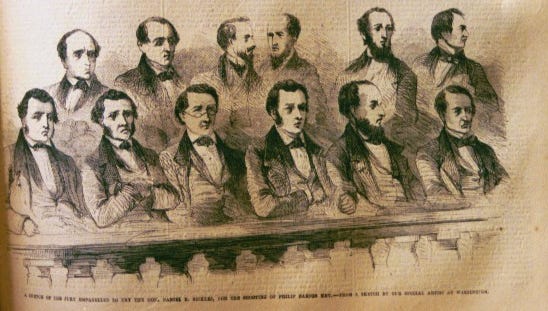

The trial began on April 4th, 1859, just over a month after the killing and barely a week after the indictment was handed down. The first three days involved jury selection, a task that the defense turned over to Philip Phillips, who sparred with the prosecutor Ould over the twelve men who would eventually sit in judgment of Dan Sickles. Ould attempted to gain a favorable jury by introducing the property qualifications of jurors, he “ruled out jurors who did not meet the requirement of owning property valued at $800. Since this $800 property limit had not been imposed in similar cases, Ould’s insistence on it would attract much scorn from Dan’s lawyers…”[27] Philips fought back, embarrassing Ould in the process, but not getting the judge to change his narrow application of the law to help the defense. Over two hundred potential jurors were examined before twelve unbiased jurors could be found, and a “great majority of those dismissed confess strong prejudice in favor of the prisoner.” [28] When the jury was seated, it was composed of twelve men, two farmers, four grocers, a merchant, a tinner, a coach maker, a men’s clothing salesman, a shoemaker, and a cabinetmaker, “but not a single “gentleman” in the occupational sense.” [29]

Ould opened his case, and “ponderously, powerfully, in the blackest of terms,” [30] he drew a picture of the killing. He delivered an “emotionally charged argument that Sickles, “a walking magazine,” had taken deliberate care in arming himself against Key, who only had “a poor and feeble opera-glass.” [31] Ould argued “that homicide with a deadly weapon, perpetrated by a party who has all the advantage on his side and with all the deliberate cruelty and vindictiveness, is murder, no matter what the antecedent provocation in the case.” [32] He then called twenty-eight witnesses, most of whom had witnessed the shooting, but he did not call upon Butterworth, Teresa, or the young White Clerk who had told President Buchanan and been sent away. Likewise, he had not established intent, a key factor in any murder trial, nor had he introduced evidence he had obtained regarding Sickles’ affairs with women in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and elsewhere. The presentation of the physical evidence of Barton Key’s clothing and the bullet that supposedly killed Key was botched. The bullet the prosecution claimed killed to kill Key did not fit either the Derringer or the Colt revolver. [33] Thus, Ould left open for the defense the chance to explore all the salacious details of the case to put Key on trial and to establish exculpatory reasons why Sickles had killed Key. Ould’s presentation of his case was brief and so futile “that it seemed that Key was on trial for seduction, not that Sickles was on trial for murder.” [34]

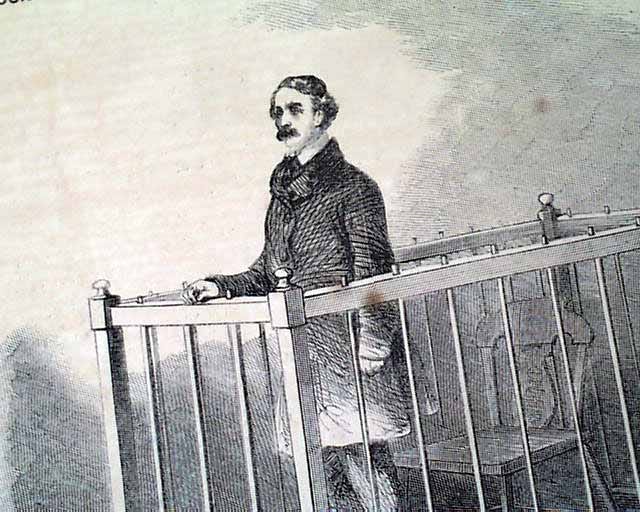

As Sickles stood in the dock, his defense team made mincemeat of the prosecution. John Graham’s opening statement was a work of oratory genius that “would massively outshine Robert Ould’s more cumbersome opening.” [35] Weaving allusions from Shakespeare and other literary greats into his statement, he painted Sickles as the victim of an adulterous rogue who had, on a Sunday, a day when he should have “sent his aspirations heavenward,” had instead besieged “that castle where for security and repose the law had placed the wife and children of his neighbor.” [36] Casting Sickles as the aggrieved and temporarily insane victim, he asked if it was a “crime for a husband to defend his family altar.” From there, he proceeded to use quotes from Shakespeare’s Othello he inveighs against the adulterer as the supreme criminal, piling up quotation upon a quotation from the Old Testament and Roman law to show that in wiser days, the punishment invariably was death’” [37] to paint the picture of Sickles’ agony as he saw the man who had defiled his wife prowling outside of his home. Graham turned the case from one against Sickles to Philip Key.

“A few weeks since the body of a human being was found in the throes of death in one of the streets of your city. It proved to be the body of a confirmed and habitual adulterer. On a day too sacred to be profaned by worldly toil - which he was forbidden to moisten his brown with the sweat of honest labor - on a day when he should have risen above the grossness of his nature, and though on no other days had he sent his aspirations heavenward, he should have on that day have allowed them to pass in that direction, we find him besieging with the most evil intentions that castle for their security and repose the law had placed the wife and children of his neighbor… Had the deceased observed the solemn precept, “Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy,” he might this day have formed one of the living. The injured husband and father rushes on him in the moment of his guilt and, under the influence of a frenzy, executes on him a judgment as which was as just as it was summary.” [38]

Graham then went to provocation and argued that due to the circumstance of the crime, a friend and confidant attempting to defile Sickles’ wife on a Sunday, the prosecution “needed to prove Dan’s sanity at the time of the act. And they could not do that, because there was not enough in the case “to melt the heart that is not cut from the unwedgeable gnarled oak.” [39] It was a masterful performance.

Graham brought up the crux of his argument for Sickles, that Sickles had killed Key in a moment of temporary insanity.

“The question which I present to your mind is this: [when] a man receives provocation which excites in him an amount of frenzy which he cannot control,” is he “responsible for what he does under the influence of that frenzy? It is folly to punish a man for what he cannot help doing, if you concede that the transport is such that he cannot control it. You cannot make him criminally responsible for what he does under the influence of that transport… We mean to say, not that Mr. Sickles labored under insanity in consequence of an established mental permanent disease, but that the condition of his mind at the time of the commission of the act in question was such as would render him legally unaccountable, as much so as if the state of his mind had been produced by a mental disease.” [40]

Over the next two weeks, Brady, Stanton, and Graham continued to hammer the prosecution case. The defense proved that Key’s family had tampered with evidence, including testimony from a locksmith who had changed the locks at the 15th Street house at the direction of Key’s family. Witness after witness was introduced to undermine the prosecution and support the defense’s claim that Sickles’ was indeed in a state of uncontrollable madness, and the defense deftly parried the prosecutor’s rebuttal witnesses. When Ould attempted to keep African American witnesses from testifying Stanton, thundered and“accused the prosecution of a “monstrous” attempt to suppress evidence in its zeal of the defendant’s blood,” [41] and argued from North Carolina precedent that the prosecution was not willing to grant Sickles the same right as a slave. As his lawyers argued his case and witnesses gave testimony Sickles maintained his composure except for a number of times when he broke down and had to be excused from the proceedings. “Whether the courtroom histrionics were real or an award-winning performance, the jury witnessed firsthand a husband who was mentally unable to bear his wife with another man.” [42] On the Friday, April 22nd, Judge Crawford declared the testimony closed and the next day began the closing arguments.

Saturday, April 23rd dawned with a violent gale, but that did not prevent crowds of people from trying to gain admittance to the courtroom. Edwin Stanton began the defense closing arguments in a manner that was calm and precise. He brought up that justifiable homicide included that which was “committed in defense of family chastity, the sanctity of the marriage bed, the matron’s honor, the virgin’s purity.” [43] Stanton continued:

“The death of Key was a cheap sacrifice to save one mother from the horrible fate, which on that Sabbath day, hung over this prisoner’s wife and the mother of his child. You may also plant on the best and surest foundations the principles of law which secure the peace of the home, the security of the family, and the relations of husband and wife, which have been in the most horrid manner violated in this case.” [44]

Since the prosecution had never brought into evidence Sickles’ own violation of these covenants his attacks on Key and the prosecution case hit home. As he continued his voice rose to a roar, sounding like a prophet of ancient Israel “Who seeing this thing, would not exclaim to the unhappy husband, “Hasten, hasten, to save the mother of your child! And may the Lord who watches over the home and family guide the bullets and direct the stroke!” [45] When Stanton finished the court erupted in a frenzy as spectators as well as supporters of Sickles applauded his closing. [46]

Next up was Brady who went on for three hours, captivating the audience which hung on every word. “When Daniel Sickles realized how he had been betrayed, all the emotions of his nature changed into a single impulse; every throb of his heart brought before him the sense of his great injuries; every drop of his blood was burdened with a sense of shame; he was crushed by inexorable agony in the loss of his wife, in the dishonor that he had come upon his child, in the knowledge that the future – which had opened to him so full of brilliancy – had now been enshrouded in eternal gloom by one who, contrawise, should have invoked form the eternal God his greatest effulgence on the path of his friend….” [47]

The closing had been masterful, emotional, and dramatic. In response Ould attempted to recover, but his arguments were weak, he agreed with the defense about the crime of adultery, and attempted to redirect the jury’s attention that it was Sickles who was on trial for murder and not Key for adultery, but he had already lost that argument. He called the defense of temporary insanity a ploy and “mentioned how easily, and readily a man on trial for his life might pretend to be deranged if he were on trial for his life.” But it was too little, too late. Since there was no psychiatric profession to weigh in on the matter, the argument of temporary insanity fell back on the “tradition of male marital dominance” and “that argument played well among men who rarely wore collars on their shirts…” [48] the very kind of men seated in the jury booth. When the jury recessed to deliberate Sickles’ fate on the 26th it took them less than an hour to return their verdict, and few were surprised when it came back “not guilty.”

When the jury Forman uttered the words “Not guilty.” What followed was minutes of “unparalleled uproar,” hundreds yelling “as though gone mad, others wept,” as people leapt into the prisoner’s box to embrace Sickles.” [49]

Stanton “was so excited that he did a jig in the courtroom, the hoarsely called for three cheers.” [50]As he did “Pandemonium and cheers broke out in the courtroom.” [51] People crowded around to congratulate Sickles and the crush was so great that Sickles had to be escorted for the courtroom. President Buchanan on hearing the verdict was delighted, later in the evening, though he sought rest, Sickles was taken by Brady to a gala in his honor attended by nearly 1500 supporters and well-wishers. The revealers were accompanied by the Marine Corps Band which serenaded them, the prosecutors, and Sickles who had by now retired to his hotel room. The trial was over but the trials of Dan Sickles were not.

To be continued…

Notes

[1] DeRose, Chris. Star Spangled Scandal: Sex, Murder, and the Trial that Changed America. Regnery History, Washington, D.C. 2019 p.90

[2] DeFontaine, Felix. The Trial of the Hon. Daniel E. Sickles for Shooting Philip Barton Key, Esq., U.S. District Attorney for Washington, D.C., February 27th, 1859. R.M. DeWitt Publisher, New York, NY. 1859

[3] Keneally, Thomas American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles Anchor Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2003 p.142

[4] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible copyright by the author 1958 and 1984 Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg PA p.63

[5] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel p.146

[6] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel p.147

[7] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and “Yankee King of Spain”Doubleday, Doran and Company Inc. Garden City NY 1945 p.117

[8] DeRose, Chris. Star Spangled Scandal: Sex, Murder, and the Trial that Changed America. p.91

[8] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.117

[9] Swanberg, W.B., Sickles the Incredible pp.62-63

[10] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.116

[11] Hessler, James A. Sickles at Gettysburg Savas Beatie New York and El Dorado Hills CA, 2009, 2010 p.12

[12] Louisville Daily Courier, March 4th, 1859, Library of Congress

[13] Marvel, William, Lincoln’s Autocrat: The Life of Edwin Stanton University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 2015 p.103

[14] Hessler, James A., Sickles at Gettysburg pp.12-13

[15] DeRose, Chris. Star Spangled Scandal: Sex, Murder, and the Trial that Changed America. p.108

[16] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible p.63

[17] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel p.151

[17] Marvel, William, Lincoln’s Autocrat p.103

[18] Pinchon. Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.121

[19] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible p.64

[20] DeRose, Chris. Star Spangled Scandal: Sex, Murder, and the Trial that Changed America. p.114

[21] Marvel, William, Lincoln’s Autocrat p.104

[22] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.118

[23] The Washington Star, March 8th, 1859. In the Library of Congress, Chronicling America, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1859-03-08/ed-1/seq-1/#date1=1859&index=0&rows=20&searchType=advanced&language=&sequence=0&words=atrocious+butchery&proxdistance=5&date2=1859&ortext=&proxtext=&phrasetext=atrocious+butchery+&andtext=&dateFilterType=yearRange&page=1&loclr=blogser

[24] DeRose, Chris. Star Spangled Scandal: Sex, Murder, and the Trial that Changed America. p.154

[25] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles pp.118-119

[26] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel p.162

[27] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.120

[28] Marvel, William, Lincoln’s Autocrat p.105

[29] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel p.173

[30] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel p.173

[31] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.124

[32] DeFontaine, Felix. The Trial of the Hon. Daniel E. Sickles for Shooting Philip Barton Key, Esq., U.S. District Attorney for Washington, D.C., February 27th, 1859. p.22

[33] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel p.175

[34] Marvel, William, Lincoln’s Autocrat p.107

[35] Hessler, James, A., Sickles at Gettysburg p.15

[36] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.127

[37] DeFontaine, Felix. The Trial of the Hon. Daniel E. Sickles for Shooting Philip Barton Key, Esq., U.S. District Attorney for Washington, D.C., February 27th, 1859. p.25

[38] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.128

[39] DeFontaine, Felix. The Trial of the Hon. Daniel E. Sickles for Shooting Philip Barton Key, Esq., U.S. District Attorney for Washington, D.C., February 27th, 1859. pp.26, 30

[40] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.128

[41] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.129

[42] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.127

[43] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.128

[44] DaRose, Chris. Star Spangled Scandal: Sex, Murder, and the Trial that Changed America. p.278

[45] Pinchon, Edgcumb, Dan Sickles p.129

[46] DeFontaine, Felix. The Trial of the Hon. Daniel E. Sickles for Shooting Philip Barton Key, Esq., U.S. District Attorney for Washington, D.C., February 27th, 1859. p.90

[47] Marvel, William, Lincoln’s Autocrat p.110

[48] Pinchon, Edgcumb, p.129

[49] Marvel, William, Lincoln’s Autocrat p.110

[50] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible p.66

[51] Hessler, James, A., Sickles at Gettysburg p.17

So much to learn from. I’d never come across this story, for instance - and I thought I had a decent education in American History. Must say the threads of misogyny, marital violence and entitlement are sadly contemporary.

Fascinating read. Theater of the Absurd and lesson in inciting nonsensical public opinion. You’d think as a society we’d have progressed from this kind of manipulation but apparently we haven’t.