The Congressman Who Killed a Man Across from the White House and Got Away With It. Part Six: Politics and Promotion

This is the next installment of my work on America’s incredible scoundrel, General Dan Sickles. This part takes place between Sickles’s return to the Army of the Potomac in November, 1863, to just before the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. The next installment will deal with Chancellorsville and the Gettysburg Campaign up until June 28th, 1863. Enjoy.

Dan Sickles rise in the Army was due in part to his cultivation of political relationships, his ability to recruit and organize regiments of volunteers, and the good fortune be in an army where senior commanders were killed, wounded, or relieved regularly. He received his commission as a Colonel from the Governor of New York, and the Star of a Brigadier General through the efforts of Abraham Lincoln. His second star came with his appointment as commander of Third Corps in May, 1863.

To understand how Sickles rose from, Brigade, to Division, and Corps command, one needs to understand the tumultuous climate of the war in the East and the Army of the Potomac. The beginning of this section deals with the time following the relief of George McClellan after the Battle of Antietam in October 1863.

After successive failures George McClellan was relieved of command of the Army of the Potomac for his failure to destroy Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia at the Battle of Antietam. While McClellan’s Army had stopped Lee’s abortive invasion of Maryland, his failure to destroy Lee’s Army when he outnumbered it by more than two to one and had it backed up against the Potomac was the last straw for Lincoln, who fired him and appointed Major General Ambrose Burnside, commander of IX Corps to replace him.

McClellan’s relief divided the Army into pro and anti-McClellan camps. Despite his failures, McClellan had given birth to the Army of the Potomac. He has to be given credit for the Army’s organization and training which endeared him to many officers and soldiers. However, he constantly differed with Lincoln, Stanton, Scott, and Halleck regarding war aims, with McClellan constantly focused on a limited war against the Confederate Army, versus a clear strategy to defeat the Confederacy. McClellan was obstinate blaming others for his failures, including Scott who was America’s most successful and respected soldier, and after Scott’s retirement shifting blame to Lincoln, treating him disrespectfully in person and to others, describing Lincoln as the original gorilla. [1]

Likewise, McClellan was casualty adverse, in a speech to the Army told his soldiers that he would watch over them “as a parent over his children.... It shall be my care, as it ever has been, to gain success with the least possible loss...” [2] But there was no avoiding the fact that McClellan frequently exaggerated the strength of the Army of Northern Virginia’s as two to three times that of the Army of the Potomac, [3] and never pressed his own numerical advantage, even when in possession of hid enemy’s campaign plans as he did at Antietam. [4]

McClellan’s relief by Lincoln followed McClellan’s inability to defeat Lee at Antietam, his refusal to obey a direct order from Lincoln to pursue Lee into Virginia, and J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry division’s ride around the Federal Army and Washington, D.C. when he was relieved of command following the 1862 mid-term elections, many officers and soldiers grieved his loss, Colonel Charles Wainwright, the commander of First Corp’s artillery wrote of McClellan’s final review of the corps:

“Not a word was spoken, no noisy demonstrations of regret at losing him, but there was hardly a dry eye in the ranks. Very many wept like children, while others could be seen grazing at him in mute grief, one may almost say despair, as a mourner looks down into the grave of a dearly loved friend.” [5]

The sentiment was not shared by all, but it was a part of a continuing drama of leadership that plagued the Army until Ulysses S. Grant took command of all armies and made his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac. Colonel Regis De Trobriand wrote of McClellan, “The truth is that, with some grumbling, interested mostly, the army accepted the change as a man does a wife: "for better or for worse." [6]

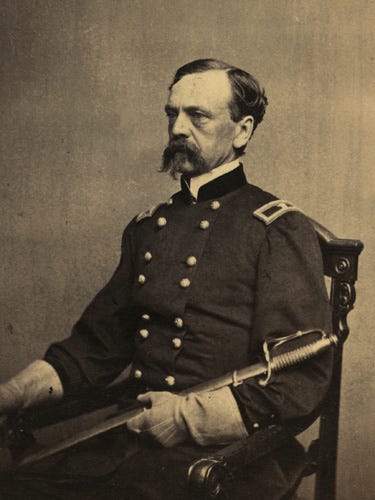

Major General Ambrose Burnside

But Ambrose Burnside, and honorable man who had not sought command of the Army of the Potomac was not the man for the job, and he considered himself unqualified for the command. [7] Burnside was well liked and imbued with humility seldom seen in the Army. [8] However, he set about his job with enthusiasm and reorganized the army’s seven army corps into three “grand divisions” and a reserve grand division. This brought about changes in command throughout the army as corps commanders were moved up to command the grand divisions, and others were named to command the vacant corps and division commands.

One of these changes affected Third Corps to which Sickles’s Brigade was assigned. “Fighting Joe” Hooker was elevated to command the the Center Grand Division which comprised the Third and Fifth Corps, with George Stoneman, the cavalry commander taking command of Third Corps. [9] Dan Sickles was promoted to command Hooker’s old division, despite his comparative lack of battlefield command experience as opposed to others. However, the two battles that he missed, Second Bull Run and Antietam did little for the reputation of the Regular Army officers in those fights. [10] His promotion was largely due to his cultivation of political friends, including Abraham Lincoln, who nominated him for promotion to Brigadier General the previous year and submitted it again until he was confirmed by the Senate. He was also buttressed by the support of influential newspapers. Sickles’s relationship with both Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln was friendly, being invited to one of Mary’s frequent séances where he hid and attempted to inject “a spirit of skepticism” into the medium’s presentation. Likewise, he presented his newly reinforced and reequipped division to Lincoln before Fredericksburg, with which Lincoln was impressed, telling Sickles, “Tell them I have never seen a better show.” [11]

Sickles’s Division joined the Army but was not committed to the battle, instead being held in a support role, which was a good thing for his soldiers. Burnside had the chance to catch Lee’s Army in a scattered condition by taking a direct route towards Richmond against the wishes of Lincoln and others. However, he was cautious and took so much time so that Lee was able to bring both James Longstreet and Stonewall Jackson’s large Corps into defensive positions above Fredericksburg. The battle was a bloody defeat for the Army of the Potomac. His plan was not bad, and as Bruce Catton wrote, Burnside “did his conscious best only to become the architect of unrelieved catastrophe.” [12] On December 13th Burnside insisted on sending division after division unsupported up Marye’s heights where Longstreet’s intrenched Corps waited. It was a slaughter. The Federal attacks were pressed hard and with great bravery, but repulsed by Longstreet’s men. Burnside wanted to renew the attack the following day, but was persuaded not to by his commanders. Longstreet was prepared to meet a new assault, and wrote of the battlefield carnage:

“Our musketry alone killed and wounded at least 5000; and these, with the slaughter by the artillery, left over 7,000 killed and wounded before the foot of Marye’s Hill. The dead were piled sometimes three deep, and when morning broke, the spectacle that we saw upon the battlefield was one of the most distressing I have ever witnessed. The charges had been desperate and bloody, but utterly hopeless. I thought, as I saw the Federals come again to their death, that they deserved success if courage and daring could entitle soldiers to victory.” [13]

In all, Burnside’s Army lost 12,653 men killed, wounded, missing or captured against a loss 5,309 for the Confederates. After the army recrossed the Rappahannock on the night of December 15-16, the regiments were greeted by bands playing requiems for the dead. Burnside rode passed one of the regiments, its members silently watched their commander pass by. “They had no words to offer him,” stated an officer, “nothing but pity.” [14]

Burnside attempted to restore the confidence of the army on January 20th and 21st by trying to cross the Rappahannock above Fredericksburg to surprise Lee, but the miserable weather created what became known as the Mud March, an act of folly, and other these conditions with a without confidence in itself or its commander, and Burnside became the butt of ridicule. Burnside was relieved when he paid a visit to the White House on January 25th where he met with Lincoln. Burnside “wanted to fire all his critical subordinates or he would resign himself.” [15] The subordinates included Hooker another Grand Division commander, William Franklin, as well as Major General William Farrar Smith. His demands staggered Lincoln who broke off the meeting to consult with Edwin Stanton and Henry Halleck. [16] Both were in favor or removing Burnside and after dealing with George McClelland’s incessant demands, Lincoln was not about to be pushed around by Burnside. However, Lincoln was set on appointing Hooker despite objections in the cabinet and the army. Halleck hated Hooker over a dispute dating to their time in California, but Halleck did not offer a suitable candidate. Lincoln removed Burnside and Joe Hooker appointed to command the army on January 25th 1863.

Hooker’s loose talk about the direction of the war where he said “both the Army and Government needed a dictator,” [17] was not unknown to Lincoln, but despite the qualms of Halleck and Stanton he elevated Hooker to command the Army of the Potomac. Burnside took his relief gracefully and did not resign. After a brief leave he went west and was given command of the Army of the Ohio. Lincoln also knew how to handle Hooker. He allowed Hooker to report directly to him, bypassing Henry Halleck the Commander of the Army, however his letter of appointment to Hooker was blunt in its honest and expectations.

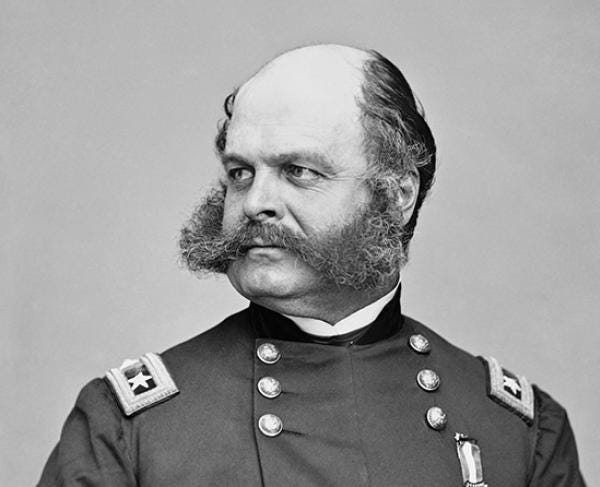

Major General Hooker

General:

I have placed you at the head of the Army of the Potomac. Of course I have done this upon what appear to me to be sufficient reasons. And yet I think it best for you to know that there are some things in regard to which, I am not quite satisfied with you. I believe you to be a brave and a skilful soldier, which, of course, I like. I also believe you do not mix politics with your profession, in which you are right. You have confidence in yourself, which is a valuable, if not an indispensable quality. You are ambitious, which, within reasonable bounds, does good rather than harm. But I think that during Gen. Burnside’s command of the Army, you have taken counsel of your ambition, and thwarted him as much as you could, in which you did a great wrong to the country, and to a most meritorious and honorable brother officer. I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship. The government will support you to the utmost of it’s ability, which is neither more nor less than it has done and will do for all commanders. I much fear that the spirit which you have aided to infuse into the Army, of criticising their Commander, and withholding confidence from him, will now turn upon you. I shall assist you as far as I can, to put it down. Neither you, nor Napoleon, if he were alive again, could get any good out of an army, while such a spirit prevails in it.

And now, beware of rashness. Beware of rashness, but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories.

Yours very truly

A. LINCOLN [18]

Hooker’s appointment to command did not surprise most officers, with whom he had few admirers, not for his gallantry but more for his political intrigues and personal morality. Likewise, “he was cursed with a very unstable temperament- one that today, probably, would be classified as “manic depressive.” [19]

However, his administrative acumen combined with his care for his soldiers quickly restored the morale and fighting spirit of the army. It also meant another series of promotions, one of them went to Dan Sickles, who took command of Third Corps, to the consternation of Oliver Howard who was senior to Sickles. Instead Howard received the largely German Eleventh Corps instead of Fritz Sigel who was Hooker’s first choice and a more natural fit. The Germans of the Corps were suspicious of Howard, known as “Old Prayer Book” by many in the Army for his Christian orthodoxy and zeal. Since many were freethinkers who were forced to flee their homeland due to the failure of the 1848 Revolution and the imposition of religious orthodoxy by the Catholic and Protestant monarchies of Germany and Austria, he was neither liked or trusted. [20]

The appointment of Sickles met with the deep reservations of George Meade, the commander of Fifth Corps, who believed that Sickles who he thought could be a bad influence on Hooker, and believed Sickles and Hooker’s Chief of Staff, Dan Butterfield, both politically connected Generals to be “political wire-pullers.” [21] Captain Charles Francis Adams Jr., the grandson of John Quincy Adams saw “Joe Hooker, Dan Sickles, and Dan Butterfield as a trio of depravity, “men of blemished character…” He wrote that the “Headquarters of the Army of the Potomac was a place where no self-respecting man would like to go, and no decent woman would go. It was a combination of bar-room and brothel.” [22]

Lincoln Reviews the Army of the Potomac with Major General Joe Hooker

Lincoln visited the Army at Falmouth in April with Mary and their son Tad, and spent a full day with Sickles and despondent over the losses of so many soldiers, cried out, “Sickles, can you see an end to this dreadful business? It breaks my heart to think how many of these brave fellows - here and across the River - will perish before peace can be restored!” Sickles too was sick over the losses and countered with Thomas Babington Macaulay’s famous lines from Herodotus: And how can man die better, Than facing fearful odds, For the ashes of his fathers, And the temples of the gods?” [23]

Princess Salm-Salm

Sickles was aware of Lincoln’s melancholy during the trip and following the review and a visit to Hooker’s headquarters escorted Lincoln to his headquarters tent where numerous officers wives lined up to greet the President. They all hoped to meet him, and Sickles somewhat mischievously suggested that they convey their admiration for him with a kiss. Since those were not the days when promiscuous kissing was acceptable, the ladies were bashful. This lasted until Agnes Leclerque of Baltimore, now Princess Salm-Salm the wife of the Prussian nobleman and soldier of fortune, Prince Felix de Salm-Salm. He had served in the Prussian and Austrian armies and was the Colonel of the 68th New York Infantry, and she volunteered to lead the charge. She “gave the President, not one, but several highly artistic kisses… Enviously the others sought to outdo the Princess. When it was all over, Lincoln was laughing like a little boy.” But Tad was watching and when his mother arrived the next day he told her of the episode, and it did not go well. “In Lincoln’s tent a high-pitched voice was heard deep into the night pouring psychopathic anathemas upon the unfaithfulness of men.” [24]

Mary Todd Lincoln in 1861

The next day Sickles learned that Mrs. Lincoln was infuriated with him and quite accurately blamed him for the kissing incident that he encouraged. Dan Butterfield noticed the “freezing coldness when Sickles was present,” and Mary reportedly told her husband, “As for General Sickles, he will hear what I think of him and his lady guests. It was well for him that I was not there.” [25] It was Lincoln, ever one for a good joke, pulled an artful one by naming Sickles to accompany him and Mrs. Lincoln on their return trip to Washington aboard a steamboat. Sickles recalled the voyage in his Oration at Fredericksburg following the war.

“I joined the President and his family on the the steamboat, at Acquia Creek,” Sickles recalled. “All went well until supper was announced. Seated at the table in a private cabin, face to face with Mrs. Lincoln, I at once I saw how much I was out of favor. I was not recognized. The President tried his best to put his wife in a better temper, but in vain; she evaded every overture, even the amusing anecdotes he related with characteristic tact and humor. Not a smile softened her stern features. At last Lincoln turned to me, exclaiming:

“‘Sickles, I never knew you were such a pious man until I came down this week to see the army.’

“‘I am quite sure, Mr. President,’ I replied, ‘I do not merit the reputation, if I have gained it.’

“‘Oh, yes,’ rejoined the President. ‘They tell me you are the greatest Psalmist in the army. The say you are more than a Psalmist - they say you are a Salm-Salmist.’

“‘This was more than Mrs. Lincoln could resist. She joined with a hearty laugh… and peace was restored.” [26]

Within weeks of the Lincoln’s visit, the Army of the Potomac would be on the offensive, its once dispirited soldiers now confident in themselves and their commander, Fighting Joe Hooker. He had used his superb administrative abilities to provide them fresh as well as victual vegetables, fresh meat, proper field sanitation, and medical care, as well as sundry items. Likewise, the army reorganization paid dividends in training and renewed confidence. As the Army of the Potomac prepared for the coming campaign its soldiers changed the words to a favorite ditty Marching Along, to

For Joe Hooker’s our leader, he takes his whisky strong. For God and our Country, we are marching along. [27]

To be continued…

Notes

[1] Goodwin, Doris Kearns, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, New York, NY. 2005, p.383

[2] Sears, Stephen W. To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1992 p.21

[3] McPherson, James, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 1998. p.361

[4] Wert, Jeffry D., The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, New York, NY. 2005, pp.148-151

[5] Wainwright, Charles, S., edited by Allan Nevins, A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journals of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, Da Capo Press, New York, NY. 1998 p.125

[6] De Trobriand, Regis, translated by George K. Dauchy, Four Years With the Army of the Potomac 1867, p.342

[7] Catton, Bruce, Never Call Retreat, Washington Square Press, published by Pocket Books, New York, NY. 1965 p.13

[8] McPherson, James, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. p.370

[9] Hebert, Walter H., Fighting Joe Hooker, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE. 1999 p.153

[10] Hessler, James A., Sickles at Gettysburg, Savas Beatie Publishing, El Dorado Hills, CA. 2009 p.33

[11] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, Anchor Books, New York, NY. 2002 pp.256-258

[12] Catton, Bruce, Never Call Retreat, Washington Square Press, p.13

[13] Longstreet, James, The Battle of Fredericksburg, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III based upon the The Century War Series of The Century of Magazine, Castle, Secaucus, NJ. pp.81-82

[14] Wert, Jeffry D., The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac, p.204

[15] Pinchon, Edgcum, Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and Yankee King of Spain, Doubleday, Doran, and Company, Garden City, NJ. 1945 p.169

[16] Marszalek, John F., Lincoln and the Military, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, IL. 2014 p.48

[17] Hebert, Walter H., Fighting Joe Hooker, p.165

[18] Marszalek, John F., Lincoln and the Military, p.48

[19] Lincoln, Abraham, Letter to General Joseph Hooker, January 26th, 1863. Retrieved from Lincoln’s Writings, https://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/letter-to-joseph-hooker-january-26-1863/

[20] Pinchon, Edgcum, Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and Yankee King of Spain, p.171

[21] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible, Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg, PA. 1956 and 1984, p.169

[22] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, p.221

[23] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, Mariner Books, New York, NY. 1996 p.65

[24] Pinchon, Edgcum, Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and Yankee King of Spain, pp.169-170

[25] Hessler, James A., Sickles at Gettysburg, p.47

[26] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible, pp.175-176

[27] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, [59]

What lovely details you reveal!

We have an image of a stern-face, depressed president and his crazy wife,

whom it married for money. How refreshing to hear these anecdotes!

The backroom brawls and all and squabbles flesh out what has been tired cliches,

I'm no Lincoln scholar, but your reports are more than of passing interest. I share

these with my husband who is a retired Assistant District Attorney and a history buff.

Your bibliography is extensive and admirable. Primary sources included.