The Congressman Who Killed a Man Across from the White House and Got Away With It. Part Five: War and Redemption

I continue the story of America’s incredible scoundrel, Congressman, and General Daniel Sickles. Tonight I move to the beginning of his service in the American Civil War. From the beginning of the war to his death in 1914, Sickles’s service in it often invokes a firestorm of opinion, much of it very negative concerning him. When I finish the series I will provide a postscript article to discuss the controversies surrounding him, during the war, and after during Reconstruction. I will not enter into that discussion yet, suffice to say that there are two sides to every tale and that many of Sickles’ esteemed critics often judge him by their standards, even reading into the decisions of others their own prejudices. So, on with the story.

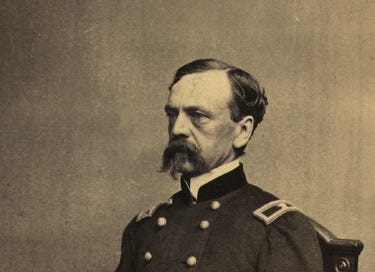

Brigadier General Daniel E. Sickles, 1862

Dan Sickles completed his term in Congress making few speeches and maintaining a relatively low profile, frequently entering and leaving through side entrances, but his personally enforced silence and humility could not last for long as the nation came apart. The secession crisis created confusion and Sickles’ estranged friend President James Buchanan, lacked the strength needed to resist the Secessionists. [1] As tensions rose and secession fever built, Sickles, the longstanding supporter of Southern states rights, who had declined to run for reelection “briefly transformed himself from outcast to firebrand.” [2] It was the kind of challenge that Sickles thrived upon, “whether it be political, financial, or sexual.” [3]

When secessionist troops opened fire on the transport Star of the West when the ship attempted to deliver supplies to Fort Sumter, Sickles was enraged. At one time he had been in favor of peaceful secession, but when the Confederates opened fire on the unarmed ship all former sympathy for them disappeared. Surprising his Southern colleagues he declared the attack on the ship as “naked, unmitigated war,” and declared:

It will never do, sir, for them [the South] to protest against coercion and, at the same moment, seize all the arms and arsenals and forts and navy-yards and ships… when sovereign states by their own deliberate acts, make war, they must not cry peace… When the flag of the Union is insulted, when the fortified place provided for the common defense are assaulted and seized, when the South abandons its Northern friends for English and French alliances, then the loyal and patriotic population of that imperial City [New York] are unanimous for the Union.” [4]

Sickles predicted that “the men of New York would go in untold thousands anywhere to protect the flag of its country and to maintain its legitimate authority.” [5] His speech was electrifying and hearkened back to his early career and what might have been. During the remaining days of his term he continued to speak out in the House against the actions of the South and sponsored legislation to bills to suspend postal service with the South and recover the funds in the United States Mint buildings which had been seized by seceding states. He thundered in the presence of his Southern friends who were still serving in the House, “Surely the chivalrous men of the South would scorn to receive the benefit of our postal laws,… “They cannot intend to remain, like Mahomid’s coffin, between heaven and earth, neither in nor out of the Union, getting all the benefits, and subjecting us to all its burdens.” [6]

The New York Times reported that Sickles was forceful, “clear” and “logical” in defense of his country, and his words were “attentively listened to by the members and crowded galleries,” to “decided effect.” [7]

Shortly thereafter, Dan Sickles left Washington to what many thought would be political and possibly personal oblivion, but they underestimated Sickles. His reunion with Teresa was brief as his ambition and desire for redemption, mixed with unbridled patriotism burned in his heart. Shortly after President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion, Sickles volunteered to help raise and lead the men of the Empire State into battle to restore the Union.

The idea began over a drink at Delmonico’s with Captain William Wiley, a friend from his Tammany Hall days who supported Dan during his trial. Wiley knew that Dan had been a Major in the New York State National Guard thought that Sickles would would be an ideal candidate to raise a regiment of volunteers. [8]

The future commander of the 55th New York, the French-born journalist and later Union General, Regis De Trobriand, wrote: “During the time of discussion he had been among those most conciliatory in regard to the pretensions and aggressions of the South. But when the sword was drawn he was one of those most ready to throw away the scabbard, saying that he considered himself by so much the more obliged to fight the rebellion as a soldier that he had been ready to make the greatest concessions as Congressman.” [9]

Taking up the challenge to raise a regiment, Sickles went to work, and “almost overnight, using flag-waving oratory, organizational skills, and promissory notes, he had his regiment, the 70th New York Volunteers well in hand.” [10] Sickles gave the recruiting speeches himself and with the 70th raised, Governor Edwin Morgan gave Sickles and Wiley the authority to recruit a brigade of five regiments. The brigade was rapidly filled with volunteers. Sickles’ good friend, Charles K. Graham, the head of the Brooklyn Naval Yard, for whom Dan had procured the job, left with 400 brawny naval yard workers who were eager to fight for the Union.” [11]

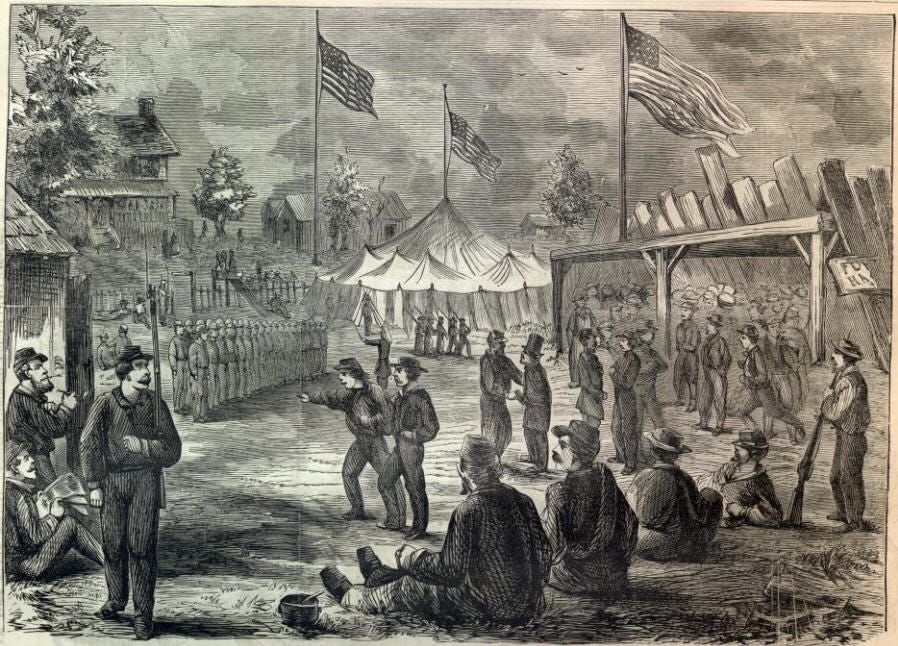

The Excelsior Brigade Camp in New York, 1861

Soon over 3,000 men were under his command, and Sickles was outfitting the new brigade, consisting of the 70th, 71st, 72nd, 73rd, and 74th New York Volunteers. Sickles promptly christened them the Excelsior Brigade, taking on the Empire State’s motto. However many of the brigade’s volunteers were scorned because of Sickles’ reputation, the brigade’s historian wrote, “no name was too bad for you; one would call you this and another would call you that, and even a person’s own relatives would censure him for joining such a Brigade as that of Daniel E. Sickles.” [12]

Even so, Sickles rapidly captured the hearts of his men. Volunteers were found throughout New York, as well as New Jersey, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, and the men represented the spectrum of White America; men of traditional Anglo-Saxon origin mingled with Irish, German, and Dutch immigrants. But he was so successful in recruiting that organizers of other regiments, especially in rural New York counties demanded that the Republican governor, Edward Morgan order Sickles to disband most of the brigade. Additionally, Morgan was pressured by other states because New York was exceeding its quota of volunteers. As such he ordered Sickles to send 2,000 of his recruits home. Sickles was furious as he had worked hard and sacrificed much to raise the brigade. [13] Believing the action politically motivated, by Morgan, a Republican, the Sickles pro-Union Democrat with few political allies, refused and went directly to Lincoln to get the brigade Federal recognition. At first Lincoln balked at the request, he needed troops but was yet unwilling to get in the way of what he saw as the individual state control of their militias. The result was a temporary impasse as Federal and New York officials argued about the brigade and the status of Sickles himself.

Sickles organizational and leadership skills were tested by the situation, and he went to extraordinary lengths to meet the needs of his soldiers for housing, food and sanitation. He “financed its camp for some time out of his own purse…. At one point he rented a circus tent from P.T. Barnum to house several hundred of his recruits. At another, with several companies or more quartered in a bare hall on lower Broadway, he contracted a cheap bath-house to give fourteen hundred men a shave and shower at ten cents apiece.” [14] To meet the need for cooked meals Sickles’ old friend Captain Wiley “commandeered cooks for the brigade from Delmonico’s, working in inadequate kitchens in side streets, they tried to turn out enough food for the men.” [15] The cost of the meals alone was over $12,000 a week. [16] Eventually the brigade was given a campsite on “Staten Island, near Fort Wadsworth, where he and his men could wait until the issue of mustering-in was settled.” [16]

Finally in July of 1861 the Excelsiors were officially mustered in to service as New York Volunteer troops and Sickles commissioned as a Colonel, functioning as the commander of the 70th New York and the de-facto commander of the brigade. Lincoln nominated Sickles for a commission as a Brigadier General of Volunteers but due to pressure from New York officials, still steaming at Sickles for going to Lincoln, the Senate delated confirmation for months, forcing Lincoln to re-nominate him a second time. He was finally confirmed by the Senate in May 1862, in some measure this was due to the influence of Sickles former defense attorney, Edwin Stanton who had succeeded the incompetent Simon Cameron as Secretary of War. However, the delay kept him from leading the brigade during the Peninsula Campaign and the Battle of Williamsburg where it first saw action. [17]

Sickles and his brigade first saw combat at Seven Pines during the Seven Day’s battle. Sickles acquitted himself well during the fighting, he seemed to be a natural leader of men, who cheered him as he led them into battle. He “made up for his lack of military training by acting on the battlefield with reckless courage, and was much admired for it by his men.” [18] The actions of the Excelsiors and their newly minted Brigadier were praised by the Army commander, George McClellan in a letter to Stanton, “The dashing charge of the Second and Fourth Regiments,…”the cool and steady advance of the Third, occurred under my immediate observation and could not have been surpassed.” [19] A news correspondent attached to the army wrote:

“Gen. Sickles had several narrow escapes; he was always to be found in the thickest of the fight. Had those gifted Senators who refused to confirm his nomination, but witnessed the enthusiasm of his troops when serving under him, and his military qualifications for office, they would do penance until re-elected.” [20]

Sickles’ Excelsior Brigade’s charge at Fair Oaks (Harper’s Weekly)

During the battle Sickles led his brigade in a bayonet charge against the Confederates. [21] During the fight, the 71st New York, the only regiment of the brigade not to have fought at Williamsburg panicked, reacting to an order to retreat. When Sickles discovered this he rode to the science and reformed the regiment, which General Joseph Hooker noted in his official report. [22] The success at Seven Pines was not followed up by McClellan, despite the urging of many officers, including Sickles. Richmond, which many believed could have been taken, remained in Confederate hands. Sickles performance during the Peninsular Campaign won Dan the respect and affection of his soldiers, as well as the respect of his division commander Fighting Joe Hooker. Unlike many other leaders who in their first taste of combat on the Peninsula saw the terrible carnage of battle, the immense numbers of casualties, and the suffering of the troops, Sickles maintained his composure, as others collapsed, “neither the casualties nor the state of the earth daunted Sickles.” [23] Hundreds of his Excelsiors, including his own aid-de-camp were killed or wounded during the campaign, and “the Excelsior Brigade, through steadily reduced by deaths, wounds and illness, had been forged into a body of hard-bitten, battle-wise soldiers educated in the necessities of war and in the tricks of self-preservation.” [24] A member of the brigade wrote, “It is no fable about the men of this Brigade thinking a great deal of the General.” [25]

Following the army’s withdrawal from the Peninsula and its return to encampments near Washington D.C., Sickles went back to New York to raise new troops to replace those killed or wounded during the campaign. He also took time to organize efforts to care of the children of the brigade’s soldiers, living and dead who were being taken care of at the Union Home School. He “gave a rally at the Seventh Regiment in New York City, where the General for an hour or more to the city’s volunteer firemen.” He traveled through the state successfully recruiting volunteers. Unlike Regular Army officers for whom spontaneous addresses to civilians were difficult, they came naturally to Sickles. He spoke what he believed, and the recruiting campaign delivered outstanding results. [26]

Due to this, he missed the battles of Second Bull Run and Antietam. His recruiting efforts were successful, even former political enemies were impressed by his service, and his ability to raise and organize troops. His reputation had been so completely rehabilitated by his war service that some of his “old backers in Tammany wanted him to run again for Congress.” [27] However, he was opposed by others, like his old friend Sam Butterworth, the man who held up Philip Barton Key long enough to catch up with Key and kill him. Butterworth had become a “Copperhead,” a member of an anti-war, faction that wanted to end the war and let the South go on its way; “to them, Dan had become a Lincoln man, a crypto-Republican.” [28] To the relief of his troops he declined the offer to run again. Chaplain Joseph Twitchell noted Sickles, “is getting fixed in his new place most successfully and will probably serve himself, as well as the country, better here than in a war of words.” [29]

During his recruiting efforts Sickles, now a military, as well as political realist, made many speeches, in which he recognized that conscription was inevitable. Having seen the brutal cost of war and the suffering of his men, Sickles complained of the lack of effort being provided in New York to the war effort. In a speech at the Produce Exchange, he praised the leadership and nerve of President Lincoln, and said, “A man may pass through New York, and unless he is told of it, he would not know that this country is a war…. In God’s name, let the state of New York have it to say hereafter that she furnished her quota for the army without conscription – without resorting to a draft!” [30]

When he returned to the army in November of 1862 his old division commander, Hooker had been promoted to corps command following the relief of George McClellan, and as the senior brigadier was promoted to command of the division. His, division, the Second Division of Third Corps was used in a support role at Fredericksburg and saw little action in that fight and only suffered about 100 casualties. His old friend and defense counsel Thomas Meagher, now commanding the Irish Brigade saw his brigade shattered in the carnage of at Fredericksburg. After Ambrose Burnside who had commanded the army during that fiasco was relieved of command Hooker was appointed by Lincoln as commander of the Army of the Potomac.

One of Hooker’s organizational changes was to establish a Cavalry Corps which was to be commanded by Major General George Stoneman, the commander of Third Corps. This left “Sickles as the corps’ ranking officer.” [31] Sickles was promoted to command the Third Corps by Hooker, who chose Sickles over another volunteer officer, David Birney. Had a professional officer rather than Birney been his competition, “Sickles would have remained division commander.” [32] Sickles was given the corps “on a provisional basis, for his appointment as a major general had not yet been confirmed by the Senate and corps command was definitely a two-star job.” [33] Once again it was political enemies in the Senate, this time Republicans who did not trust the Democrat, who delayed Sickles’ promotion to Major General, but he was finally confirmed on March 9th, 1863, with his promotion backdated to November 29th, 1862. “Professionals in the army attributed his rise to his “skill as a political maneuverer.” Few men, however, questioned his personal bravery.” [34]

Notes

[1] Knoop, Jeanne W., “I Follow the Course, Come What May” Major General Daniel Sickles, USA: A Biographical Interpretation From A Woman’s Point of View, Vantage Press, New York, NY. 1998 p.65

[2] Hessler, James A. Sickles at Gettysburg Savas Beatie New York and El Dorado Hills CA, 2009, 2010 p.21

[3] Knoop, Jeanne W., “I Follow the Course, Come What May” Major General Daniel Sickles, USA: A Biographical Interpretation From A Woman’s Point of View, p.65

[4] Hessler, James A. Sickles at Gettysburg p.111

[5] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles Anchor Books, a Division of Random House, New York 2003. p. 212

[6] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles p.214

[7] DeRose, Chris. Star Spangled Scandal: Sex, Murder, and the Trial that Changed America. Regnery History, Washington, D.C. p.301

[8] Knoop, Jeanne W., “I Follow the Course, Come What May” Major General Daniel Sickles, USA: A Biographical Interpretation From A Woman’s Point of View, p.69

[9] De Trobriand, Regis, translated by George K. Dauchy, Four Years With the Army of the Potomac 1867 p.417

[10] Sears, Stephen W. Controversies and Commanders Mariner Books, Houghton-Mifflin Company, Boston and New York 1999 p.201

[11] Knoop, Jeanne W., “I Follow the Course, Come What May” Major General Daniel Sickles, USA: A Biographical Interpretation From A Woman’s Point of View, pp.69-70

[12] Hessler, James A., Sickles at Gettysburg p.23

[13] Knoop, Jeanne W., “I Follow the Course, Come What May” Major General Daniel Sickles, USA: A Biographical Interpretation From A Woman’s Point of View, p.70

[14] Catton, Bruce, The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road, Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p. 153

[15] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles p.222

[16] Knoop, Jeanne W., “I Follow the Course, Come What May” Major General Daniel Sickles, USA: A Biographical Interpretation From A Woman’s Point of View p.72

[17] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles p.222

[18] Robertson, William G., The Peach Orchard Revisited: Daniel E. Sickles and the Third Corps on July 2, 1863 in The Second Day at Gettysburg, Edited by Gary Gallagher, The Kent State University Press, Kent, OH. 1993 p.38

[19] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville Mariner Books, New York, NY. 1996 p.65

[20] Hessler, James A., Sickles at Gettysburg pp.30-31

[21] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible p.149

[22] Knoop, Jeanne W., “I Follow the Course, Come What May” Major General Daniel Sickles, USA: A Biographical Interpretation From A Woman’s Point of View, p.79

[23] Reports of Brig. Gen. Joseph Hooker, U.S. Army, commanding Second Division, of the engagement at Oak Grove, or King’s School-House, and the battles of Glendale, or Nelson’s Farm (Fraizer’s Farm), with resulting correspondence, and Malvern Hill. July 14th, 1862. In War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I - Volume XI - in Three Parts. Part II. - Reports, Etc. Government Printing House, Washington, DC, 1884. p.109

[24] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles p.245

[25] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible copyright by the author 1958 and 1984 Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg PA. p.153

[26] Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac Simon and Schuster, New York and London 2005 p.222

[27] Knoop, Jeanne W., “I Follow the Course, Come What May” Major General Daniel Sickles, USA: A Biographical Interpretation From A Woman’s Point of View, p.84

[28] Hessler, James A., Sickles at Gettysburg p.32

[29] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles p.245

[30] Hessler, James A., Sickles at Gettysburg p.32

[31] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles p.252

[32] Wert, Jeffry D., The Sword of Lincoln p.223

[33] Sears, Stephen W. Controversies and Commanders p.206

[34] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible p.168

[35] Wert, Jeffry D. The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac p.223

What a complex man - and in a time of such upheaval. His passion to represent his state in battle for the life of the country gives a deeper picture of the man who killed but was exonerated for murdering his rival.