The Congressman Who Killed a Man Across from the White House and Got Away With It. Part Seven: Courage at Chancellorsville

This is the seventh installment of my work on America’s incredible scoundrel, Congressman and General Dan Sickles. This section deals with the Battle of Chancellorsville where Sickles and Third Corps performed well. Because this was all new work, I had to cut it off there and save the period between Chancellorsville and Hooker’s relief just prior to Gettysburg until the next installment. I hope that you enjoy.

Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker

Having been delayed by incessant rain and flooding since the beginning of April, Joe Hooker ordered the Army of the Potomac into action with the intent of crushing Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia on April 27th with the advance to begin on the 28th. [1] While led the Army of the Potomac on its march to defeat the Army of Northern Virginia, Dan Sickles was at the head of the Third Corps. He commanded about 19,000 of the best soldiers in the Army. His divisions included Hooker and Kearny’s veterans and such illustrious units as the Irish Brigade. [2]

Robert E. Lee was not expecting Hooker’s offensive to hit where it did, and had sent James Longstreet’s First Corps to Suffolk, to prevent a possible attack from Union Forces, in Hampton Roads, including Ambrose Burnside’s former Ninth Corps which had been with the Army of the Potomac at Antietam and Fredericksburg. This left Lee with Stonewall Jackson’s massive Second Corps comprise of the six excellent divisions commanded by Jubal Early, Robert Rodes, A.P. Hill, Raleigh Colston, and two divisions of Longstreet’s, those of Lafayette McLaws and Richard Anderson, as well the bulk of J.E.B Stuart’s Corps. [3] However, most were located southeast of Fredericksburg, as Lee expected the focal point of the upcoming Federal offensive to take place downstream of Fredericksburg.

Longstreet had left lines of strong entrenchments which the remaining Confederate units occupied. Hooker had no intention of following Burnside’s attack on Fredericksburg the previous November. However, Hooker’s initial movements seemed to confirm as units of John Sedgwick’s Sixth and Reynold’s First Corps created diversions on that front. [4] Sickles and Third Corps were part of that but sent west to reinforce the main thrust of the Second, Fifth, Eleventh, and Twelfth Corps crossing the Rappahannock north and west of Fredericksburg, and advancing through the swampy woodlands known as the Wildness in the direction of a crossroads called Chancellorsville. To the west of that a third prong of the offensive comprising the majority of the Cavalry Corps was sent towards Richmond on a raid to disrupt Lee’s communications with the Confederate Capitol. The intent was to surround and destroy Lee by fixing his forces at Fredericksburg and trapping them between the main force and the Corps of Sedgwick and Reynolds. If successful it would crush Lee in a pincers movement, [5] the likes of which had not been seen since Napoleon.

Hooker was well aware of the locations of Lee’s forces thanks to the efforts of Colonel George Sharpe’s Bureau of Military Information. The B.M.I. was created by Hooker with the intent of creating an efficient and effective source of military intelligence to replace the wildly inaccurate and inflated reports supplied to George McClellan by Allan Pinkerton’s private detectives. [6] Sharpe sent spies trained to observe and identify military formations including their numbers and number of artillery pieces. His men interrogated Confederate prisoners and provided Hooker with information with estimates counted brigade by brigade. The B.M.I.’s “count of Lee’s infantry came to 54,600, just 1,600 short of its actual numbers. In estimating Lee’s artillery at 243 guns, the B.M.I. over counted by just 23.” [7]

Hooker devised a very good plan to defeat Lee, and had it worked the Confederacy might have collapsed in 1863. His army numbered close to 135,000 men, and outnumbered Lee by over 2 to 1, although numerous 2-year and 9-month regiments were scheduled to demobilize between April and June. This did not prevent his offensive though a few hundred soldiers of the 24th New York refused to go with the regiment which decided to serve another campaign before going home, and were placed under the charge of the Army’s Provost Marshal. However, Hooker was confident, maybe overly so, reportedly remarking, “May God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none.” [8]

The Army of the Potomac moving towards Chancellorsville

Hooker’s initial deployments were very successful, causing Lee some consternation as Sedgwick and Reynold demonstrated on the Federal left, the main force crossed the Rappahannock at fords and by a pontoon bridge emplaced by the Engineer Brigade. The crossings were executed quickly and effectively. Hooker wrote,

“By making a powerful demonstration in front of and below the town of Fredericksburg with part of my army, I was able, unobserved, to withdraw the remainder, and, marching nearly thirty miles up the stream, to cross the Rappahannock and the Rapidian unopposed, and in four days’ time to arrive at Chancellorsville, within five miles of the coveted ground, all this without General Lee having discovered that I had left my position in his front.”[9]

His major mistake in the initial part of the battle was sending most of George Stoneman’s 12,000 man Cavalry Corps so far west and south of his infantry where they could not provide a screen for them to alert them of Confederate movements, nor be in position to attack the Confederate infantry in the open and on the march. Confederate artillery commander Porter Alexander considered it Hooker’s fatal mistake, as “This proved insufficient to keep him informed of the Confederate movements, even though their efforts were supplemented by many signal officers with lookouts and field telegraphs, and by two balloons.” [10]

Nonetheless, Hooker had stolen a march on Robert E. Lee and put the Confederate Army in danger. But once Lee recognized the danger and acted with great speed to block Hooker’s forces from hitting Fredericksburg from the west, with Anderson’s division, maintaining a watch on the Union forces across from Fredericksburg with Early’s division and preparing Jackson to attack Hooker. However, once his forces were across the Rappahannock and Rapidian, Hooker inexplicably stopped his advance before breaking out into the open country south of the Wilderness, despite finding out that Lee was on the move. Prior to Hooker halting the advance, George Meade was uncharacteristically elated, sensing a victory, telling George Slocum of Twelfth Corps, “This is splendid, Slocum, hurray for Old Joe! We are on Lee’s flank and he doesn’t know it.” [11]

Though most of the cavalry was out of touch with the army, Alfred Pleasanton’s remained with a few squadrons of cavalry and horse artillery batteries. On the 30th of April, Pleasanton’s scouts captured a Confederate messenger with Lee’s orders to McLaws about his plan. It was a gift. Pleasanton promptly took the information to Hooker, noting that since Lee intended to give battle at Chancellorsville, that he “anticipate him by moving on to Fredericksburg.” Pleasanton accurately noted that a march of three or four miles would place them on open ground where the army could deploy on line and make use of their superiority in artillery. [12]

Instead of moving boldly as he had to outflank Lee and get his army across the rivers, Hooker refused to move his soldiers to the recommended line from Chancellorsville to Spotsylvania Courthouse that afternoon. [13] It was to prove costly. Instead of having four infantry corps prepared to receive and attack Lee made, he began his movement out of the Wilderness the next morning with with the Second and Twelfth Corps leading supported closely by the Fifth, Eleventh, and Sickles’s Third Corps. They had barely begun their movement when they ran into the advance elements of Jackson’s Corps and were making progress against them. Then, Hooker lost his never and ordered them back to defensive positions. It was an order that drove another nail into hopes foe victory. Slocum began to retreat while Darius Couch of Second Corps considered outright disobedience, sending the Chief Engineer of the Army, Gouverneur Warren to tell Hooker of the advantages of fighting, but it was too late, Couch had begun to obey the order when Hooker’s belated reply to fight, disgusted he replied, “Tell General Hooker he is too late… The enemy are already on my right and rear. I am in full retreat. [14] Alfred Pleasanton wrote, “From that time the whole situation was changed. Without striking a blow, the army was placed on the defensive. The golden moment had been lost, and it never appeared again to the same extend afterward…” [15] Gouverneur Warren recommended an attack along the River road to turn the Confederate flank along the Rappahannock, but Hooker rejected the suggestion, electing to strengthen his defensive position to await an attack by Lee. [16] Warren wrote:

“I thought, with our position and numbers, to beat The enemy’s right wing. This could be done by advancing in force on the other two main roads toward Fredericksburg, each being in good supporting distance, at the same time throwing a heavy force on the enemy's right flank by the river road. If this attack found the enemy in extended line across s our front, or in motion toward our right, it would have secured the defeat of his right wing, and consequently the retreat of the whole.” [17]

Hooker’s indecision was brought about by several factors, mostly that he never had been the Army commander and as a division and corps commander had always had someone above him, his uncertainty of the location of Longstreet’s divisions, but the biggest, as he later told Abner Doubleday, “for once I lost confidence in Hooker.” [18] Sickles’s biographer, Edgcumb Pinchon noted that his collapse was “a typical manic depressive reaction.” [19] While Hooker doubted Hooker, Robert E. Lee had a two man counsel of war with Stonewall Jackson. Despite the strength of the Federal position, Jackson with his characteristic distain of the abilities of Union soldiers wanted to make a frontal attack, despite his units taking significant casualties against the divisions of George Sykes. However, Lee made the bold decision to again divide his forces. Early would remain at Fredericksburg, while McLaws faced east to oppose any advance by Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps. Anderson’s division manned works along the Plank Road with Lee remaining with them. Lee then ordered Jackson at the head of Rodes, A.P. Hill’s and Colston’s divisions to embark on a 14 mile march to the south of the Federal lines to strike Oliver Howard’s Eleventh Corps.

Hooker had a strong defensive front on the east facing Lee, but the majority of his army was in the thick tangle of woods in the Wilderness where they were practically blind without Stoneman’s cavalry and without the ability to employ his strong artillery. This line formed a rough semicircle from the Rappahannock on his right where Meade’s Fifth Corps was in a strong position, on his right was Couch, the Slocum, Sickles, and Howard, whose Eleventh Corps, right flank was exposed. It is possible that Hooker, due to his uncertainty of the Corps placed it there to keep it far from the action, but his decision placed it in the directly in line of Stonewall Jackson’s planned attack. [20]

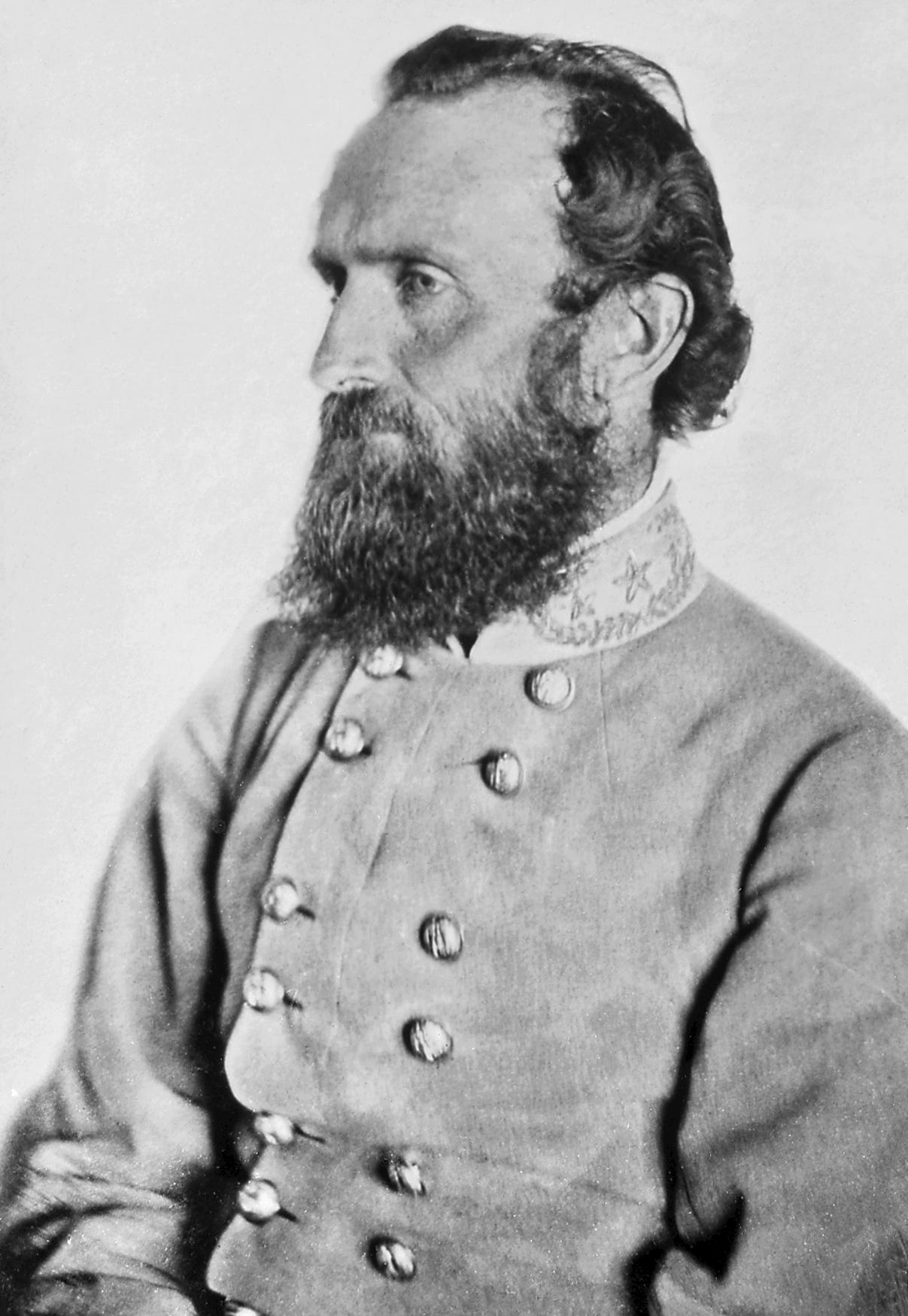

Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson

Jackson’s column was only a couple miles into its movement when Federal lookouts from Birney’s division of Sickles’s Third Corps at Hazel Grove spotted them and reported it to Sickles who relayed it to Hooker. The lookouts reported that the Confederates had turned south at a crossroads near Catherine’s Furnace. [21] Hooker then sent orders to Howard and Slocum to be prepared for a possible attack and to push their pickets forward. [22] Hooker even recommended that Howard pull back to a better defensive line near Dowdall’s Tavern which Howard refused,

Sickles then asked permission to attack which Hooker gave. Sickles sent Amiel Whipple’s forward with 1st and 2nd U.S. Sharpshooter Regiments formed by Hiram Berdan, who commanded the 1st U.S. Sharpshooters. The Sharpshooters acted a a thick screen of pickets for the infantry divisions and quickly fell on Jackson’s rear guard. [23] The Confederates were from the 23rd Georgia which had been detached to form the rear guard, and the Sharpshooters captured 300 of them. [24] A provost officer led them to Hazel Grove and Sickles’s asked who had captured them, when the office said he did, Sickles scoffed. “The devil you did…, there’s the Sharpshooters- they captured those men.” [25] A captured Confederate Lieutenant told him that Jackson was going to attack the army’s right flank, but Sickles, assuming that he was lying was convinced that Lee was retreating because his soldiers had seen Confederate wagons going south at the road junction. Hooker too, having consulted maps of the area believed that Lee was withdrawing and began planning to attack. Hooker wired Butterfield, “We know that the enemy is fleeing and trying to save his trains… Two of Sickles’ divisions are among them.” [26]

Despite being warned by Hooker to guard against an attack, Oliver Howard had done little to prepare, he told Hooker that he would strengthen his line and that his men would be demoralized by a withdrawal. To make his point he sent one of Sickles’s brigades and an artillery battery offered as reinforcements back, in order to convince Hooker that he needed no help. [27] All Howard did was to face two guns with just two regiments numbering barely 900 soldiers to his west thinking that there was little chance of an attack from that direction, additionally a brigade he detached earlier in the day had not returned leaving a half mile gap on his left between him and Slocum. [28] However, Jackson’s men were perilously close and preparing to launch their attack even as Sickles was in action against the Confederate rear guard. Alfred Pleasanton arrived to consult with him and see the situation for himself. Sickles asked for cavalry and Pleasanton gave him the 6th New York and deployed the 8th and 17th Pennsylvania and Martin’s New York Battery on the west edge of the Hazel Grove clearing. [29]

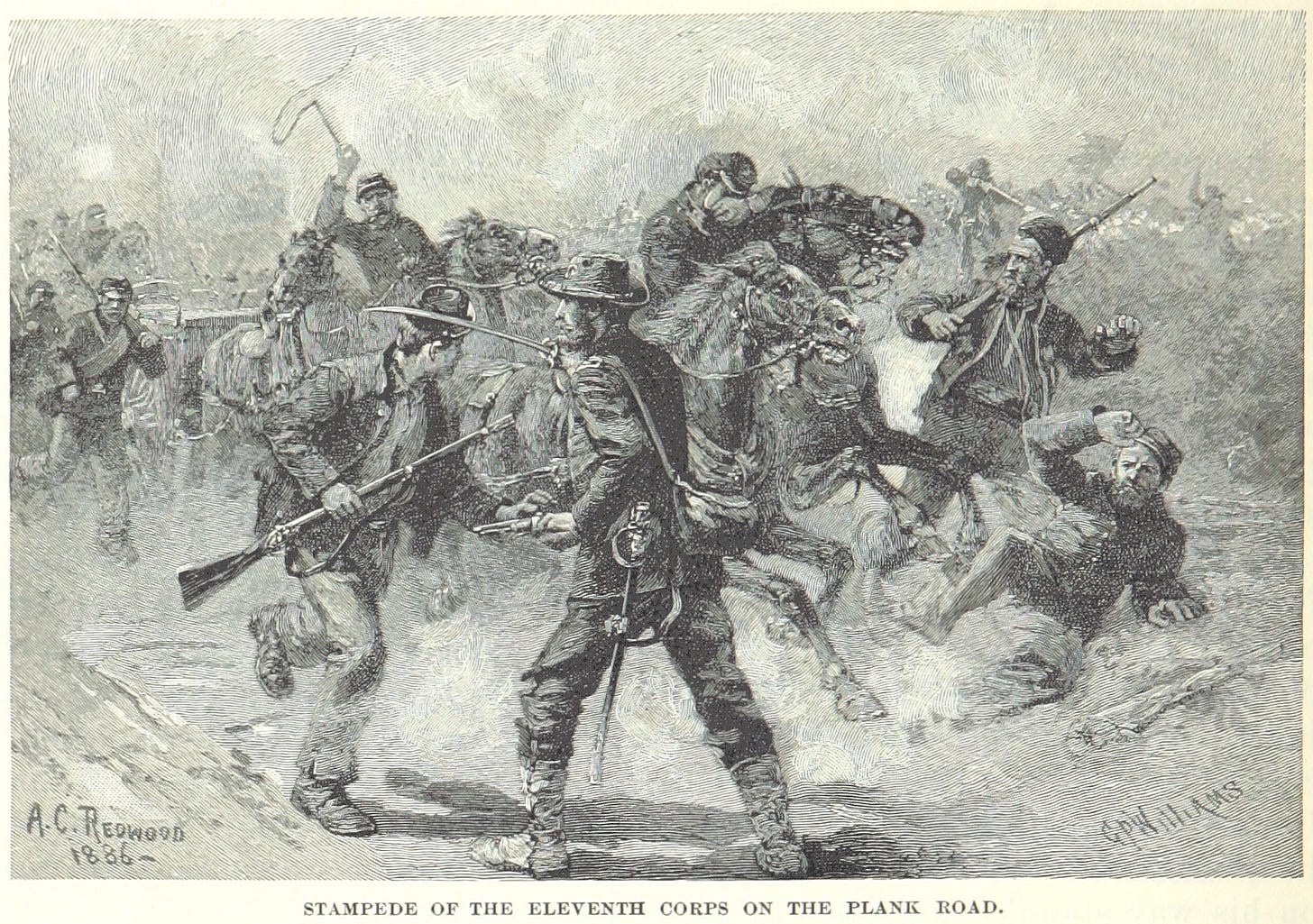

To the west, Stonewall Jackson was personally directing the deployment of his divisions for their attack. His troops had maintained absolute quiet during their movement to the attack, no bugle calls, no singing, or cheering. They silently gathered in the woods just a few hundred yards west of Howard’s troops. When they were set Jackson turned to General Rodes, the only non-West Point graduate in the Army of Northern Virginia, and said, “Are you ready, General Rodes?” Rodes, impatient to advance replied, “Yes, sir!” Jackson then gave the order, “You can go forward then.” [30] With that order the Confederate storm broke on Howard’s unsuspecting troops who were either at their evening meal or relaxing, behind well built breastworks that unfortunately for them faced south.

Howard wrote:

“With as little noise as possible, a little after 5 P.M., the steady advance of the enemy began. It’s first lively effects like a cloud of dust driven by a coming shower, appeared in the startled rabbits, squirrels, quail, and other game flying wildly hither and thither in evident terror, and escaping, where possible, into adjacent clearings.” [31]

The Confederate advance swept through Charles Devens division. Devens, like Howard was the wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time. Devens took command of the division a week before the campaign and neither respected or was respected by his German troops. Likewise, having injured his leg the day before, he was resting at his headquarters drinking brandy to ease his pain which “improved neither his temperament nor his judgment” as the attack began. [32]

The volleys of musket fire from the Rodes’ division swept into the Union camps and ranks. The regiments on the far right melted away as the panic stricken troops ran like frightened sheep even as officers attempted to rally them and others sought to form regiments further to the rear. Stonewall Jackson rode forward with his advanced units urging them to “press them!” However, the great German American leader, Carl Schurz command the next division in line had quietly in disobedience to Howard faced three regiments westward earlier in the day to attempt to protect the flank. [33] Howard tried to stem the panic of Devens’ division, but couldn’t, as they were running for their lives, the remnants of Eleventh Corps delayed Rodes just 15-30 minutes before breaking under the Confederate onslaught, but they bought some time for Hooker to try to recover before the Confederates could sweep the Federal position. [34]

John Collins of the 8th Pennsylvania recounted, “General Howard, who seemed the only man in his own command that was not running at that moment. He was in the middle of the road, his maimed arm embracing a stand of colors some regiment had deserted, while with his good arm he was gesticulating to the men to make a stand by their flag… Pharaoh and his chariots could have held back the walls of the Red Sea as easily as these officers could resist retreat.” [35]

The fleeing men of Eleventh Corps poured into Slocum’s Twelfth Corps, throwing that unit into confusion.

Hooker ordered Sickles’s reserve division under the command of Hiram Berry, a division of Couch’s Second Corps and several batteries face west and go into the fight to stem the tide near the high ground at Fairview.

Upon discovering the Eleventh Corps troops fleeing to his rear, Sickles and Pleasanton entered the fray. The attack on the Confederate rear guard had placed Sickles and his two divisions in a potentially vulnerable spot, away from the main Federal line with the enemy advancing on his rear. Pleasanton ordered Major Huey commander of the 8th Pennsylvania to attack, and [36] at the same Sickles exchanged words with Major Peter Kenan, Commander of the first squadron, a man he much prized to attack the swarming Confederates. “I’m sorry to do this Kenan, but it’s our only chance.” With a quick smile Kenan saluted. “I will do it!” [37] Major Huey shrilled the order to advance. Four hundred Union Cavalry troopers advanced at a trot before bursting into a gallop, sabers flashing into the oncoming host of twenty-thousand surging Confederates.

“They crashed with with slashing sabers into the head of the column. Falling like leaves, horse and man, before a blast of bullets, the first squadron yet managed to throw the enemy into an instant of confusion. The second and third squadrons, immediately behind, met momentarily empty guns and rode a thinning charge over ground cluttered with floundering horses, shattered men… For a moment the Rebels, scattering right and left, had thought that the whole Union cavalry was coming down on them. And, before they had recovered from their panic, Pleasanton had his guns in position and was raking their front with shrapnel aimed to ricochet into their ranks at a three-foot level. Nothing could stand against that murderous, searching fire. And the Rebels, halted their berserk pursuit, wilted back into the shelter of the Forrest.” [38]

Pleasanton then sent three squadrons of the 17th Pennsylvania to run down the retreating stragglers of Eleventh Corps in order to clear the way for his artillery to open fire on the advancing Confederates which helped slow down the rebels. [39] Sickles turned Birney’s and Whipple’s divisions back to oppose the Confederate assault, occupying Hazel Grove in force. An early historian of the Army of the Potomac wrote, “if Sickles' command had not arrived in time to have stuck Jackson’s right and rear, there is no telling where the disaster to Hooker’s army would have ended that night.” [40]

That night Sickles, having secured Hooker’s permission for another attack sent Birney’s division into Jackson’s legions. General Alpheus Williams, no friend or admirer of Sickles wrote:

“A tremendous roll of infantry fire, mingled with yelling and shoutings almost diabolical and infernal, opened the conflict on the side of Sickles’s division. For some time my infantry-and artillery kept silent, and in the intervals of the musketry could distinctly hear the oaths and imprecations of the rebel officers, evidently having hard work to keep their men from stampeding. In the meantime Sickles artillery, firing over the heads of the infantry, and the din of arms inhuman yelling and cursing redoubled. All at once, Berry’s division, across the road on our right, opened in heavy volleys, and Knipe (commanding my right brigade next to the Plank Road on the South) followed suit. Best (chief of artillery of the Twelfth Corps) began to thunder with his thirty-odd pieces. In frontman and on the flanks, shell, and shot, and bullets were poured into these woods, which were evidently crowed with Rebel masses preparing for the morning attack. Along our front and Sickles' flank probably 15,000 or more muskets we belching an almost incessant stream of flame, while from the elevation just in the rear of each line from forty to fifty pieces of artillery kept up an uninterrupted roar reechoed fromthewoodswitharedoubled echo, from the bursting shells which seemed to fill every part of them with fire and fury. Human language can give no idea of such a scene - such an infernal and yet sublime combination of sound, and flame, and smoke, and dreadful yells of pain, of triumph,or of defiance. Suddenly, almost on an instant, the tumult is hushed; hardly a voice can be heard. One would almost suppose that the combatants were holding breath to listen for one another’s movements. But the contest was not renewed… [41]

Intermittent clashes continued into the night but Robert Rodes seeing the confusion in his ranks elected to stop the advance as darkness fell on the battlefield, noting, “Such was the confusion and darkness that it was not deemed advisable to make a further advance.” [42] Even so his order did not reach some of the men in the leading brigades who continued to advance. Federal and Confederate soldiers continued to exchange fire, occasionally shooting at their comrades in the darkness, as apparitions seemed to come and go. Stonewall Jackson ended up becoming of what we colloquially call “friendly fire.” The General was already seeking a way to exploit his success that night instead of realigning and resting his troops for an attack in the morning. [43] Together with A.P. Hill and his staff decided to conduct a reconnaissance, against the recommendation of one staff office who told him In the darkness the clatter of their horse’s hooves surprised the men of the 18th North Carolina of James Lane’s brigade [44] who thought that they were from Pleasanton’s cavalry, probably the 8th Pennsylvania who earlier had created so much confusion in the Confederate ranks. Jackson was mortally wounded, A.P. Hill wounded and two staff members killed in the volley. When Lee heard the news he exclaimed, “Any victory is dearly bought which deprives me of the services of General Jackson.” [45] Lee gave J.E.B. Stuart command of Second Corps and ordered him to press the Federal position to secure victory in the morning.

George Meade reacted to the collapse of Eleventh Corps by creating a defensive line by sending Sykes division of Regulars to prevent the Confederates from reaching Ely’s Ford and and placing the rest of his Corps to halt the fleeing Eleventh Corps soldiers and to stop the Confederates, bringing up artillery. One of Meade’s aides noted “in an incredibly short amount of time…. About sixty guns were collected with the Fifth Corps line as they [the enemy] would have received a warm reception.” [46] Couch and Slocum also made preparations for the the Confederates.

Sickles now had two divisions on the high ground at Hazel grove as well as significant artillery. Sickles realized the importance of the high ground that dominated the battlefield and did not want to give it up without a fight. Stuart, now commanding Jackson’s Corps also realized that it was the key to the battlefield and attacked. His attacks were turned back with heavy losses, but Hooker ordered Sickles to withdraw from the position. Regis de Trobriand wrote, “General Hooker virtually lost the battle of Chancellorsville by an error as unexpected as inexplicable.” [47]

Sickles left Pleasanton in command and rode to confront Hooker at his headquarters at the Chancellor house. He had just arrived when a shell struck a column he was leaning against, knocking him senseless, he rose and “peevishly reiterated his original order. He would send him no more ammunition “since it would only fall into enemy hands.” Sickles later recalled it as “the bitterest experience of his military career.” [48] Porter Alexander wrote, “There has rarely been a more gratuitous gift of a battle-field. Sickles had a good position and force enough to hold it, even without reinforcements, though ample reinforcements were available.” [49] Most experts believed that Sickles could have held the position, albeit with considerable loss, but Hooker was no longer thinking about defeated Lee, but saving the Army of the Potomac, [50] likewise refusing George Meade’s plea to launch an attack on the weak Confederate right wing, which if turned would unhinge Lee’s line and force him to stop attack Hooker with Anderson and McLaws’s divisions, thereafter removed himself having lost the ability to think clearly, without appointing a replacement to command the army, leaving it for a time without a head. These decisions only aided Lee.

Federal Troops Holding the Line on May 3rd

Sickles obeyed the order under heavy pressure as his rearguard punished the advancing Confederates, but it took time before Hooker was cogent enough to place Darius Couch in command. Shortly after Sickles completed his withdraw, Stuart moved to occupy the heights and “he at once ordered 30 pieces of artillery to that point to concentrate their fire on Fairview.” [51] De Trobriand wrote, “the enemy, finding the ground free, which we had just quitted, promptly took possession of it, and placed his artillery there, giving him a converging fire, without hindrance, upon the centre of our position.” [52] Those guns under the command of Porter Alexander opened fire at the Federal lines including Fairview not far from the Chancellor house where Federal artillery behind their infantry unleashed a murderous fire on the Confederate lines. [53] The artillery started a fire in the underbrush north of the Plank Road, where many wounded remained from the earlier fights.

Union Artillery at Fairview engaging Confederate Artillery at Hazel Grove

The Confederate attacks and Federal counterattacks were bloody affairs. Two division commanders of Sickles Third Corps, Generals Berry and Whipple, as well as Brigadier General Gresham Mott. Confederate Brigadier General Frank Paxton of Rodes Division was also struck down. Third Corps was holding its own despite a shortage of ammunition, under great disadvantages [54] but when Berry was struck down, Brigadier General Joseph Revere, in command of Sickles’s old Excelsior brigade, mistakenly assumed that he was in command of the division, inexplicably withdrew them and another three regiments out of the battle while Sickles was on another part of the line directing his troops. [55] Sickles was infuriated and instantly relieved Revere of command, but the unauthorized retreat enabled the Confederates an open path to Fairview. Mott’s brigade now under the command of Colonel W. J. Sewell made an epic stand that cost the Confederates dearly. “The enemy made desperate efforts at that point to break the Union line, and hurled regiment after regiment on young Sewell, only to sacrifice their colors. The 5th New Jersey took three stands of colors, and the 7th took five; while the brigade took 1,000 prisoners.” [56] De Trobriand noted how Sickles maintained his calm through the day in the forward lines with his soldiers, “Sickles goes by in his turn at a walk, with a smiling air, smoking a cigar. 'Everything is going well,' said he, in a loud voice, intended to be heard.” [57] His calmness under fire helped inspire his soldiers, earning their undying loyalty.

Colonel Sewell’s Soldiers Escort Confederate Prisoners and their Regimental Colors on May 3rd 1863

The fight on May 3rd was intense and, “Casualties exceeded 17,500 on both sides in the five hours of combat; Southerners’ losses amounted to nearly 9,000.” [58] Upon regaining his senses Hooker ordered the army to retreat to another defensive line, ending the combat of May 3rd.

May 4th was uneventful with the exception of exchanges of artillery and sharpshooter fire as Lee decided that an attack on Hooker’s fortified position was imprudent due to their strength and to meet the threat of Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps which had crossed the Rappahannock and was poised to threaten his rear. [59] Despite having a massive superiority over Stuart’s Corps to his front, with First and Fifth Corps fresh, Hooker had given up the fight and made no attacks against Stuart and made no move to attempt a junction with Sedgwick, instead begging him for support. That night Hooker called a council of war with his commanders supposedly to seek their advice on what to do. Though he surveyed them, with their opinion being split, Hooker had already decided to withdraw. “Couch and Reynolds considered it laughable that they had been called together when Hooker had already decided to retreat regardless of their opinion.” [60] Couch was disgusted with Hooker and feared what might happen if he continued to direct operations south of the river, and though wanting to take the offensive decided voted for immediate retreat. Sickles was sick at heart and hated the idea of retreat but he realized that Joe Hooker was spent as a commander, and that “if the Army of the Potomac remained south of the Rappahannock under Hooker’s command it simply would be served up for slaughter at Lee’s hands, Sickles voted with Couch.” [61] During the discussion Sickles gave his friend Hooker a measure of support, more for political and strategic reasons than tactical, offering the idea that European governments might support the Confederacy if the army was destroyed, and that the peace Democrat Copperheads had made significant gains in the last election and further defeat could not be chanced.

The army withdrew over the Rappahannock under the cover of darkness and fog the next morning, but the river overflowed its banks necessitating a halt until the morning of the May 6th, but Lee did not attack, he had to redeploy his forces and between the exhaustion of his soldiers and the weather on the 5th he had to postpone the attack. When Dorsey Pender reported that his scouts had found the Federals had crossed the Rappahannock and recovered their pontoon bridges, Lee erupted, “This is the way you young men are always doing…. You have again let these people get away. I can only tell you what to do, and if you do not do it it will not be done.” [62]

The army marched back to Falmouth when they had begun, most soldiers not understanding why they had to retreat when they had such a strong position. 40,000 Federal soldiers never saw action as Hooker squandered his advantage when he lost his nerve. During the heat of the fighting on May 3rd First and Fifth Corps faced no Confederates, and remained away from the battle while the Second, Third, and Twelfth Corps battled for their lives against the Confederates. “If the First Corps, under Reynolds, the Fifth, under Meade, had advanced on Stuart’s left flank and rear, defeat would have been turned into victory.” [63] Confederate General Harry Heth who commanded a brigade at Chancellorsville, wrote:

“It has always been my opinion that with the superiority of number of Hooker that Jackson could have been crushed: and the forces under General Lee should have met the same fate after Jackson was destroyed, as Hooker’s army lay between the two forces, and which could or should have virtually ended the war.” [64]

George Meade spoke for many when he said he was “fatigued and exhausted with a ten-days’ campaign, pained and humiliated at its unsatisfactory result.” [65] Overall, the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac blamed Hooker and Howard for their defeat, the believed that Hooker had been whipped, but not them. Their attitude would carry with them to Gettysburg.

Union Soldiers Retreating Across the Rappahannock

Abraham Lincoln probably took the defeat the hardest. Upon hearing the news he told Noah Brooks, a reporter who was visiting the White House, “My God! my God! What will the country say! What will the country say.” [66] Sickles gave one of the most accurate and dispassionate analysis of the battle, noting, “No strategic advantage of any importance was gained by either side.” [67]

Sickles “was lauded in the papers by editors who had once vilified him, and he was noted as a soldier who showed skillfulness in battle.” [68] The newspaper reports were only partially correct. Third Corps lost 4,119 soldiers killed, wounded, missing, or captured, the highest percentage of any Corps in the Army, and nearly a quarter of the total lost. It would be restructured from three to two very large divisions. Third Corps had fought hard, but, Sickles performance was uneven, after all he was not a professional soldier. He displayed particular gallantry under fire, and inspired his men. He acted aggressively except when directly obeying Hooker’s orders to be cautious. His biggest mistake, which was not entirely his own was in identifying the movement of Jackson’s rear guard on May 2nd as a withdraw. On the other hand he and Pleasanton had helped halt the Confederate attack that night, and the defensive effort showed that he was willing to fight when others fled.

Stonewall Jackson died on May 10th at a farmhouse at Guinea Station north of Richmond in the presence of his wife and infant daughter. All were comforted by the General’s religious faith and as he drew close to death all talk was of his passing and going to heaven, before he went into a delirious state, calling out, “Order A.P. Hill to prepare for action! Pass the infantry to the front….Tell Major Hawks-” and then his voice trailed off the war behind him. His last words, were spoken in a tone of relief, “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.” [69] Robert E. Lee never visited him while wounded or attended his funeral at the Virginia Military Institute.

To be continued…

Notes

[1] Wert, Jeffry. D., The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, New York, NY. 2005 p.230

[2] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible, Stan Clark Military Books, Gettysburg. PA. 1981 p.178

[3] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, Mariner Books, New York, NY. 1996 pp.145-151

[4] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, a Narrative: Volume II, Fredericksburg to Meridian, Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, New York, NY. 1963 & 1986 p.266

[5] Pinchon, Edgcum, Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and Yankee King of Spain, Doubleday, Doran, and Company, Garden City, NJ. 1945 p.172-173

[6] Wert, Jeffry. D., The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac, p.229

[7] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, p.151

[8] McPherson, James, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York, 1998 p.639

[9] Bates, Samuel P., Hooker’s Comments on Chancellorsville, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III based upon the The Century War Series of The Century of Magazine, Castle, Secaucus, NJ. p.219

[10] Alexander, Edward Porter, Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative, Acheron Press, 1907 Amazon Kindle Edition, Location 5230

[11] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, a Narrative: Volume II, Fredericksburg to Meridian, p.270

[12] Pleasanton, Alfred, The Successes and Failures of Chancellorsville, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III based upon the The Century War Series of The Century of Magazine, Castle, Secaucus, NJ. p.174

[13] Hebert, Walter H., Fighting Joe Hooker, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE. 1999 p.197

[14] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, a Narrative: Volume II, Fredericksburg to Meridian, p.278

[15] Pleasanton, Alfred, The Successes and Failures of Chancellorsville, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III p.176

[16] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, p.226

[17] Stine, J. H., History of the Army of the Potomac, J.B. Rogers Printing Company, Philadelphia, PA, p.342

[18] Hebert, Walter H., Fighting Joe Hooker, p.199

[19] Pinchon, Edgcum, Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and Yankee King of Spain, p.175

[20] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible, p.181

[21] Wert, Jeffry. D., The Sword of Lincoln: The Army of the Potomac, p.239

[22] Wert, Jeffry D., A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863, Simon and Schuster, NewYork, NY 2011 p.191

[23] Keneally, Thomas, American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles, Anchor Books, New York, NY. 2002 p.266

[24] Wert, Jeffry D., A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863, p.192

[25] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible, p.182

[26] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, a Narrative: Volume II, Fredericksburg to Meridian, pp.289-290

[27] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, p.226

[28] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, a Narrative: Volume II, Fredericksburg to Meridian, p.291

[29] Pleasanton, Alfred, The Successes and Failures of Chancellorsville, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III pp.177-179

[30] Smith, James Power, Stonewall Jackson’s Last Battle, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III based upon the The Century War Series of The Century of Magazine, Castle, Secaucus, NJ. p.208

[31] Howard, Oliver O., The Eleventh Corps at Chancellorsville, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III based upon the The Century War Series of The Century of Magazine, Castle, Secaucus, NJ. p.197

[32] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, pp.263-264

[33] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, p.269

[34] Carpenter, John A., Sword and Olive Branch: Oliver Otis Howard, Fordham University Press, New York, NY, 1999 p.47

[35] Collins, John L. When Stonewall Jackson Turned Our Right, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III based upon the The Century War Series of The Century of Magazine, Castle, Secaucus, NJ. p.184

[37] Pinchon, Edgcum, Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and Yankee King of Spain p.181

[38] Pinchon, Edgcum, Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and Yankee King of Spain p.181

[39] Pleasanton, Alfred, The Successes and Failures of Chancellorsville, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III p.179

[40] Stine, J. H., History of the Army of the Potomac, p.352

[41] Stine, J. H., History of the Army of the Potomac, pp.355-356

[42] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, p.287

[43] Catton, Bruce, Never Call Retreat, Washington Square Press, published by Pocket Books, New York, NY 1965 p.148

[44] Wert, Jeffry D., A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863 p.194

[45] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, a Narrative: Volume II, Fredericksburg to Meridian, p.303

[46] Cleaves, Freeman, Meade of Gettysburg, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 1960 p.109

[47] De Trobriand, Regis, translated by George K. Dauchy, Four Years With the Army of the Potomac 1867 p.425

[48] Pinchon, Edgcum, Dan Sickles: Hero of Gettysburg and Yankee King of Spain p.185

[49] Alexander, Edward Porter, Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative, location 6774

[50] Hebert, Walter H., Fighting Joe Hooker, p.211

[51] Stine, J. H., History of the Army of the Potomac, p.353 The actual number was 31 guns.

[52] De Trobriand, Regis, Four Years With the Army of the Potomac, p.445

[53] Swanberg, W.A., Sickles the Incredible, p.186

[54] Pleasanton, Alfred, The Successes and Failures of Chancellorsville, in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume III p.182

[55] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, p.325

[56] Stine, J. H., History of the Army of the Potomac, p.365

[57] De Trobriand, Regis, Four Years With the Army of the Potomac, pp.448-449

[58] Wert, Jeffry D., A Glorious Army: Robert E. Lee’s Triumph 1862-1863 p.200

[59] Alexander, Edward Porter, Military Memoirs of a Confederate: A Critical Narrative, location 6975

[60] Hebert, Walter H., Fighting Joe Hooker, p.218

[62] Sears, Stephen W., Chancellorsville, p.430

[63] Stine, J. H., History of the Army of the Potomac, p.367

[64] Stine, J. H., History of the Army of the Potomac, p.396

[65] Cleaves, Freeman, Meade of Gettysburg, p.114

[66] Goodwin, Doris Kearns, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, Simon ans Schuster Paperbacks, New York, NY. 2005 p.520

[67] Hessler, James A. Sickles at Gettysburg Savas Beatie New York and El Dorado Hills CA, 2009, 2010 p.64

[68] Knoop, Jeanne W., “I Follow the Course, Come What May” Major General Daniel Sickles, USA: A Biographical Interpretation From A Woman’s Point of View, p.92

[69] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, a Narrative: Volume II, Fredericksburg to Meridian, p.319

Exhaustive reporting in an a subject that is way over my head.

I had to google Stonewall Jackson just to determine he was a Confederate.

I had no idea. Apparently I had him confused with President Andrew Jackson.

I was appointed to a public high school name in honor of Andrew Jackson

in a mostly minority student body in Queens County. Any idea what anyone

would choose that name to honor such a dubious and confusing entity, when

in fact they were two completely different historical figures.

From your telling, it appears that Stonewall was the more noteworthy.

I remember the song "The Battle of New Orleans", and mention of Jackson,

who "fought the bloody British..." and not much else. I now learn that he was impeached,

but retained his office by a narrow margin.

I didn't understand Sickles role in this chapter. I got lost in the woods.

But as you can see, I was interested enough to dig deeper!