“The First Duty” Why I Wrote “Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: Religion and the Politics of Race in the Civil War Era and Beyond

The Preface to the Book

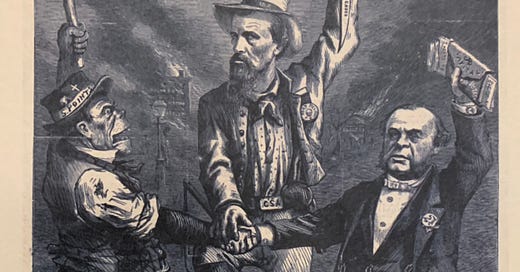

This Is a White Man’s Government. “We regard the Reconstruction Acts (so called) of Congress as usurpations, and unconstitutional, revolutionary, and void.”— Drawing by Thomas Nast. From Harper’s Weekly, September 1868. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, lc-dig-ppmsca-71958.

I am still traveling but taking the day off to rest with our friends while Judy makes fresh Pico de Gallo salsa for this evening. She’s making hot and mild versions from a variety of peppers, cilantro, tomatoes, tomatillos, onions, and garlic. It smells and tastes awesome, but I digress. Friday night I received an email from an old German friend, we have known each other almost 40 years and he and his wife are dear friends. He asked how he could get my book, which is available in Germany, but without a German translation. So I decided to work on translating it with the help of Google translate and email it to him.

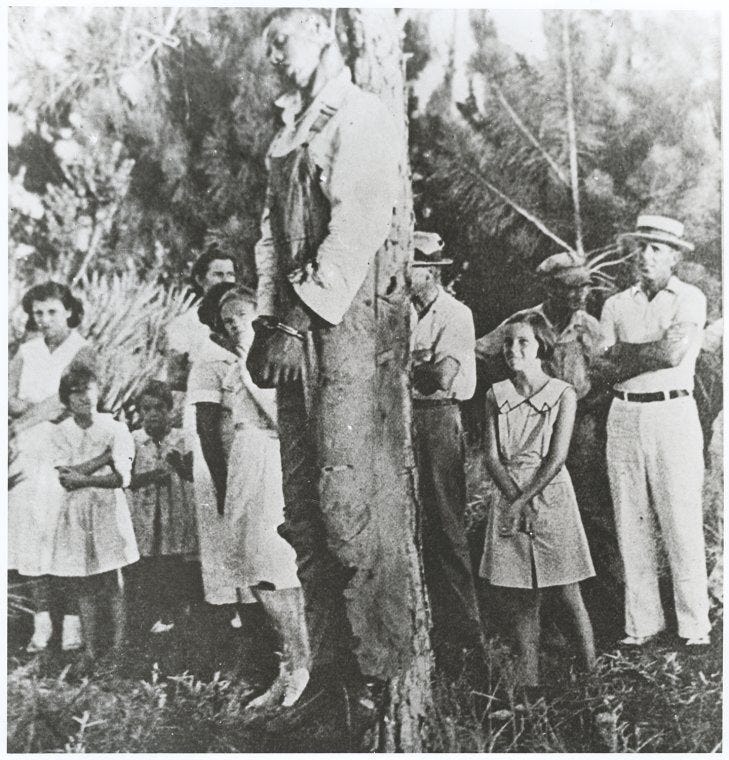

After I emailed it to him, I realized that in light of Florida’s new law prescribing standards for teaching History and Social Studies which describe slavery as a positive for enslaved Blacks, and completely ignoring the Black Codes, Jim Crow, Lynching, and the wholesale violence committed against Blacks, including massacres and the destruction of Black townships and neighborhoods, that the preface of Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory might be in order. I know that some of my readers have read it, but for those who haven’t I hope that by reading the introduction others will purchase it, and possibly subscribe to Dedicated to the Proposition that all Men are Created Equal.

Thank you for reading and enjoy you day.

The First Duty

The twenty-third century is an odd place to begin a book about events that were set in motion in the early seventeenth century. I am a historian, retired career military officer, and priest. As a historian I believe the truth, even when uncomfortable or damning, should be told. I take as inspiration a statement by Sir Patrick Stewart, in his role as Captain Jean Luc Picard, in the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode “The First Duty.” In the story Picard tells Cadet Wesley Crusher, “The first duty of every Starfleet officer is to the truth, whether it’s scientific truth or historical truth or personal truth! It is the guiding principle on which Starfleet is based.”

The distinguished history professor Timothy Snyder wrote, “To abandon facts is to abandon freedom.” [1] Truth matters, but it is human nature to take solace in myths and believe they are true. However, many myths are deadly. The deadliest include American Slavery’s “positive good,” the “Noble South,” the “Lost Cause,” the evils of Reconstruction, the good of Jim Crow, and the nonexistence of institutional racism in the United States.

These are lies so big and toxic that one has to call them whoppers. The “Noble South” and the “Lost Cause” are the same kind of lies that Adolf Hitler wrote of in Mein Kampf, using the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and the stab-in-the-back myth to eliminate enemies and engineer the Holocaust. They are intended to destroy truth and create alternative facts. Sissela Bok wrote:

Deceit and violence—these are the two forms of deliberate assault on human beings. Both can coerce people into acting against their will. Most harm that can befall victims through violence can come to them also through deceit. But the myths of “The Noble South” and “Lost Cause” are gargantuan lies perpetrated for over a century and a half that led to countless acts of violence and discrimination against Blacks. They are corrosive, destructive and an assault on the rights of all Americans. [2]

When I put what I read into the context of the era, the authors, and their motivations, I ask three questions: Why this? Why me? Why now? This helps to identify myths and falsehoods embedded in prior histories. The proper academic term for this is “historiography,” which I believe should be a required subject in all disciplines. As the late James Loewen observed,

Anyone who knows the history of the Civil War and its after- math and who talks with members of the public quickly grows frustrated. Most recent high school graduates, many history and social studies teachers, and even some professional histo- rians whose training is in other areas hold basic misconcep- tions about the era. Questions about why the South seceded, what the Confederacy was about, and the nature of its symbols and ideology often give rise to flatly untrue “answers.” In turn these errors persist because most Americans do not know or have not read key documents in American history about the Confederacy. [3]

Another tool is hermeneutics:

A methodology of interpretation is concerned with problems that arise when dealing with meaningful human actions and the products of such actions, most importantly texts. . . . The crucial point, then, is that any text has an envisioning historical and cultural context and the context of a text is not simply textual. . . . After all, texts inevitably have a setting—historical, cultural, authorial—on which their actual meaning is critically dependent. [4]

This is particularly important in interpreting the history of American slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and South- ern redemption. Much of what we regard as history is based on the twin myths of the “Noble South” and the “Lost Cause,” which, in addition to being crude but effective revisionist his- tory and propaganda, act in a similar manner to religious texts. Facts are ignored, and biography becomes hagiography, per- vaded by racist narratives. So, it is important for those who read them to use historiography and hermeneutics to differentiate truth from fiction.

An escaped slave named Peter Gordon showing his scarred back at a medical examination in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. 1863. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Civil War Collection, lc-dig-ppmsca-54375.

Likewise, historical ignorance and the belief of myth becomes a problem when leaders who are indifferent history and immersed in rapidly changing situations, flaunt their ignorance. This is not new; previous world leaders were human beings, too, and humanity is the one constant in human his- tory. In the words of Barbara Tuchman, “Any person who considers himself, and intends to remain, a member of Western society inherits the Western past from Athens and Jerusalem to Runnymede and Valley Forge, as well as to Watts and Chicago of August 1968. He may ignore it or deny it, but that does not alter the fact. The past sits back and smiles and knows it owns him anyway.” [5]

Thucydides in his History of the Peloponnesian War wrote to inform “those who want to understand clearly the events which happened in the past, and which (human nature being what it is) will, at some time or in another and in much the same ways, be repeated in the future.” [6] But history proves its critics wrong in showing the consistency of human beings from one era to the next. Thus the “task of historians then does not seem too difficult to describe; it is to trace the ways in which people of Western culture have reflected on the past and what these revelations have told them about human life in the continuum of past, present, and future.” [7] As Williamson Murray wrote about Thucydides’s successors:

Notwithstanding, successors of the Hellenic soldiers and politicians about whom he wrote have repeatedly chosen to believe that they are different and that the lessons of the past are irrelevant to their unique circumstances. Why this remains so remains one of the mysteries of the human experience. Per- haps the most compelling explanation is simple generational transition, the conviction of each new crop of leaders assuming power are different from their predecessors and immune from their errors. To paraphrase an old saying, what is new is not new is not necessarily interesting and what is interesting is not necessarily new. Yet, political and political leaders seem driven to repeat the blunders of their predecessors. [8]

This book began as a short chapter in my Gettysburg Staff Ride text while I was on the faculty of the Joint Forces Staff College in Norfolk, Virginia. The persistent myths that serve as blinders to properly understanding the Civil War perplexed me, so I decided to research them and share my findings with my students, because military histories of the Civil War, its battles and leaders, often skim over racism and slavery, which is unsurprising, for they deal with strategy, campaigns and battles. But to understand the American Civil War, one has to tackle the elephant in the room that many people want to ignore: American slavery and racism. Slavery ended, but racism did not, and the lingering effects of both are alive and well in the United States.

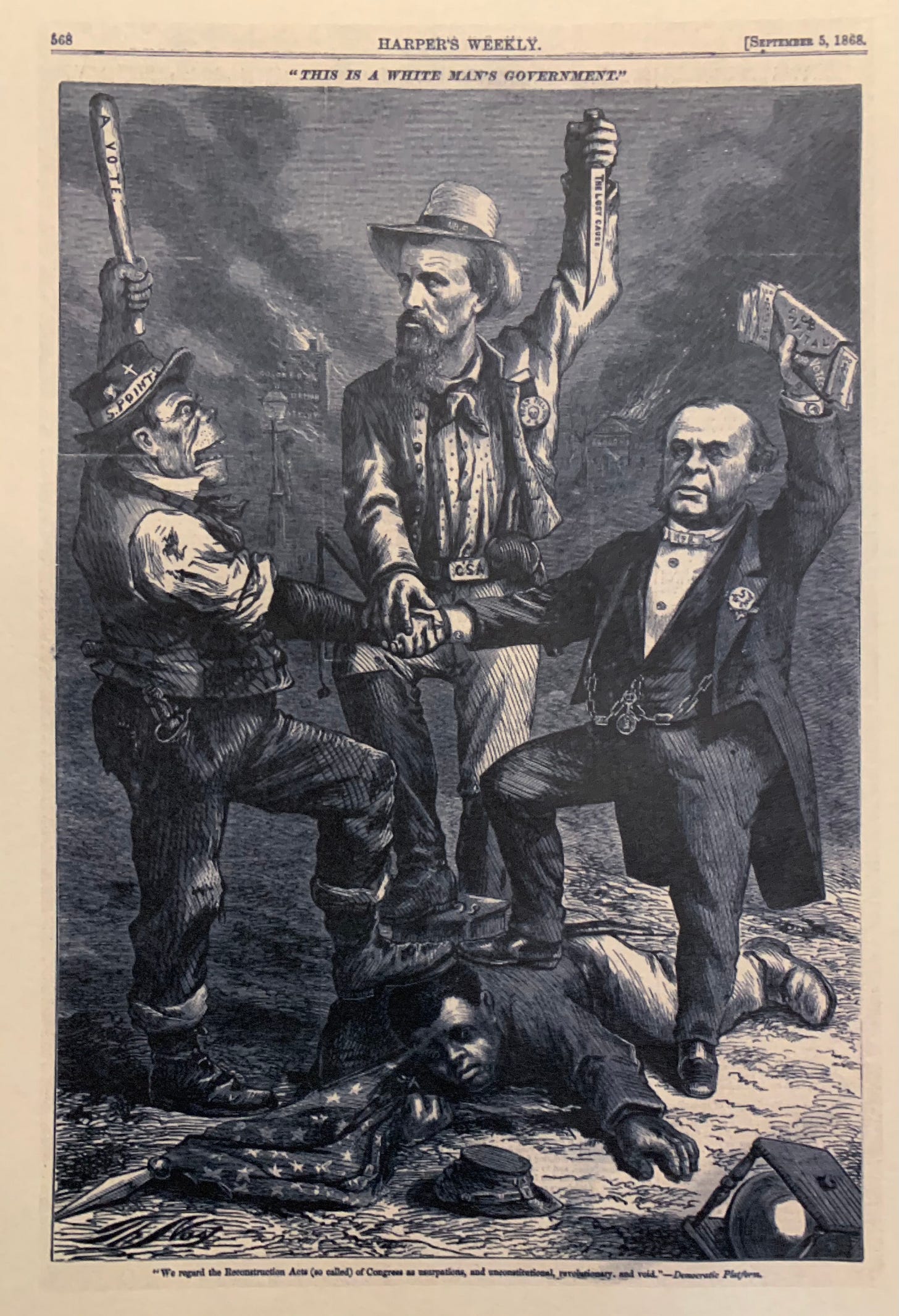

Cartoon, Decrying the Hamburg Massacre of July 1876. Thomas Nast. Harper’s Weekly, August 1873.

The propaganda mill of Noble South and Lost Cause proponents are a major problem, much like Holocaust deniers. Therefore, they must be confronted in ways that may seem impolitic. Nevertheless, their falsehoods must be exposed. Systemic institutional racism and discrimination has impacted almost every aspect of American life, religion, and culture since the first Blacks landed at Jamestown in 1619. It was true then and is true now, for the past is not always past—or, as Mark Twain reportedly quipped, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

The Lost Cause was historic revisionism at its best. It became “history” because most Northerners wanted to leave the war behind and stopped caring about what happened to Blacks. Northern business interests exploited the situation for profit by working with former slave owners and Southern state gov- ernments to reenslave Blacks by other means.

The war was about how Americans’ views of liberty and slavery influenced their racial attitudes. To slavery supporters Blacks were an inferior or subhuman race, who could never be the equal of whites—not even human, but property. White supremacy and its web of systemic cultural, political, economic, and religious racism remains a powerful part of American life. This makes it difficult to confront racism without push- back by politicians, pundits, preachers, and militants, who, despite their denials, are as racist as any Klansman, Red Shirt, or White Liner.

In my choice of title and cover image, I wanted to emphasize the evil of the system and the role that Blacks played in abolition: Black soldiers who fought for their freedom and that of their still enslaved people; Blacks who fought against a racist insurgency during Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and the civil rights movement; and Blacks who continue the fight for equality today. The image on the cover is a photograph of Sergeant William Carney of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the most famous of the African American units of the war. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Battery Wagner in July 1863, which is commemorated in the film Glory. During the battle Carney was badly wounded but refused to let the American flag fall into the hands of the rebels. The picture of the proud Sergeant Carney posing in his uniform with the flag captures something that many benevolent and sympathetic whites fail to grasp: for Blacks, emancipation and freedom are an extremely important and personal matter, one in which their ancestor’s efforts and sacrifices matter, and their unique insights and experiences are often disregarded.

The book’s title, Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory, is the first line of Julia Ward Howe’s“Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which was a favorite of Black soldiers serving in the Union Army. The hymn became an anthem as the aim of the war expanded from restoring the Union to emancipating slaves. When Black soldiers in theWilderness Campaignbegan to liberate fellow Blacks from slavery in Virginia, it increased the validity of their participation in the war. Black soldiers saw the war as a crusade for freedom with a profoundly theological meaning, akin to Moses leading the Hebrews out of Egypt during the Exodus. As Sergeant John Brock of the Forty-Third United States Colored Troops (USCT) Infantry Regiment wrote of his experience:

We have been instrumental in liberating some five hundred of our sisters and brothers from the accursed yoke of human bondage. . . . As several of them remarked to me, it seemed to them like heaven, so greatly did they realize the difference between slavery and freedom. . . . The slaves tell us they have been praying for these blessed days for a long time, but now their eyes witness their salvation from that dreadful calamity, slavery and, what more than they expected, by their own brethren in arms. What a glorious prospect it is to behold this glorious Army of Black man as they march with martial tread over the sacred soil of Virginia. [9]

The sacrifices and dedication of the Black soldiers who fought as members of the USCT and various state raised regiments had an impact a century later. The night before his assassination, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. He concluded with these words: “And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.” [10]

The book’s subtitle, Religion and the Politics of Race in the Civil War Era and Beyond, deals with how racism infects American history, from our colonial beginnings until today. Despite emancipation, citizenship, and suffrage, Blacks have seldom enjoyed the full benefits of equality, and throughout our his- tory Whites treated Blacks as less than human. The Christian religionwas a major factor in American racism and slavery. Southern ministers became the fiercest defenders of slavery, because rich plantation owners sat in their pews. Ideology was less defined; it was mostly racist, but it had economic and pseudoscientific aspects that supposedly proved that Blacks were inferior to whites. Unfortunately, much of this continues today.

Finally, the words and actions of the white supremacists and their defenders were connected to politics, before, during, and after the war. Slavery created a cult of racist true believers. According to Eric Hoffer,

It is the true believer’s ability to “shut his eyes and stop his ears” to facts that do not deserve to be either seen or heard which is the source of his unequaled fortitude and constancy. He cannot be frightened by danger nor disheartened by obstacles nor baffled by contradictions because he denies their existence. . . . And it is the certitude of his infallible doctrine that renders the true believer impervious to the uncertainties, surprises and the unpleasant realities of the world around him. [11]

Since we still contend with the lies of the Noble South and the Lost Cause, I write this book as my “first duty.” Immanuel Kant wrote: “It is a duty to tell the truth. The concept of duty is inseparable from concept of right. A duty is what one being corresponds to the rights of another. Where there are no rights there are no duties. To tell the truth is thus a duty: but only in respect to one who has the rights to the truth.” [12]

One editorial note: in my use of quotations from the period, I have not for the most part attempted to modernize the English, correct the grammar, or change the colloquialisms used by the original writers. Likewise, I have left in the racist terms— which I find absolutely reprehensible—that the original writers used, in order that the reader experiences the truth of just how deeply racism was embedded in an often mythical American history. I do it also to remind us why many, especially American Blacks and other racial minorities, are offended when those terms are used today. By doing this I preserve the unvarnished history, and I allow the reader to have an emotional gut reaction that they might not otherwise have. A healthy revulsion regarding the crimes against humanity committed by our ances- tors is not a bad thing; perhaps if it were taught and received in the proper spirit, we might have the kind of personal reck- oning that would prevent their repetition. Unfortunately, it seems that given the resistance to anything approaching it in our current political and religious climate, such a reckoning will be unlikely for at least another generation.

Notes

1. Snyder, On Tyranny, 63.

2. Bok, Lying, 18.

3. Loewen and Sebasta, Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader, 3.

4. “Hermeneutics,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed July 20,

2020, http://Plato.stanford.edu/entries/hermeneutics/#Textline.

5. Tuchman, Practicing History, 268.

6. Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 48.

7. Breisach, Historiography, 3.

8. Murray, Past as Prologue, 2–3.

9. Trudeau, Like Men of War, 212.

10. King, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.”

11. Hoffer, True Believer, 79.

12. Bok, Lying, 268.