The Most Glorious Fourth: July 4th 1863, Gettysburg, Vicksburg and the Renewal of the Proposition that All Men are Created Equal

Tonight I am posting a final section of my Gettysburg Staff Ride Text. It is appropriate for the 297th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. It is that of July 4th, 1863, the 87th anniversary of that document, by at the time it was an independence that was threatened by a rebellious race based police state, that as it fought to destroy the Union and enforce its racism on the Free States that remained loyal to the Union. During the Gettysburg campaign, an estimated 250 Blacks from Franklin County were seized and taken south to be enslaved or re-enslaved.

Therefore the contexts of the Union victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Port Hudson, and Helena have to be measured in light of the defeat of Confederate armies determined to destroy the Union and make slavery the law of the land from the Atlantic to the Pacific. If one only sees them in a purely military sense they miss the more important part of the equation. The military victories ensured that without an electoral defeat of Lincoln by the Copperhead “Peace Democrats” in the election of 1864 there could be no Confederate victory or independence based on a negotiated peace agreement.

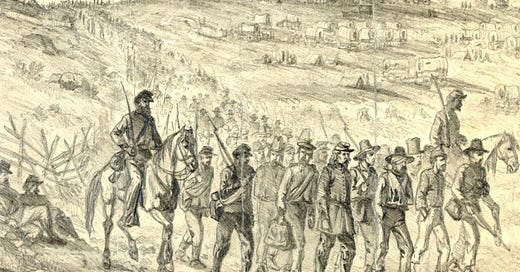

Confederate prisoners of Longstreet’s Corps (Edwin Forbes)

Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia tried to lick its wounds and regroup following its last disastrous attacks on 3 July 1863. It prepared hasty fortifications on Seminary Ridge in case Meade’s Army of the Potomac attempted to attack on July 4th, but that attack would not come. Meade had no inclination of allowing the Confederates to do to his forces what his did to Lee’s army at Pickett’s Charge. Between the two armies lay tens of thousands or dead, dying, and grievously wounded and maimed soldiers.

A Union soldier, Elbert Corbin, Union Soldier at Gettysburg 1st Regiment, Light Artillery, N. Y. S. Volunteers (Pettit’s Battery) wrote of the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg:

“Dead men and plenty here – and I saw plenty of them in all shapes on the field – Help to wound & Kill men then Patch them up I could show more suffering here in one second than you will see in a Life…” [1]

Long after the Battle, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, who commanded the 20th Maine in its defense of Little Round Top, said:

“In great deeds something abides. On great fields something stays. Forms change and pass; bodies disappear, but spirits linger, to consecrate ground for the vision-place of souls.” [2]

The ground was consecrated by the blood of the men who fell there, and like Chamberlain whenever I visit the hallowed ground of Gettysburg I have a sense that the spirits of those men still linger.

On the morning of July 4th, “The day after the battle began muggy and cloudy, and there was a tremendous rainstorm” [3] as the Army of Northern Virginia and Army of the Potomac licked their wounds on the bloodstained Gettysburg battlefield. Both armies had suffered severely in the fighting and around 50,000 soldiers from both sides lay dead, dying, or wounded on the battlefield. It was a somber day, the sweltering heat sunshine which had bathed the battlefield as Longstreet’s’ Corps attacked Cemetery Ridge was now broken by heavy rain and wind. The commanders of both armies, General Robert E. Lee and Major General George Meade attempted to discern the others intent while making their own plans.

Early in the morning of July 4th, or possibly very late the night of July 3rd, General Robert E. Lee called Brigadier General John Imboden to his headquarters to discuss the withdrawal of the Army of Northern Virginia from the place of its defeat. Lee had spent the evening of July 3rd with James Longstreet. They “rode together along the lines on Seminary Ridge and conferred with other generals.” [4]

When Lee arrived to meet Imboden the brigadier felt the need to say something and said to Lee: “General, this has been a hard day on you.” [5] Lee waited sometime before replying mournfully, “Yes, it has been a sad, sad day for us” [6] and then Lee praised the conduct of Pickett’s men saying “I never saw troops behave more magnificently than Pickett’s division of Virginians did today in that grand charge upon the enemy.” He continued and lamented what he believed to be the lack of support from the rest of the army, then paused and “exclaimed in a voice that echoed loudly and grimly through the night, “Too bad! Too bad! Oh, too bad!” [7] It was a strange thing to say, and it showed Lee’s inability to comprehend the strength and tenacity of his opponent on that final day of battle, and how many of Lee’s decisions, including the fact that “he had denied Hill’s permission to throw his whole corps into the assault,” [8] contributed to his defeat.

Lee realized, that unless “he could somehow entice Meade into counterattacking along his Seminary Ridge line, he must get the army back to Virginia with all speed. There was only enough ammunition for one battle, if that…and lee had to consider that Meade might aggressively seek to cut the routes south to the Potomac.” [9] Thus he wasted little time in preparing the army for its return. Lee “chose his routes, decided on the order of march, and then, despite the lateness of the hour and his bone-deep weariness after three days of failure and frustration, went in person to make certain that his plans were understood by the responsible commanders.” [10] Lee indicated, not in his words, but in his actions, that he had been failed by his subordinates. But the fault did not lay with his subordinates, but rather with him. He did not clearly communicate his orders and expectations in detail to his new Corps commanders, Richard Ewell and A.P. Hill, who had never served directly under his command, and James Longstreet who constantly opposed what he believed would lead to disaster.

Likewise, Lee was finally aware that the method of command he had employed so successfully with Stonewall Jackson had failed, and in “the task of saving his army, he trusted no one with any discretion at all.” [11] Unlike “the vague and discretionary orders he had issued throughout the week leading up to battle and even during the past three days of fighting…his instructions were now written and precise….” [12]

Across the valley that separated the armies, Meade explained “that he had not wanted to follow “the bad example [Lee] had set me, in ruining himself attacking a strong position.” [13] By not attacking, Meade was probably correct, despite the criticism he received from contemporaries and later commentators. Lee’s army, though defeated was not broken and held good ground on July 4th, likewise, the lack of supplies, exhaustion of his troops, and foul weather would likely have doomed any attack. Instead he told a cavalry officer “We have done well enough…” [14]

At about 1:00 P.M. on July, 4th, Imboden’s troopers began their unenviable mission of escorting the ambulance trains carrying the wounded. As they did “a steady, pounding rain increased Imboden’s problems manifold, yet by 4 o’clock that afternoon he had the journey underway. He estimated this “vast procession of misery” stretched for seventeen miles. It bore between 8,000 and 8,500 wounded men, many in constant, almost unendurable agony as they jolted over the rough and rutted roads.” [15] Although beaten, Lee’s army “retained confidence in itself and its commander” [16] and they retreated in good order.

Across the carnage strewn battlefield on Cemetery Ridge George Meade took inventory and “unsure about the nature and extent of Lee’s movements from information he had already received, he realized he had a busy day ahead.” [17] The army, tired from three weeks of hard marching and three days of brutal combat was exhausted; Meade’s was down to about “51,000 men armed and equipped for duty.” About 15,000 soldiers were loose from the ranks, and though they would return “for the moment they were lost.” [18] The torrential rain “was a damper on enthusiasms,” and the Federal burial parties, exhausted from the battle and engaged in somber work, “dug long trenches and, after separating Rebel from Yankee, without ceremony piled the bodies several layers deep and threw dirt over them.” [19]

Meade ordered his trains to bring the supplies from Westminster Maryland on the morning of July 4th as Federal patrols pushed into the town to see what Lee’s army was doing, but apart from isolated skirmishing and sniper actions, the day was quiet. During the afternoon, “David Birney summoned the band of the 114th Pennsylvania “to play in honor of the National Anniversary” and up on the “line of battle.” They played the usual “national airs, finishing with the Star Spangled Banner.” [20] As they did a Confederate artillery shell passed over them, and with that last shot the battle of Gettysburg was over. Meade, signaling the beginning of an overly cautious pursuit, wired Halleck: “I shall require some time to get up supplies, ammunition, etc. [and to] rest the army, worn out by hard marches and three days of hard fighting.” [21]

Surgeons and their assistants manned open-air hospitals while parties of stretcher-bearers evacuated wounded men for treatment and other soldiers began to identify and bury the dead. A Confederate soldier described the scene west of the town on July 4th:

“The sights and smells that assailed us were simply indescribable-corpses swollen to twice their size, asunder with the pressure of gases and vapors…The odors were nauseating, and so deadly that in a short time we all sickened and were lying with our mouths close to the ground, most of us vomiting profusely.” [22]

Confederate Dead at Gettysburg

Surrendered Confederate soldiers, civilians, and freed slaves watch Grant’s Army march into Vicksburg on July 4t, 1863 (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper)

Halfway across the continent Confederate Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton surrendered his emaciated forces at Vicksburg to Major General Ulysses S Grant. The victory cut the Confederacy in half.

The triumphant news of Grant’s victory soon reached the White House. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells was the first to receive the news via a telegram from Admiral David Dixon Porter whose Mississippi Squadron had executed with Grant one of the first truly joint operations in American history. Wells hurried to the White House where Lincoln was speaking with Salmon Chase and several others. Wells reportedly “executed a double shuffle and threw up his hat by way of showing that he was the bearer of glad tidings.” Mr. Lincoln affirmed that “he never saw Mr. Welles so thoroughly exited as he was then.” [23]

Indeed it was a Glorious Fourth, from the Union point of view, as the “list of brilliant successes” scored by the Union, afloat and ashore, on the eighty-seventh anniversary of the nation’s birth.” [24] Not only had the Rebels been defeated at Vicksburg and Gettysburg, but at Helena and Port Hudson on the Mississippi where their attacks on small Union forces were repulsed with heavy casualties, after which Port Hudson fell to General Nathaniel Banks’s army. Wells recorded:

“The elated President “caught my hand… and throwing his arm around me, exclaimed: ‘what can we do for the Secretary of the Navy for this glorious intelligence - He is always giving us good news. I cannot, in words, tell you my joy over this result. It is great, Mr. Wells, it is great!’ With the fall of Vicksburg, as Lincoln later said, “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea.” [25]

Confederate Chaplain William Lovelace Foster, of the 35th Mississippi also referred to the “Father of Waters”:

“And thou great Father of Waters upon whose lovely banks I have stood as sentinel in the lonely watches of the night… no more shall I guard thy rolling waves nor walk up and down thy friendly banks. They proud waves, unguarded by Southerners, shall now roll on to the mighty ocean upon to friendly errand but for us beating upon thy placid bosom the power and wrath of our deadly foes.” [26]

Grant wrote of the news of Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg combined with his victory over Confederate General John Pemberton’s army at Vicksburg:

“This news, with the victory at Gettysburg won the same day, lifted a great load of anxiety from the minds of the President, his Cabinet and the loyal people all over the North. The fate of the Confederacy was sealed when Vicksburg fell. Much hard fighting was to be done afterwards and many precious lives were to be sacrificed; but the MORALE was with the supporters of the Union ever after.” [27]

Grant also wrote about what happened after the defeated Confederates laid down their arms:

“Logan's division, which had approached nearest the rebel works, was the first to march in; and the flag of one of the regiments of his division was soon floating over the court-house. Our soldiers were no sooner inside the lines than the two armies began to fraternize. Our men had had full rations from the time the siege commenced, to the close. The enemy had been suffering, particularly towards the last. I myself saw our men taking bread from their haversacks and giving it to the enemy they had so recently been engaged in starving out. It was accepted with avidity and with thanks.” [28]

It was a fitting day of remembrance as it was the 87th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and the significance was not lost on any of the commanders. Grant, the victor of Vicksburg had eliminated a Confederate army of over 33,000 troops, and William Tecumseh Sherman wired his friend a most appropriate message: “This is a day of jubilee, a day of rejoicing for the faithful.” [29]

On the evening of July 7th Lincoln appeared before a cheering crowd gathered at the White House and delivered an impromptu speech. He believed that the Declaration of Independence was of special importance because the nation was dealing with “a gigantic rebellion, at the bottom of which is an effort to overthrow the principle that all men are created equal.” He referred to the Confederate armies as “the cohorts of those who oppose the declaration that all men are created equal.” [30]

Back in Gettysburg, Lieutenant Elisha Hunt Rhodes of the 2nd Rhode Island wrote:

“Was ever the Nation’s Birthday celebrated in such a way before. This morning the 2nd R.I. was sent out to the front and found that during the night General Lee and his Rebel Army had fallen back. It was impossible to march across the field without stepping upon dead or wounded men while horses and broken artillery lay on every side.” [30]

As Lee withdrew Meade slowly pursued and lost his chance of trapping the Confederate Army before it could escape across the rain-swollen Potomac River. Lee completed his withdrawal under pressure on July 14th as his rear-guard under the command of Major General Harry Heth fought a delaying action against Union forces in which the accomplished academic and author Brigadier General Johnston Pettigrew was mortally wounded.

Meade’s lackluster pursuit was criticized by many including President Lincoln who believed that had Meade been more aggressive that the war could have ended there. Had Lee’s army been destroyed in little over a week after the surrender of Vicksburg it could have well brought about the downfall of the Confederacy in the summer of 1863. Newspaperman Noah Brooks wrote that Lincoln’s grief and anger at Lee’s escape “were something sorrowful to behold” while Lincoln’s secretary, John Hay recorded Lincoln saying “We had them within our grasp. We had only to stretch out our hands and they were ours.” Lincoln penned a letter to Meade that he never sent, but word of his anger reached the General who offered his resignation, but Henry Halleck calmed Meade and refused to accept his resignation. Instead, Meade was promoted to Brigadier General in the Regular Army. [31] After a few days, Lincoln’s anger abated and he reconsidered his view of Meade. He told one of Meade’s generals “I am now profoundly grateful for what has been done, without criticism for what was not done. Gen. Meade has my confidence as a brave and skillful man, and a true man.” [32]

Lincoln’s anger and frustration were understandable but somewhat unfair to Meade who was still new to command of an army that had sustained heavy casualties and which was exhausted from over a month of hard marching and campaigning. Additionally, Meade was without two of his best Corps commanders, the dead John Reynolds, and the severely wounded Winfield Scott Hancock, to whom much of the success at Gettysburg was owed.

Even so, the skill of Meade in defeating Lee at Gettysburg was one of the greatest achievements by a Union commander during the war in the East. In earlier times Lee had held sway over his Federal opponents. McClellan, Porter, Pope, Burnside and Hooker had all failed against Lee and his army.

Many of the dead at Gettysburg were the flower of the nation. Intelligent, thoughtful and passionate they were cut down in their prime. The human cost of over 50,000 men killed or wounded is astonishing. In those three days more Americans were killed or wounded than in the entire Iraq campaign. Compared to Gettysburg, Grant’s victory at Vicksburg had cost the Union under 1,000 dead and 2,000 wounded.

The war would go on for almost two more years adding many thousands more dead and wounded. However the Union victory at Gettysburg was decisive. Never again did Lee go on the offensive. When Grant came east at the end of 1863 to command Union armies in the East against Lee the Federal armies fought with renewed ferocity and once engaged Grant never let Lee’s forces out of his grip.

Notes

[1] Corbin, Elbert. Union soldier in Pettit’s Battery account of caring for wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg retrieved from https://www.gilderlehrman.org/sites/default/files/inline-pdfs/t-03685.pdf 18 July 2014

[2] Primono, John W. The Appomattox Generals: The Parallel Lives of Joshua L Chamberlain, USA, and John B. Gordon, CSA, Commanders at the Surrender Ceremony of April 12th 1865 McFarland and Company Publishers, Jefferson NC 2013 p.187

[3] Catton, Bruce The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road Doubleday and Company, Garden City New York, 1952 p. 322

[4] Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet The Confederacy’s Most Controversial Soldier, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster, New York and London 1993 p. 293

[5] Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage, Harper Collins Publishers, New York 2002 p.530

[6] Freeman, Douglas Southall, Lee an abridgment by Richard Harwell, Touchstone Books, New York 1997 p. 341

[7] Freeman Lee p. 341

[8] Foote, Shelby, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two Fredericksburg to Meridian Random House, New York 1963 p. 581

[9] Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston and New York 2003 p. 470

[10] Foote, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two pp.579-580

[11] Dowdy, Clifford. Lee and His Men at Gettysburg: The Death of a Nation Skyhorse Publishing, New York 1986, originally published as Death of a Nation Knopf, New York 1958

[12] Foote, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.580

[13] McPherson, James. The Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1988 p.663

[14] McPherson The Battle Cry of Freedom p.663

[15] Sears Gettysburg pp.471-472

[16] Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command, A Touchstone Book, Simon and Schuster New York, 1968 p.536

[17] Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign p.535

[18] Catton The Army of the Potomac: Glory Road p.323

[19] Sears Gettysburg p.474

[20] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg: The Last Invasion Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 2013 pp.433-434

[21] Schultz, Duane The Most Glorious Fourth: Vicksburg and Gettysburg July 4th 1863. W.W. Norton and Company New York and London, 2002 pp.355-356

[22] _________ What Happened to Gettysburg’s Confederate Dead? The Blog of Gettysburg National Military Park, retrieved from http://npsgnmp.wordpress.com/2012/07/26/what-happened-to-gettysburgs-confederate-dead/ 18 July 2014

[23] Goodwin, Doris Kearns, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, New York, NY. 2006 p.533

[24] Foote, The Civil War, A Narrative. Volume Two p.606

[25] Goodwin, Team of Rivals, p.533

[26] Hoehling, A.A., Vicksburg: 47 Days of Siege. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA. 1996, p.283

[27] Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume One, p. 215

[28] Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume One p. 213

[29] Schultz, Duane The Most Glorious Fourth p.364

[30] Catton, Bruce. Never Call Retreat. Washington Square Press Publication of Pocket Books, a division of Simon and Schuster Inc. New York, NY. 1965, p.205

[31] Rhodes, Robert Hunt ed. All for the Union: The Civil War Diaries and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes, Vintage Civil War Library, Vintage Books a Division of Random House, New York 198

[32] Catton. Never Call Retreat p.202

[33] Goodwin. Team of Rivals, p.539

You succeed.

To understand the scope of Gettysburg without your writing would be incomplete at best.