The Promise and Tragedy of Appomattox

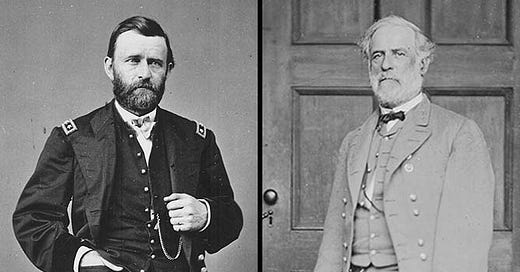

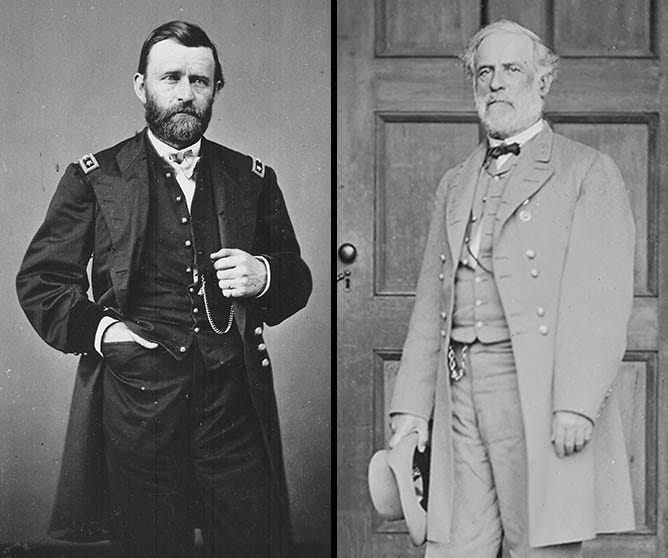

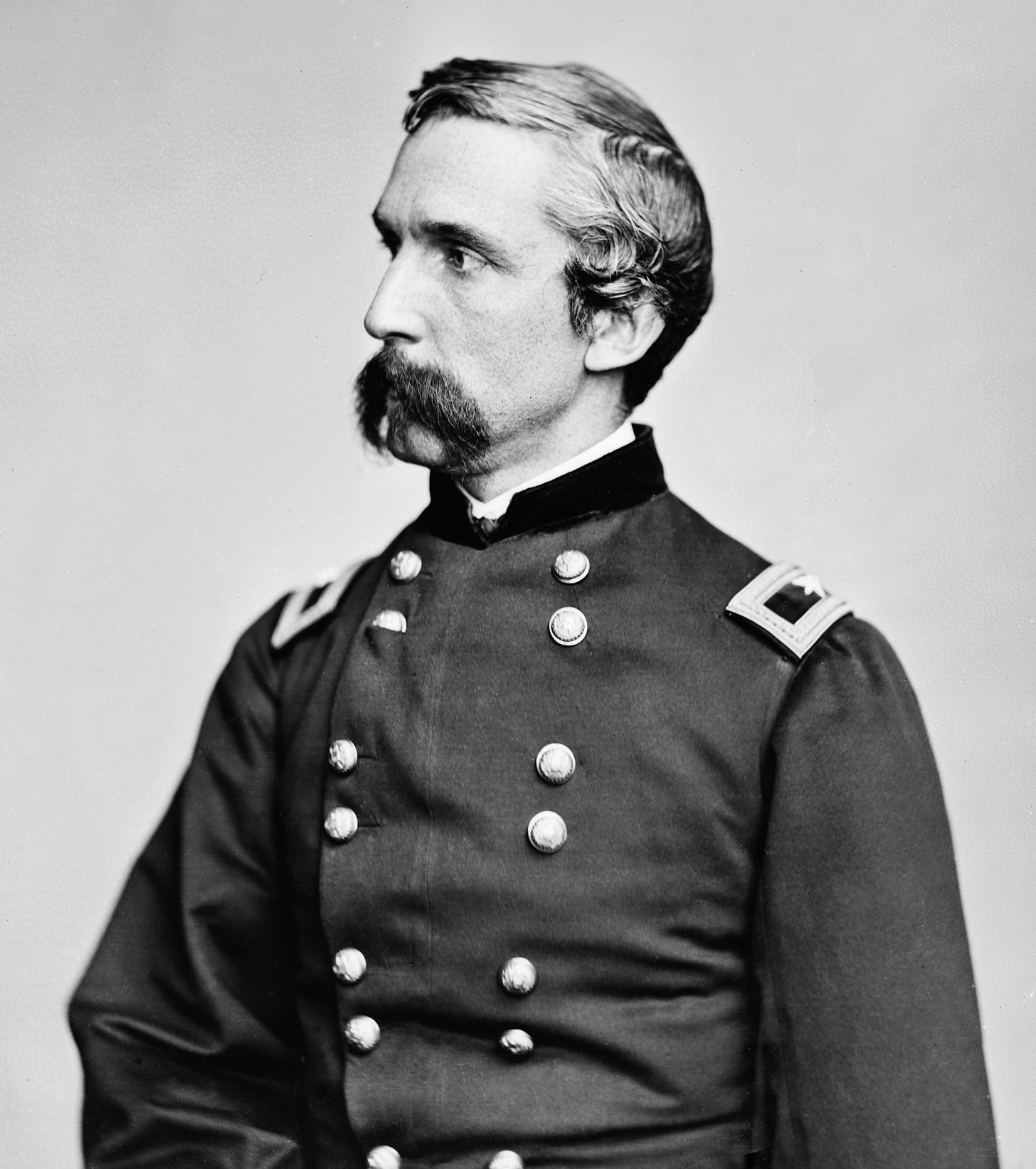

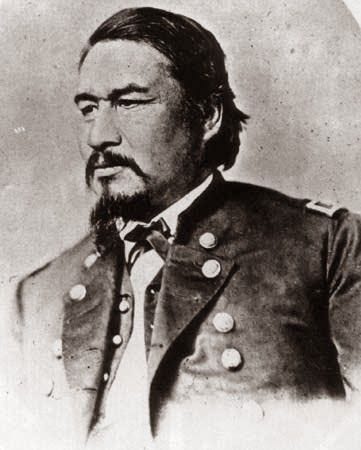

One hundred and fifty-eight years ago, on the 9th and 10th of April 1865, four men, Ulysses S Grant, Robert E. Lee, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, and Ely Parker, taught succeeding generations of Americans the value of mutual respect and reconciliation. The four men, each very different, would do so after a bitter and bloody war that had cost the lives of over 700,000 Americans and had left hundreds of thousands others maimed, or without a place to live, and seen vast swaths of the country ravaged by war.

The differences between the men, their upbringing's and their views about life seemed to be insurmountable. Confederate General Robert E. Lee was the epitome of a Southern aristocrat and career army officer. He was a slave owner and resigned his commission as a Colonel in the United States Army to fight for the Confederacy and wage war against the Union. He led his army to costly victories and catastrophic defeats. Though a skilled Napoleonic tactician, he seldom took the counsel of his generals. He did not appreciate or adapt quickly to the technological changes that, throughout the war, had made Napoleonic tactics obsolete.

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, like Lee was a West Point graduate and veteran of the War with Mexico, but there the similarities ended. Grant was an officer of humble means who had struggled with alcoholism and failed in his civilian life after he left the army before returning to it as a volunteer when the war began. Grant was highly successful and a tenacious opponent. His victories in the West cut the Confederacy in two and were beginning to threaten the deep South when he was called East to command the Union armies, leaving the master of modern warfare, William Tecumseh Sherman to continue there, as he made camp with George Meade’s Army of the Potomac to grind Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia into dust.

Major General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain had been a professor of rhetoric and natural and revealed religion from Bowdoin College until 1862 when he volunteered to serve. He was a hero of Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg where he commanded the 20th Maine. He was grievously wounded at Petersburg, nearly dying from wounds that crippled him for life. He helped exemplify the importance of citizen soldiers in peace and war.

Finally, there was Colonel Ely Parker, a full-blooded Seneca Indian; a professional engineer by trade, a man who was barred from being an attorney because as a Native American he was never considered a citizen. Although he had been rejected from serving in the army for the same reason, his friend Grant obtained a commission and kept him on his staff.

By April the end was near. Sherman had cut through Georgia and by capturing Atlanta ensured the re-election of Abraham Lincoln and presented Charleston, South Carolina, the birthplace of the rebellion as a Christmas gift to Lincoln, before marching into North Carolina. Grant’s armies drove Lee’s battered army from Petersburg forcing Jefferson Davis and the Confederate government from Richmond, which was liberated by the U.S. Colored Troops of the Union XXV, Corps. Lee attempted to escape but Philip Sheridan’s cavalry and the Army of the Potomac cornered him at Appomattox.

Grant knew Lee’s position to be hopeless, and on April 7th he wrote Lee asking for his surrender.

“The result of the last week must convince you of the hopelessness of further resistance on the part of the Army of Northern Virginia in this struggle. I feel that it is so, and regard it as my duty to shift from myself the responsibility of any further effusion of blood, by asking of you the surrender of that portion of the C. S. Army known as the Army of Northern Virginia.”

Early on the ninth, after a final attack failed to break through Sheridan’s forces, Lee responded.

“I received your note of this morning on the picket-line, whither I had come to meet you and ascertain definitely what terms were embraced in your proposal of yesterday with reference to the surrender of this army. I now ask an interview in accordance with the offer contained in your letter of yesterday for that purpose.”

Lee was ushered through the Federal lines and met Grant at the house of Wilmer McLean, who had moved to Appomattox in 1861 after his home near Manassas had been used as a Confederate headquarters and was damaged by artillery fire. Lee was dressed in his finest uniform complete with sash, while Grant was dressed in a mud-splattered uniform and overcoat and only distinguished from his soldiers by the three stars on his should boards. Grant’s dress uniforms were far to the rear in the baggage trains and Grant was afraid that his slovenly appearance would insult Lee, but it did not. It was a friendly meeting, before getting down to business the two reminisced about the Mexican War.

Grant provided his vanquished foe very generous surrender terms:

“In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th inst., I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of N. Va. on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate. One copy to be given to an officer designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their commands. The arms, artillery and public property to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.”

When Lee left the building Federal troops began cheering but Grant ordered them to stop.

Grant felt a sense of melancholy and wrote: “I felt…sad and depressed, at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people has fought.” He later noted: “The Confederates were now our countrymen, and we did not want to exult over their downfall.”

In the hours before and after the signing of the surrender documents old friends and classmates, separated by four long years of war gathered on the porch or around the house. Grant and others were gracious to their now defeated friends and the bitterness of war began to melt away. Some Union officers offered money to help their Confederate friends get through the coming months. It was an emotional reunion, especially for the former West Point classmates gathered there.

“It had never been in their hearts to hate the classmates they were fighting. Their lives and affections for one another had been indelibly framed and inextricably intertwined in their academy days. No adversity, war, killing, or political estrangement could undo that. Now, meeting together when the guns were quiet, they yearned to know that they would never hear their thunder or be ordered to take up arms against one another again.”

Lee’s troops were starving and had few rations. Lee asked if Grant could provide rations, and Grant sent 25,000 rations to the starving Confederate army as it waited for the formal surrender. The gesture meant much to the defeated Confederate soldiers who had had little to eat ever since the retreat began.

The surrender itself was accomplished with a recognition that soldiers who have given the full measure of devotion can know when confronting a defeated enemy. Major General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, the heroic victor of Little Round Top was directed by Grant to receive the final surrender of the defeated Confederate infantry on the morning of April 12th.

It was a rainy and gloomy morning as the beaten Confederates marched to the surrender grounds. As the initial units under the command of John Gordon passed him, Chamberlain was moved with emotion he ordered his soldiers to salute the defeated enemy for whose cause he had no sympathy, Chamberlain honored the defeated Rebel army by bringing his division to present arms.

John Gordon, who was “riding with heavy spirit and downcast face,” looked up, surveyed the scene, wheeled about on his horse, and “with profound salutation returned the gesture by lowering his saber to the toe of his boot. The Georgian then ordered each following brigade to carry arms as they passed the third brigade, “honor answering honor.”

Gordon represents the beginning of the tragedy following the war. He was a slave owner from Georgia was not a professional soldier but rose through the ranks to be a highly effective commander. However, Gordon was a White Supremacist who retained his views until he died. He was a stalwart opponent of Reconstruction. In 1868 he told a meeting of blanks and whites in South Carolina: "If you are disposed to live in peace with the white people, they extend to you the hand of friendship" but "if you attempt to inaugurate a war of races, you will be exterminated. The Saxon race was never created by Almighty God to be ruled by the African."

Though never proven it is believed that Gordon was a leader in the Ku Klux Klan based on his statement to a Congressional committee that he was a member of a “secret peace police” which had the goal of keeping the peace. His biographer, Ralph Eckert believed that Gordon was a Klan leader, but that he may have only condoned violence when needed, noting: “Gordon may not have condoned the violence employed by Klan members, but he did not question or oppose it when he felt it was justified. In this sense, Gordon typified the upper levels of Southern society: he would do what had to be done to assure a white-controlled social order, but he hoped it could be accomplished without violence.” Gordon’s beliefs helped shape the views of generations of Southern political leaders that have led to the rollbacks of voting and civil rights for Blacks and others.

Chamberlain was not just a soldier before the war had been a Professor of Natural and Revealed Religions at Bowdoin College, and a student of theology before the war. He could not help to see the significance of the occasion. He understood that some people would criticize him for saluting the surrendered enemy. However, Chamberlain, unlike others, understood the value of reconciliation. Chamberlain was a staunch abolitionist and Unionist who had nearly died on more than one occasion fighting the defeated Confederate Army, and he understood that no true peace could transpire unless the enemies became reconciled to one another.

He noted that his chief reason for doing so:

“The momentous meaning of this occasion impressed me deeply. I resolved to mark it by some token of recognition, which could be no other than a salute of arms. Well aware of the responsibility assumed, and of the criticisms that would follow, as the sequel proved, nothing of that kind could move me in the least. The act could be defended, if needful, by the suggestion that such a salute was not to the cause for which the flag of the Confederacy stood, but to its going down before the flag of the Union. My main reason, however, was one for which I sought no authority nor asked forgiveness. Before us in proud humiliation stood the embodiment of manhood: men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve; standing before us now, thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking level into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond;—was not such manhood to be welcomed back into a Union so tested and assured? Instructions had been given; and when the head of each division column comes opposite our group, our bugle sounds the signal and instantly our whole line from right to left, regiment by regiment in succession, gives the soldier’s salutation, from the “order arms” to the old “carry”—the marching salute. Gordon at the head of the column, riding with heavy spirit and downcast face, catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up, and, taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command, gives word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position of the manual,—honor answering honor. On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer, nor word nor whisper of vain-glorying, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead!”

The surrender was the beginning of the end. Other Confederate forces continued to resist for several weeks, but with the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia led by the man that nearly all Southerners saw as the embodiment of their nation the war was effectively over.

Lee had fought hard and after the war was still under the charge of treason, but he understood the significance of defeat and the necessity of moving forward as one nation. In August 1865 Lee wrote to the trustees of Washington College of which he was now President:

“I think it is the duty of every citizen, in the present condition of the Country, to do all in his power to aid the restoration of peace and harmony… It is particularly incumbent upon those charged with the instruction of the young to set them an example of submission to authority.”

It is a lesson that all of us in our terribly divided land need to learn regardless of or political affiliation or ideology. After he had signed the surrender document, Lee learned that Grant’s Aide-de-Camp Colonel Ely Parker, was a full-blooded Seneca Indian. He stared at Parker’s dark features and said: “It is good to have one real American here.”

Parker, a man whose people had known the brutality of the white man, a man who was not considered a citizen and would never gain the right to vote, replied, “Sir, we are all Americans.” That afternoon Parker would receive a commission as a Brevet Brigadier General of Volunteers, making him the first Native American to hold that rank in the United States Army. He would later be made a Brigadier General in the Regular Army.

I don’t know what Lee thought of that. His reaction is not recorded and he never wrote about it after the war, but it might have been in some way led to Lee’s letter to the trustees of Washington College. I think with our land so divided, ands that is time again that we learn the lessons so evidenced in the actions and words of Ely Parker, Ulysses Grant, Robert E. Lee and Joshua Chamberlain, for we are all Americans.

Robert E. Lee admitted defeat, and though still at heart a racist, could still advocate ending the rebellion that he supported and reconciling with the government which he had committed high treason against. Ulysses S. Grant and Joshua Chamberlain embodied the men of the Union who had fought for the Union, Emancipation, and against the Rebellion that Lee supported to the bitter end at Appomattox.

But even more so we need to remember the words of the only man whose DNA and genealogy did not make him a European transplant. The man who Lee referred to as the only true American at Appomattox, General Ely Parker. Parker fought for a nation that did not acknowledge him as a citizen until long after he was dead, deserves the highest respect.

Sadly, I think that there is a portion of the American population who will not heed these words and will continue to agitate for policies and laws similar to those that led to the Civil War, and which those the could not reconcile defeat instituted again during the Post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras. For me such behavior and attitudes are incompressible, but they are all too real, and all too present in our divided nation, the most recent example being the expulsion of two African American members of the Tennesse House of Delegates.

But I still maintain hope that in spite of everything that divides us, in spite of the intolerance and hatred of some, that we can overcome. I think that the magnanimity of Grant in victory, the humility of Lee in defeat, the graciousness of Chamberlain in honoring the defeated foe, and the stark bluntness of Parker, the Native American, in reminding Lee, that “we are all Americans,” is something that is worth remembering, and yes, even emulating.