Titanic and Titan: Two Tragedies bound by Hubris

Stockton Rush, Bruce Ismay & the Consequences of Devaluing Safety for Profit

In 1912 the Bishop of Winchester said these words in a sermon marking the end of the R.M.S. Titanic: “Titanic, name and thing, will stand as a monument and warning to human presumption,” as well it should, as well as to Stockton Rush, and his submersible Titan. The parallels of hubris and reckless behavior between the people involved with Titanic and Titan are frightening.

I was fascinated with ships and submersibles at an early age. I couldn’t get enough of reading about deep sea diving and the early submersibles like the Trieste which first dove to Challenger Deep in the Marianas Trench, submarine rescues, like that of the crew of the USS Squalus, and naval salvage divers. Likewise, the story of Titanic captivated me since the time I watched the film A Night to Remember on television, followed by the book of the same name by Walter Lord which I read in 7th grade, and have pored through many times since, as well as every other book and article about the ship I have found.

The story of the Titanic has been told many times, and it should be a cautionary tale for those who in the name of profit and glory like Rush sought to disrupt an industry. Like so many involved in the loss of Titanic, Rush ignored and dismissed safety as an impediment to innovation. In June 2019 Rush told Smithsonian Magazine that the Passenger Vessel Safety Act of 1993 told Smithsonian Magazine was well intended, but was overly cautious by putting passenger safety over commercial innovation. He stated:

“There hasn’t been an injury in the commercial sub industry in over 35 years,” he told the magazine. “It’s obscenely safe, because they have all these regulations. But it also hasn’t innovated or grown - because they have all these regulations.”

Of course there is a reason for this, and it is because other operators of such vessels adhered to established practices to ensure that their vessels were safe and that in addition to years of design, testing, and validation of their designs, including subjecting themselves to external and independent checks. These Rush deliberately ignored. As far back as 2018 he rejected criticism from David Lochridge, then Oceansgate’s Director of Maritime Operations was concerned about the materials used in the hull and a lack of testing performed on the hull to measure its ability to withstand the intense pressures of deep waters. Lochridge was fired and sued by Oceansgate after submitting his report in 2018. In his counter suit, he said that testing and certification was insufficient and would “subject passengers to potential extreme danger in an experimental submersible.”

Rush told Arnie Weissmann, Editor in Chief of Travel Magazine in May that he got the carbon fiber for the Titan’s hull at a big discount because it was past its shelf-life for use in airplanes. But Rush reassured him it was safe. Think about that. If the carbon fiber was considered unfit to use on aircraft, why would anyone think that it would be safe to use on a vessel going where it would be subjected to rage massive water pressure of the depths.

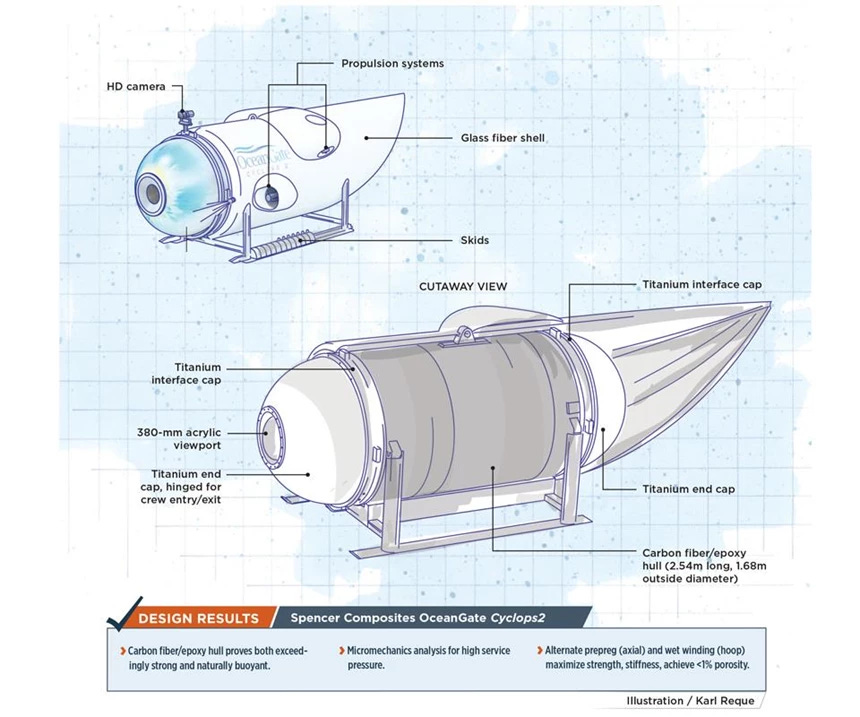

Rush designed a vessel that had five potential points where its hull could fail. There was the viewport, which was certified to just one third of the depth Titan was to operate. Second, there were the two titanium nose and stern end caps, the forward end cap hinged for entry and exit of the crew which were joined to the titanium interface caps that joined it to the carbon fiber passenger compartment, the largest hull component.

Jasper Graham-Jones, an associate professor of mechanical and marine engineering at the University of Plymouth in the United Kingdom noted that elongating the cabin space in a submersible increases pressure loads in the midsections, which increases fatigue and delamination loads. He explained that fatigue is like bending a wire back and forth until it breaks. Likewise, delamination, is like splitting wood down the grain, which is easier than chopping across the grain. The hull would have been subject to repeated stress over the course of its service which would put tiny cracks in the carbon fiber. Graham-Jones said, “This might be small and undetectable to start but would soon become critical and produce rapid and uncontrollable growth.”

Since Rush refused to submit the vessel to outside inspection, refused to have it certified, and even ruled against nondestructive testing using ultrasound or X-rays which are routinely used on undersea vessels, including nuclear submarines to check for flaws or damage that could endanger the vessel and its crew. Neal Couture, executive director of a professional organization called the American Society for Nondestructive Testing said, “Once this thing is going down and going under stress, it’ll affect those materials, it’ll affect those composites,… nondestructive testing is how you would then assess those structures and say, ‘OK, they’re still viable,’ or, ‘they’re still susceptible.’”

To all of these issues one has to add the minimal amount of testing, computer simulation, models, or real testing of the vessel before it entered service. Will Kohnen, the chairman of the Marine Technology Society sent a letter to Oceansgate in 2018 warning that its “current experimental approach ... could result in negative outcomes (from minor to catastrophic) that would have serious consequences for everyone in the industry.” His warning was also rejected.

A similar pattern of disregard for safety was found in Titanic. The Titanic’s Captain, Edward Smith, was blinded by his faith in shipbuilding technology and had said about the much smaller White Star Line, Adriatic, which he commanded previously, “I cannot imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. I cannot conceive of any vital disaster happening to this vessel. Modern ship building has gone beyond that.” One U.S. Senator said during the hearings about the sinking of Captain Smith, “Overconfidence seems to have dulled the faculties usually so alert.”

Walter Lord, who was probably the most prolific historian and author of the Titanic disaster used to talk of the “if onlys” that haunted him about the sinking of Titanic: “If only, so many if onlys. If only she had enough lifeboats. If only the watertight compartments had been higher. If only she had paid attention to the ice that night. If only the Californian did come…”

The word “if” probably the biggest two letter word that plagues human history, looms large in the tragedy of Titanic, and the tiny Titan. The great ship, which was the largest ship and one of the fastest ocean liners of her time was the victim of her owner and operator’s hubris as much as she was that of the iceberg which sank her. Titanic was heralded by Bruce Ismay, the Chairman and Managing Director of the White Star Line as unsinkable, a claim that was echoed in the press, as well as many the leading maritime “experts” and ship captains of the time.

Her builders had no such illusions and protested the claims. Thomas Andrews the Managing Director of Harland and Wolff Shipyards where she was built commented, “The press is calling these ships unsinkable and Ismay’s leadin’ the chorus. It’s just not true.”

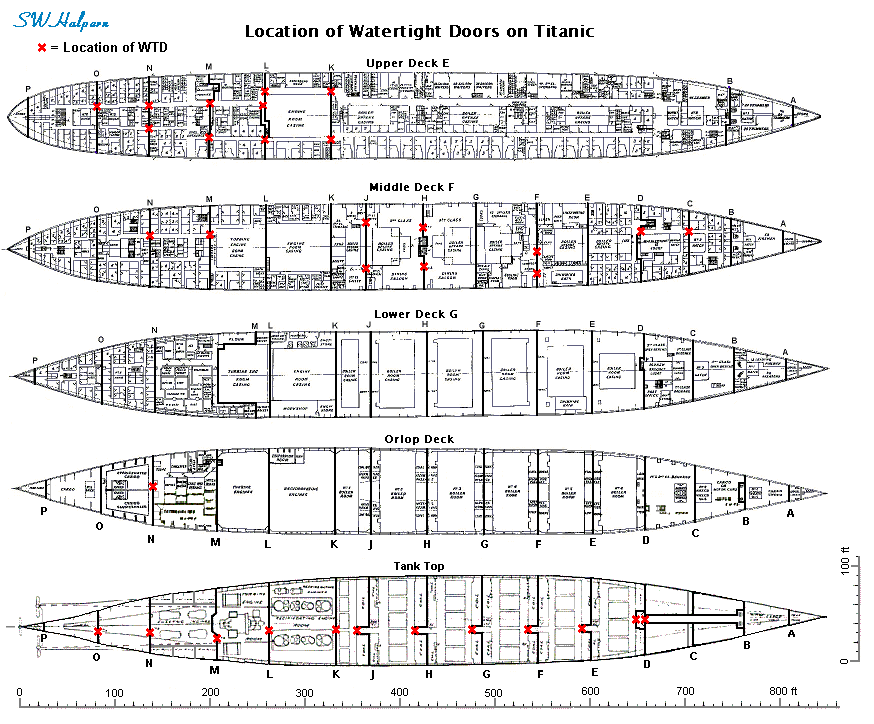

Though Titanic was designed with watertight compartments, a double bottom and equipped with wireless, she was not unsinkable as touted by her owners, and experts who never inspected her. However, those innovations were nowhere as advanced as advertised. Lord wrote in his book The Night Lives On: the Untold Stories and Secrets of the Unsinkable Ship - Titanic:

“How close to “unsinkable” really was the Titanic? Did she embody the latest engineering techniques? Was she as staunch as man could make her? Did she at least represent what we have now come to call “the state of the art”? The answer is “No.” Far from being a triumph of safe construction, or the best that could be done with the technology available, the Titanic was the product of a trend the other way, a trend that for 50 years had seen one safety feature after another sacrificed for competitive reasons.”

The achievable safety standards had been set by the Great Eastern in 1858. She was the largest ship of her day, a mammoth liner of 19,000 tons and nearly 700 feet in length. Like Titanic she had 16 watertight compartments, but hers extended to her main deck which was also watertight. There were no watertight doors as there are in current ships which meant the crew and passengers had to go to the main deck and back down to reach another compartment. She also had two longitudinal bulkheads that ran the whole length of her boiler and engine rooms, something not provided for on Titanic. “The honeycomb of walls and decks gave her a total of some 40-50 separate watertight compartments.” Evil more importantly, she was the first ship to have a double hull. She was two ships in one. The outer hull was connected to an inner hull by braces that spanned the 2 foot ten inches that separated them.

Great Eastern was a commercial failure because she was underpowered and unwieldy, but she was safe. Her safety was demonstrated on August 27th, 1862 when she hit an uncharted rock off Montauk Point, Long Island. She was carrying over 800 passengers bound for New York. The rock created a gash in her outer skin 83 feet long and 9 feet wide, but her inner hull was not pierced, and though listing she made it into port on her own power.

Maritime engineers, especially those that designed warships developed watertight doors which allowed access between compartments later in the 19rh Century. However, watertight bulkheads and compartments were used by the Chinese by the 12th Century and Marco Polo wrote of their ship design while embarked aboard ships provided by Kublai Khan in 1292. Benjamin Franklin wrote of them in a letter to Alphonsus Le Roy in August 1785:

“While on the topic of sinking of ships, one cannot help recollecting the well-known practice of the Chinese, to divide the hold of a great ship into a number of separate chambers by partitions, tight caulked, so that if a leak should spring in one of them the others are not affected by it…We have not initiated this practice.”

Walter Lord wrote of how quickly the concerns for safety were discarded after Great Eastern:

But the engineers did not have the last word for very long. The speed and reliability of the new steamships meant a great surge in trans-Atlantic travel, with profits further fattened by the growing emigrant trade and generous mail contracts. The stakes were high, and by 1873 eleven major lines were fighting for their share. Entrepreneurs and promoters moved in, and the perfect ship was no longer the vessel that best expressed the art of the shipbuilder. It was the ship that made the most money.

Titanic’s watertight compartments did not extent far enough up the hull to prevent water from going over them. Unlike Great Eastern whose watertight bulkheads extended 30 feet above the waterline, the Titanic’s only rose 10 feet above the waterline at their highest point. Likewise, it was never imagined that so many watertight compartments could be compromised. Though she was designed to stay afloat with four compartments flooded, the worst imagined damage was from a collision with another ship that breached two compartments.

As far as lifeboats, the great ship carried far too few. Thomas Andrews wanted 64 lifeboats, but was forced to reduce the number to 32. When Titanic sailed she only carried 20, of which 4 were collapsible boats smaller than smaller lifeboats. Bruce Ismay, the Director of the White Stare Line, justified his decision to reduce the number of lifeboats himself under antiquated regulations (which were written for ships of 10,000 tons) which allowed just 16 boats. He told Andrews:

“Control your Irish passions, Thomas. Your uncle here tells me you proposed 64 lifeboats and he had to pull your arm to get you down to 32. Now, I will remind you just as I reminded him these are my ships. And, according to our contract, I have final say on the design. I’ll not have so many little boats, as you call them, cluttering up my decks and putting fear into my passengers.”

The period of builders trials and shakedown cruises intended to work out any issues with the ship and for the crew to become familiarized with it was unsatisfactory for a vessel so large and fast. Normally, new ships are put through months of trials to identify and correct any deficiencies discovered after launch, and to familiarize the crew and its officers with its design, features, and how she sailed. Such trials include full speed runs, emergency turns at speed, and emergency stops at top speed.

Titanic’s trials were not helpful. The ship never went into the open ocean but lasted less than a day in Belfast Lough. In them she never went at full speed. Lord wrote that “she spent several hours making twists and turns, then four more hours on a straight run down the Lough and back. She made only one test to see how fast she could stop. At 18 knots, with both engines in reverse, the time was 3 minutes, 15 seconds; the distance, 3,000 feet. She would have nothing like that 12 days later.”

After the disaster the tragedy was investigated by the United States Senate, as well as the British Board of Trade. However, the inquiry of the latter was condemned by the White Star Line’s Archivist, Paul Louden-Brown. He noted: “I think the enquiry is a complete whitewash. You have the [British] Board of Trade in effect enquiring into a disaster that’s largely of its own making.”

Bruce Ismay and Stockton Rush are symbolic of men guided only by their quest for riches and glory who revel in their power and scorn wise counsel or regulation, government or otherwise. They often believe that rules don’t apply to them. It is a cautionary tale for us today as corporations, lobbyists, and politicians seek to dismantle sensible and reasonable safety and environmental regulations for the sake of their unmitigated profit.

But the warning goes far beyond that, it applies to any of us who adopt the mindset, “this cannot happen to us.” After all, there are times when we all end up as victims of our own hubris, such is the human condition.