“We had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages” Hiroshima and After

I watched the film Oppenheimer last week. I found it well worth watching and probably another time will it is still in theaters. Critics have made valid points on how it could be better, a deeper presentation of the women in Oppenheimer’s life, the effects of the bomb tests on the Native Americans of New Mexico and other residents of the area, and the inclusion of what happened at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Despite not being included I do not think that the message of the film about the deadly effects dropping the atomic bombs on Japan, the moral and ethical effects of the atomic and later hydrogen bombs on the world in the decades since.

Viktor Frankl wrote: “Since Auschwitz we know what man is capable of. And since Hiroshima we know what is at stake.”

Those are chilling words. With only a few of the weapons available to the nuclear powers of today could kill more people in minutes than all the Jews killed by the Nazis killed in the Holocaust.

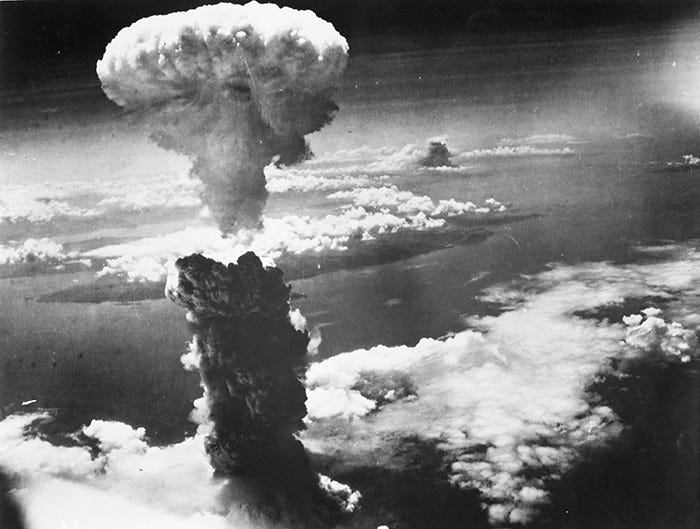

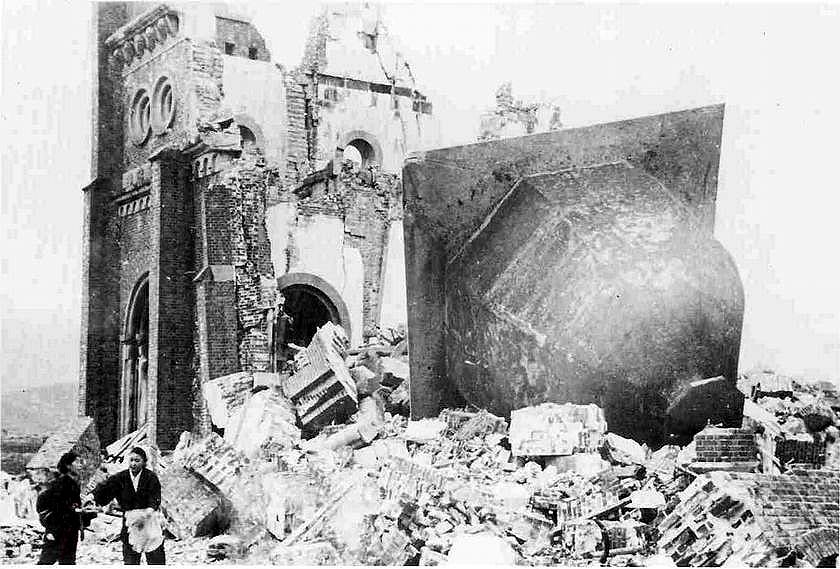

Today marks the anniversary of the use of the bomb named Little Boy on Hiroshima. The approximately 15 kiloton bomb dropped on Hiroshima killed an estimated 66,000 people and injured another 69,000. Later estimates put the number of fatalities at 80,000 and 151,000 injured. Those do not include the large number of people who died of radiation caused cancers, in later years. August 9th is the anniversary of the second and hopefully last nuclear weapon used in war, the bomb called the Fat Man which was dropped on the Japanese city of Nagasaki. The United States initially put the casualties of the Nagasaki bomb at 39,000 killed and 25,000 injured. Official Japanese figures issued in the late 1990s state the total number of people killed in the Nagasaki attack exceeded 100,000.

Kurt Vonnegut who survived the allied terror bombing of Dresden as a POW in 1945 wrote:

“The most racist, nastiest act by America, after human slavery, was the bombing of Nagasaki. Not of Hiroshima, which might have had some military significance. But Nagasaki was purely blowing away yellow men, women, and children. I’m glad I’m not a scientist because I’d feel so guilty now.”

However, there were those in the military at the time who opposed the decision to drop either bomb on Japan. They included General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Admiral Chester Nimitz.

Both the cities were nearly untouched military targets at time since most major Japanese cities and had already been incinerated in low level fire bombing raids. In those raids hundreds of B-29s using thousands small incendiary bombs destroyed Japanese cities and incinerated hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians. While these raids were designed to destroy industrial and military targets, which were often intermixed in civilian neighborhoods, they were also designed to kill Japanese civilian workers in massive fire storms, or render them homeless in order to cripple Japanese war production.

The first atomic bombs were experimental. While the Trinity test proved the bombs would work, the Japanese cities gave the military a chance to try them out on two very different targets. Hiroshima was located in a flat area which allowed the blast of the bomb to damage a larger area than Nagasaki, where the target area was surrounded by hills the limited the effect to a smaller area. Some of the scientists who build the bombs, as well as senior military officers suggested either warning the targeted cities, or conducting a demonstration in Tokyo Bay, but their advice was rejected.

To President Truman, Secretary of War Stimson and some military leaders, especially General Curtis LeMay, they served a strategic purpose. However, many other reasonable American military Commanders including Admiral William Leahy, General Dwight Eisenhower, Admiral Chester Nimitz, and General Hap Arnold, disagreed believing Japan was close to surrender. Likewise, since Japan had no means of attacking the United States or even major military bases in the Pacific with anything close to the power of atomic bomb, all sense of the principle of proportionality was lost.

The decision to drop these weapons, forever changed the consequences of waging war, especially total war. It was a decision that still haunts humanity, and one which policy makers and military strategists wrestle with in an age where nine nations have deployable nuclear weapons and other nations are developing or trying to obtain them. At a time when a major nuclear power is waging war against its neighbor, and some of its leaders issue threats of using them, one has to be concerned. John Hersey, the first American reporter with free access to visit Hiroshima and write about Hiroshima would later write words that the leaders of nations possessing nuclear weapons and their military chiefs must truly ponder before deciding to go to war, especially if they plan to wage a total war:

“The crux of the matter is whether total war in its present form is justifiable, even when it serves a just purpose. Does it not have material and spiritual evil as its consequences which far exceed whatever good might result? When will our moralists give us an answer to this question?”

It is also the subject that is wrestled with by students of major military staff colleges and universities. I know, I taught the ethics elective at the Joint Forces Staff College. In each of our classes at least one brave officer did a presentation detailing the ethical issues involved the decision and the implications today. For those not familiar with the military the truth is that most officers are quite circumspect and much more grown up about the subject than the average citizen, politician, or media host. But then there are probably some in the military who would be like Colonel Paul Tibbets who flew the B-29 bomber Enola Gay which dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima. In a 1989 interview Tibbets said these words:

“I made up my mind then that the morality of dropping that bomb was not my business. I was instructed to perform a military mission to drop the bomb. That was the thing that I was going to do the best of my ability. Morality, there is no such thing in warfare. I don’t care whether you are dropping atom bombs, or 100-pound bombs, or shooting a rifle. You have got to leave the moral issue out of it.”

War is terrible, but in every war, every commander or soldier is called to make moral decisions. We tried Nazi commanders for war crimes for violating the laws of war which centuries of philosophers, ethicists, and military leaders sought to hone in order to minimize the chances of war, and to limit its devastation.

Tibbets, like Truman justified his position based on his view of the bestiality of the crimes committed by the Japanese during the war. It was quite a common point of view. Both views are troubling considering the power of the weapons that were used, and the fact that the Japanese had no way to strike the United States. The reasoning of Truman and Tibbets sounds similar to German military officers and political officials on trial at Nuremberg between 1945 and 1948.

The atomic bomb was a wonder weapon that promised to end the war with a minimum of American casualties, as Truman said in 1952:

“I gave careful thought to what my advisors had counseled. I wanted to weigh all the possibilities and implications… General Marshall said in Potsdam that if the bomb worked we would save a quarter of a million American lives and probably save millions of Japanese… I did not like the weapon… but I had no qualms if in the long run millions of lives could be saved.”

But there were other considerations. Truman was fixated on revenge for Pearl Harbor and to intimidate the Soviet Union since the United States was the sole atomic power until 1949. But Truman’s decision on his, and many Americans view that the Japanese were barbaric animals and subhuman. There was a certain element of racism in his view of Asians which was little different than the Nazis views of they referred to as sub-human.

This racial prejudice was common in the mid-twentieth century, and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor only increased the blood lust, not that the Japanese also didn’t consider Europeans or Americans as equal to them, because they too, were a Master Race. This resulted in the war in the Pacific being much more brutal and inhuman than the one the Americans and British fought against the Nazis.

Truman responded to a telegram from the Reverend Samuel McCrea Cavert, the General Secretary of the Federal Council of The Churches of Christ in America, the predecessor of the National Council of Churches. Reverend Cavert was a Presbyterian minister. Cavert’s telegram stated:

“Many Christians deeply disturbed over use of atomic bombs against Japanese cities because of their necessarily indiscriminate destructive efforts and because their use sets extremely dangerous precedent for future of mankind. Bishop Oxnam, President of the Council, and John Foster Dules, Chairman of its Commission on a just and durable peace are preparing statement for probable release tomorrow urging that atomic bombs be regarded as trust for humanity and that Japanese nation be given genuine opportunity and time to verify facts about new bomb and to accept surrender terms. Respectfully urge that ample opportunity be given Japan to reconsider ultimatum before any further devastation by atomic bomb is visited upon her people.”

Truman’s response to the telegram revealed the darker side of his decision to use the bomb.

My dear Mr. Cavert:

I appreciated very much your telegram of August ninth.

Nobody is more disturbed over the use of Atomic bombs than I am but I was greatly disturbed over the unwarranted attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor and their murder of our prisoners of war. The only language they seem to understand is the one we have been using to bombard them.

When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him as a beast. It is most regrettable but nevertheless true.

The President’s senior military advisors were certainly of a different point of view about the use of the weapons. Admiral William Leahy who served as Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief and was the senior Naval Officer in service disagreed and told Stimson of his misgivings about using the atomic bomb at this particular point in the war. In his memoirs which were released in 1949 he wrote:

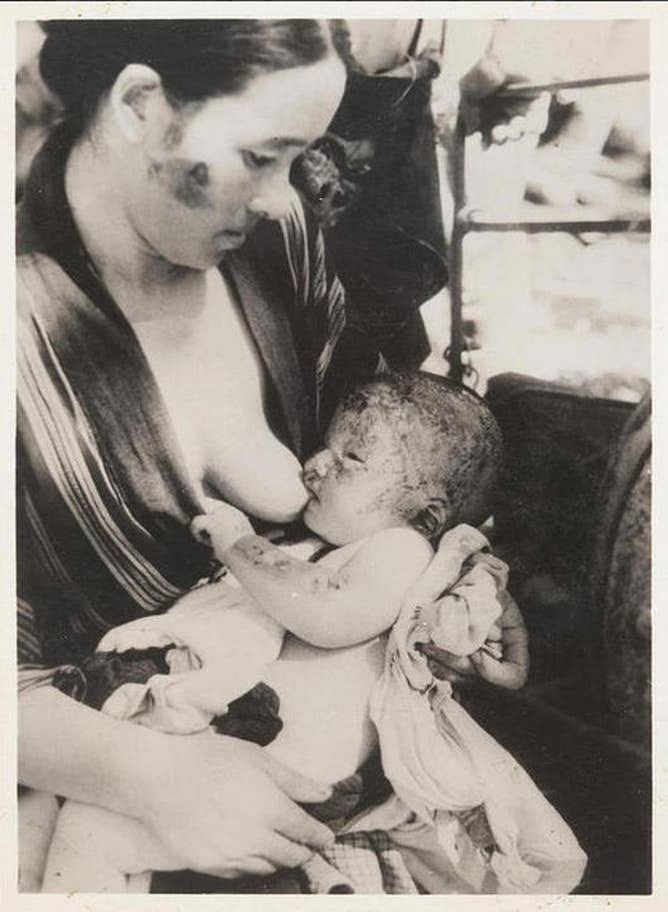

“It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons… My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make wars in that fashion, and that wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.”

General Dwight D. Eisenhower disagreed with the use of the atomic bomb and recorded his interaction with Stimson:

“In 1945 Secretary of War Stimson, visiting my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act. During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives.” He also wrote later words similar to Leahy:

“I was against it on two counts. First, the Japanese were ready to surrender, and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing. Second, I hated to see our country be the first to use such a weapon.”

Stimson did not agree with the Eisenhower, he would later recall words that echoed those of Truman in 1952, not his words to Revered Cavert immediately after the event.

“My chief purpose was to end the war in victory with the least possible cost in the lives of the men in the armies which I had helped to raise. In the light of the alternatives which, on a fair estimate, were open to us I believe that no man, in our position and subject to our responsibilities, holding in his hands a weapon of such possibilities for accomplishing this purpose and saving those lives, could have failed to use it and afterwards looked his countrymen in the face.”

Admiral William Leahy wrote in his memoirs:

“Once it had been tested, President Truman faced the decision as to whether to use it. He did not like the idea, but he was persuaded that it would shorten the war against Japan and save American lives. It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons… My own feeling was that in being the first to use it, we had adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages. I was not taught to make wars in that fashion, and that wars cannot be won by destroying women and children.”

General Hap Arnold, the Commander of the Army Air Forces noted: “It always appeared to us that, atomic bomb or no atomic bomb, the Japanese were already on the verge of collapse.”

Those who questioned the decision would be vindicated by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey study published in 1946. That study laid out the facts in stark terms:

“Certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.”

Later, Dr. J. Samuel Walker, the Chief Historian of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission wrote:

“Careful scholarly treatment of the records and manuscripts opened over the past few years has greatly enhanced our understanding of why Truman administration used atomic weapons against Japan. Experts continue to disagree on some issues, but critical questions have been answered. The consensus among scholars is the that the bomb was not needed to avoid an invasion of Japan. It is clear that alternatives to the bomb existed and that Truman and his advisers knew it.”

Thus the moral question remains and perhaps is best answered by the words of Dr. Leó Szilárd who first proposed building atomic weapons. In 1960 he noted to U.S. News and World Reports:

Suppose Germany had developed two bombs before we had any bombs. And suppose Germany had dropped one bomb, say, on Rochester and the other on Buffalo, and then having run out of bombs she would have lost the war. Can anyone doubt that we would then have defined the dropping of atomic bombs on cities as a war crime, and that we would have sentenced the Germans who were guilty of this crime to death at Nuremberg and hanged them?

But, again, don’t misunderstand me. The only conclusion we can draw is that governments acting in a crisis are guided by questions of expediency, and moral considerations are given very little weight, and that America is no different from any other nation in this respect.

I think now, three quarters of a century later we need to ponder that question before it can happen again. India and Pakistan are moving closer to nuclear war, Russia, China, North Korea, and yes even the United States are modernizing weapons and delivery systems. Admiral Leahy, General Eisenhower, and Dr. Szilard turned out to be right. As did General Omar Bradley who said:

“Ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants. We know more about war than we know about peace, more about killing than we know about living. If we continue to develop our technology without wisdom or prudence, our servant may prove to be our executioner.”

Eisenhower, Leahy, Bradley, and Szilard were correct. The weapons have grown more deadly, the delivery systems, more accurate with greater range, speed, and maneuverability, and even their miniaturization, make their use more likely than not. If they are used it will be the beginning of the end.

Robert Oppenheimer told Truman that he “had blood on his hands” after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but while he later opposed building the Hydrogen Bomb, but never backed off his Atomic weapons, and never indicated any other remorse for their use. As brilliant and complex as he was, Oppenheimer seemed to lose his ethics when the invention was his, and not Edward Teller’s.

Albert Einstein’s words which he penned after the bombing should serve as a warning to Americans for all time, while pointedly taking on America’s own racism toward American Blacks:

“America is a democracy and has no Hitler, but I am afraid for her future; there are hard times ahead for the American people, troubles will be coming from within and without. America cannot smile away their Negro problem nor Hiroshima and Nagasaki. There are cosmic laws.”

Nuclear weapons systems far exceed in number, and power than those of the 1940s and 1950s, with far more capable delivery systems. With the developments in Artificial Intelligence and hypersonic missiles, we may lose the chance of preventing nuclear war.

Your topics are well-chosen and decidedly worth the effort (on yours as a thoughtful chaplain and on the readers'). Thanks you for openly sharing the process. Not everything fits neatly into a package, and your explodes with incongruities. This is not a criticism. In fact, you let the quotes speak for themselves. Einstein refers to "the Negro problem" and I immediately considered "the Jewish problem", and the "final solution". It always troubled me that Germany was so far advanced in so many intellectual and artistic endeavors and somehow managed to "industrialize" genocide.

My real fears are not with the military industrial complex, which are of immediate concern, but of the "medical" (or scientific) industrial complex, which holds the possibility of great good, and even greater harm! - You can quote me. BA

Not sure this statement you made has any merit: " With only a few of the weapons available to the nuclear powers of today could kill more people in minutes than all the Jews killed by the Nazis killed in the Holocaust."

I am still making my way through the rest of your post, but I want to bring this to your attention.

It's a hypothetical which cannot be proven, nor does it enhance your position. One death is too many, so it's not necessary to quantify which is more heinous.