“With Silent Tongue, the Clenched Teeth, the Steady Eye, the Well Poised Bayonet, They have Helped Mankind on to this Great Consummation”: Black Soldiers and Juneteenth

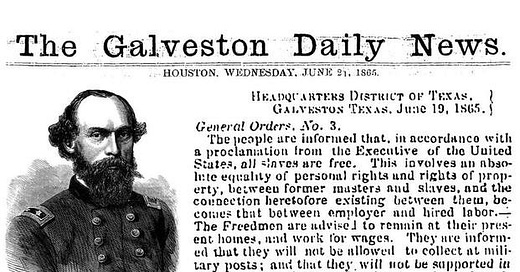

One hundred and fifty-eight years ago U.S. Army Soldiers led by Major General Gordon Granger the commander of the newly restored Military District of Texas landed in Galveston, Texas. General Granger had 2,000 troops with him and rightly is given credit for issuing General Orders #3 which immediately required slavery’s end, the emancipation of all slaves, and ordered the absolute equality of the personal and property rights of people. This is the rightful origin of Juneteenth, a truly unique American holiday that recognizes the frightful institution the preceded the Declaration by over 250 years and lingered as a poison in our nation until the ratification of the XIIIth Amendment following the Civil War.

General Granger’s oder stated the terms of the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1st, 1863. But this is not the whole story, Juneteenth was the culmination of the courage, bravery, and skill of every Union soldier and sailor, including over 200,000 African Americans.

However, Granger’s force was not the only body of Federal Troops that had arrived in Texas or was in Galveston on that first Juneteenth. Four regiments of Major General Godfrey Weitzel’s all African American XXV Corps which had landed at Brownsville in early May after leading the liberation of Richmond on April 3rd, 1865. The four regiments, the 28th Indiana, 29th Illinois, the 26th and 31st U.S. Colored Troops Regiments recruited in New York, had landed in Galveston the day prior to Granger’s force. These were combat tested units. The 28th Indiana lost over half its numbers at the Battle of the Crater during the siege of Petersburg. The 29th Illinois also fought at the Battle of the Crater, the siege of Petersburg and at Appomattox. The 26th U.S.C.T. fought battles throughout South Carolina, and the 31st U.S.C.T. participated in the Wilderness and Overland Campaigns, the siege of Petersburg and the liberation of Richmond, and Appomattox. Their presence certainly aided Granger’s efforts, although their commanders, not being the head of the new administration would not have had the power to issue an order for the whole of Texas, as Granger did.

Following the Emancipation Proclamation, Frederick Douglass told Free Blacks in Philadelphia who were questioning the value of fighting for a government which for most of its existence did all that it could to harm them. Douglass would have none of it:

“Now, what is the attitude of the Washington government towards the colored race? What reasons have we to desire its triumph in the present contest? Mind, I do not ask what was its attitude towards us before the war. . . . I do not ask you about the dead past. I bring you to the living present . . .

Do not flatter yourselves, my friends, that you are more important to the Government than the Government to you. You stand but as the plank to the ship. This rebellion can be put down without your help. Slavery can be abolished by white men: but liberty so won for the black man, while it may leave him an object of pity, can never make him an object of respect. . . . Young men of Philadelphia you are without excuse. The hour has arrived, and your place is in the Union army. Remember that the musket—the United States musket with its bayonet of steel—is better than all the mere parchment guarantees of liberty. In your hands that musket means liberty.”

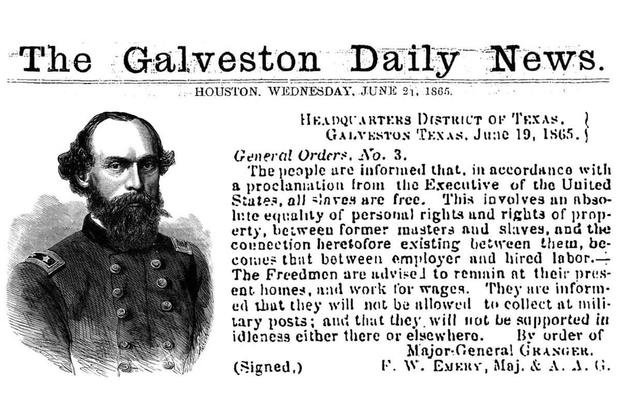

Soldiers of E Company 4th USCT above and 2nd USCT Artillery below

African American soldiers helped turn the tide of the war in favor of the Union. While many people only know of them through the film Glory about the heroism of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry at Fort Wagner. However, over 200,000 Blacks served in the Union Army in U.S.C.T. units, after the Emancipation Proclamation, and thousands more who served in the United States Navy which unlike the Army was not segregated, and in which Blacks could serve in every enlisted rate and work, eat, and berth alongside their White shipmates. They could not be officers, but in every respect they enjoyed the same pay and privileges as White Sailors. That ended in 1915 when Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels restricted Blacks to being Mess Stewards during the Wilson Administration’s systematic attack on Blacks serving in the Federal Government.

These Black soldiers and sailors were key to the Union victory. Some were Freedmen who volunteered as soon as they were allowed, others were either escaped slaves or newly freed slaves from areas in the South controlled by Union forces. By the end of the war the U.S.C.T. fielded seven regiments of cavalry, more than a dozen artillery regiments, and well over one hundred infantry regiments. On the first of January 1865 the U.S.C.T. fielded more soldiers than the entire Confederate Army present for duty. Many of these units fought in some of the bloodiest battles of the war and distinguished themselves in battles against superior numbers of Rebel troops, including at the Battle of Milliken’s Bend where two newly recruited and inexperienced regiments were attacked by a Texas Division which was attempting to relieve Vicksburg. Though untrained and ill-armed, they beat back the Texans:

“Most of the black troops nevertheless fought desperately. With the aid of two gunboats they finally drove off the enemy. For raw troops, wrote Grant, the freedmen “behaved well.” Assistant Secretary of War Dana, still with Grant’s army, spoke with more enthusiasm. “The bravery of the blacks,” he declared, “completely revolutionized the sentiment in the army with regard to the employment of negro troops. I heard prominent officers who had formerly in private had sneered at the idea of negroes fighting express after that as heartily in favor of it.”

The Battle of Milliken’s Bend above and the Battle of Port Hudson below

The 54th Massachusetts at Fort Wagner

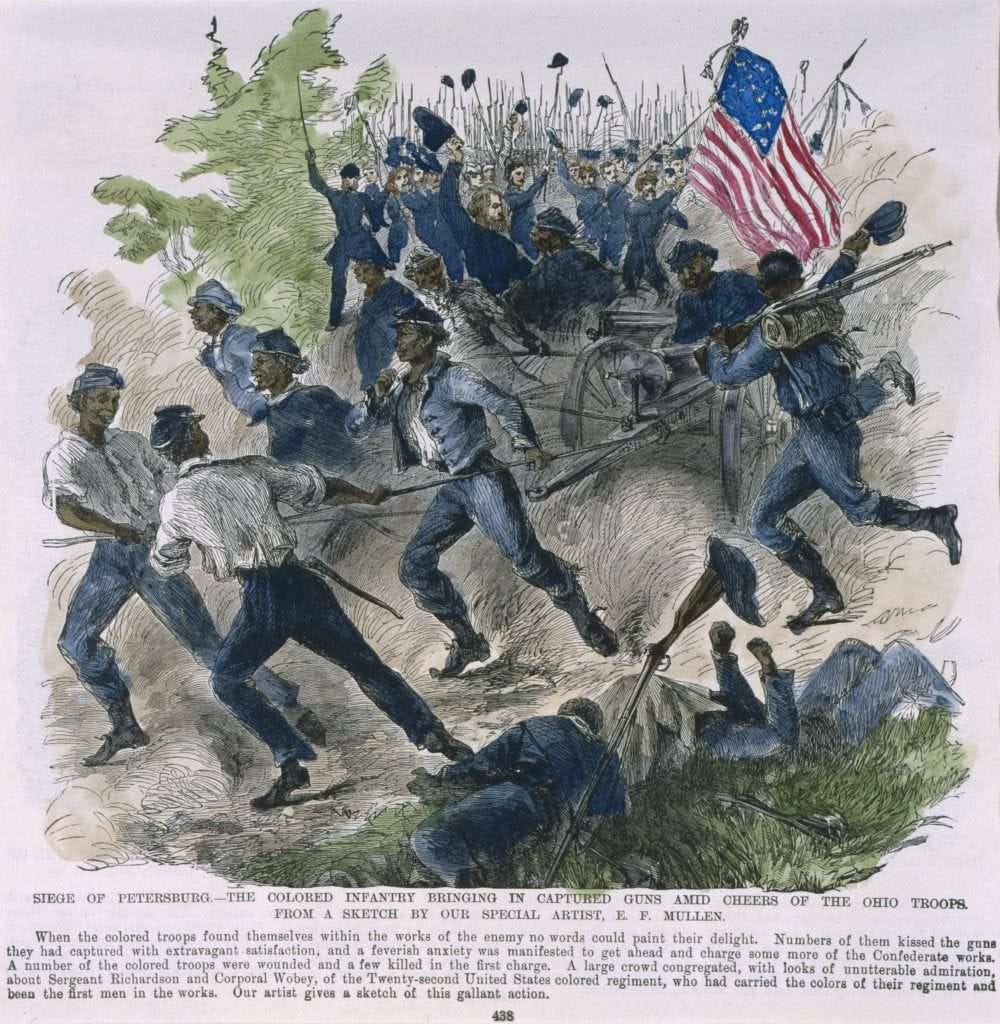

The 54th Massachusetts assaulting Fort Wagner above, and U.S.C.T. Troops at Petersburg dragging a captured cannon back to Union lines, below.

Southerners were shocked by the battle. One woman commented, “It is hard to believe that Southern soldiers—and Texans at that—have been whipped by a mongrel crew of white and black Yankees. . . . There must be some mistake.” As a Louisiana woman confided to her diary, “It is terrible to think of such a battle as this, white men and freemen fighting with their slaves, and to be killed by such a hand, the very soul revolts from it, O, may this be the last.”

When the Union began to form African American units the Confederate government of Jefferson Davis issued what later would be called at Nuremberg, criminal orders.

Confederate actions against Black Union soldiers would be considered war crimes today:

In “the autumn of 1862 General Beauregard referred the question of a captured black soldier to Davis’s latest Secretary of War, James A. Seddon the later replied ‘. . . my decision is that the negro is to be executed as an example.’”62 In November 1862 Davis approved of summary executions of Black prisoners in South Carolina. A month later “Davis issued a general order requiring all former slaves and their officers captured in arms to be delivered up to state officials for trial.” Davis said, “The army would consider black soldiers as ‘slaves captured in arms,’ and therefore subject to execution.”64 Confederate soldiers frequently massacred captured Black soldiers. Lincoln responded to Confederate crimes by threatening reprisals against Confederate soldiers if Black soldiers suffered harm. It “was largely the threat of Union reprisals that thereafter gave African-American soldiers a modicum of humane treatment.”65 Even so, they and their white officers were always in more danger than white soldiers at the hands of Confederates,

Black soldiers and their white officers often received no quarter when captured. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, who commanded Confederate forces west of the Mississippi, instructed Gen. Richard Taylor to execute Black soldiers and their white officers: “I hope . . . that your subordinates who may have been in command of capturing parties may have recognized the propriety of giving no quarter to armed negroes and their officers. In this way we may be relieved from a disagreeable dilemma.”

Confederates targeted white officers commanding Blacks: “Any commissioned officer employed in the drilling, organizing or instructing slaves with their view to armed service in this war . . . as outlaws” would be “held in close confinement for execution as a felon.” Following the attack of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment on Fort Wagner, Confederates gave no quarter. One Georgia soldier “reported with satisfaction that the prisoners were ‘literally shot down while on their knees begging for quarter and mercy.’”

On April 12, 1864, Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s raiders massacred at least 231 mostly Black Union soldiers at Fort Pillow. While Forrest did not order the massacre, he lost control of his troops, and “the best evidence indicates that the ‘massacre’ . . . was a genuine massacre.”

When Black soldiers were victorious, they often treated captured Confederates mercifully. Colonel Brisbin wrote following Battle of Saltville, “Such of the Colored Soldiers who fell into the hands of the Enemy during the battle were murdered. The Negroes did not retaliate but treated the Rebel wounded with great kindness, carrying them water in their canteens and doing all they could to alleviate the sufferings of those whom the fortunes of war had placed in their hands.”

Juneteenth was not solely the result of the great sacrifices of White Union soldiers on so many battlefields, but by the sacrifice and courage of African American Soldiers. These men, as well as Guerilla leaders like Harriet Tubman operating behind Confederate lines helped pave the way to victory over the Confederacy and the celebrating the holiday of Juneteenth.

Black soldiers paved the way for Lincoln, Radical Republicans in Congress, and Ulysses Grant to secure for the equality, citizenship, and suffrage of all Blacks. If they could fight and die for the country, how could they be denied the right to vote, to be elected to office, to serve on juries, or to go to public schools? During the summer of 1864, under political pressure to end the war, Lincoln reacted angrily to Copperheads and wavering Republicans on the issue of emancipation, as James McPherson wrote:

“But no human power can subdue this rebellion without using the Emancipation lever as I have done.” Lincoln pointed out to War Democrats that some 130,000 black soldiers were fighting for the Union: “If they stake their lives for us they must be prompted by the strongest motive—even the promise of freedom. And the promise being made, must be kept.” To abandon emancipation “would ruin the Union cause itself. All recruiting of colored men would instantly cease, and all colored men in service would instantly desert us. And rightfully too. Why should they give their lives for us, with full notice of our purpose to betray them? . . . Abandon all the posts now possessed by black men, surrender these advantages to the enemy, & we would be compelled to abandon the war in 3 weeks.” Besides there was the moral question: “There have been men who proposed to me to return to slavery the black warriors of Port Hudson & Ousttee [a battle in which Black soldiers fought] I should be damned in time & in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends & enemies, come what will.”

The importance of Black soldiers to the war effort cannot be minimized, for without them the conflict could have dragged on much longer, or ended in stalemate, which would have meant Confederate victory. Lincoln wrote in 1864 about the importance of the Black contribution:

Any different policy in regard to the colored man, deprives us of his help, and this is more than we can bear. We can not spare the hundred and forty or hundred and fifty thousand now serving us as soldiers, seamen, and laborers. This is not a question of sentiment or taste, but one of physical force which may be measured and estimated as horse-power and Steam-power are measured and estimated. Keep it and you save the Union. Throw it away, and the Union goes with it.

Yet Blacks faced discrimination during and after the war, sometimes even from white men that they served alongside, but most often from those who did not support the war or emancipation. Lincoln took note of this: “There will there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, the clenched teeth, the steady eye, the well poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it.”

We must take renewed courage and not just remember Juneteenth as a holiday, but continue to fight for the freedoms gained at such a high cost, freedoms that too many whites have fought to curtail or end, from the rollback of Reconstruction and Jim Crow to the present. We must take heart and courage from the story of two wounded U.S.C.T. Soldiers conversing in a hospital. One of them looked at the stump of an arm he had once had and remarked: ‘Oh I should like to have it, but I don’t begrudge it.’ His ward mate, minus a leg, replied: ‘Well, ’twas [lost] in a glorious cause, and if I’d lost my life I should have been satisfied. I knew what I was fighting for.’”

Juneteenth needs to be a rallying point where we as Americans recommit to the ideals of the Declaration that “we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among them, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”; and Lincoln’s words at Gettysburg which can be quite appropriately extended to all the other fallen in the war, including the African American soldiers whose sacrifices for liberties that they often did not enjoy benefited every American and those oppressed by Nazis, Communists, and other tyrants around the world.

“But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Let us celebrate Juneteenth from now until the consummation of history, and let us not forget those brave men of the white Army units and the U.S.C.T.

Dear Reader,

Much of this article is excerpted from my book Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory: Religion and the Politics of Race in the Civil War Era and Beyond, (Potomac Books, an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, Oct. 2022). The book is available at many online and brick and mortar retailers. You may also get an inscribed copy by becoming or upgrading your subscription to a Founding Member. Thank you so much for taking time to read Dedicated to the Proposition that All are Created Equal and your present subscription, be it paid or free. There is so much worth reading that I do not take the time that you spend reading my work for granted. Peace.

Steve