Remembering the 11th Hour of the 11th Day of the 11th Month: Armistice, Remembrance, Veterans Day, and Tipperary

In Flanders fields the poppies blow, Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky, The larks, still bravely singing, fly Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago, We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die,

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow, In Flanders fields.

Lieutenant Colonel John McRae, Canadian Army, May 3rd, 1915

I paused quietly at Eleven AM this morning to remember and honor the men of World War One, the Great War as it was once known. Twenty years after its end, Congress made November 11th a national holiday, Armistice Day. In 1954, President Eisenhower renamed it Veterans Day. In the United Kingdom and many Commonwealth Nations it is known as Remembrance Day. Traditionally a Red Poppy is worn, and Poppy Wreaths are laid at monuments and military cemeteries, to signify the poppies that grew on the cratered landscapes of the World War One battlefields in Western Europe.

The war cost the lives of some 9.7 million soldiers, and 10 million civilians, with another 20 million wounded and devastated vast amounts of Belgium and France. Unexploded ordnance still kills people who accidentally encounter it or Explosive Ordnance Disposal personnel who attempt to neutralize them.

In the aftermath of the war countless wounded soldiers suffered in mind and body, often without much aid from government or civilian agencies. Rudyard Kipling wrote his poem “Tommy” which summarizes who many British war veterans felt following the war.

I went into a public 'ouse to get a pint o' beer,

The publican 'e up an' sez, " We serve no red-coats here."

The girls be'ind the bar they laughed an' giggled fit to die,

I outs into the street again an' to myself sez I:

O it's Tommy this, an' Tommy that, an' " Tommy, go away " ;

But it's " Thank you, Mister Atkins," when the band begins to play

The band begins to play, my boys, the band begins to play,

O it's " Thank you, Mister Atkins," when the band begins to play.

I went into a theatre as sober as could be,

They gave a drunk civilian room, but 'adn't none for me;

They sent me to the gallery or round the music-'alls,

But when it comes to fightin', Lord! they'll shove me in the stalls!

For it's Tommy this, an' Tommy that, an' " Tommy, wait outside ";

But it's " Special train for Atkins " when the trooper's on the tide

The troopship's on the tide, my boys, the troopship's on the tide,

O it's " Special train for Atkins " when the trooper's on the tide.

Yes, makin' mock o' uniforms that guard you while you sleep

Is cheaper than them uniforms, an' they're starvation cheap.

An' hustlin' drunken soldiers when they're goin' large a bit

Is five times better business than paradin' in full kit.

Then it's Tommy this, an' Tommy that, an` Tommy, 'ow's yer soul? "

But it's " Thin red line of 'eroes " when the drums begin to roll

The drums begin to roll, my boys, the drums begin to roll,

O it's " Thin red line of 'eroes, " when the drums begin to roll.

We aren't no thin red 'eroes, nor we aren't no blackguards too,

But single men in barricks, most remarkable like you;

An' if sometimes our conduck isn't all your fancy paints,

Why, single men in barricks don't grow into plaster saints;

While it's Tommy this, an' Tommy that, an` Tommy, fall be'ind,"

But it's " Please to walk in front, sir," when there's trouble in the wind

There's trouble in the wind, my boys, there's trouble in the wind,

O it's " Please to walk in front, sir," when there's trouble in the wind.

You talk o' better food for us, an' schools, an' fires, an' all:

We'll wait for extry rations if you treat us rational.

Don't mess about the cook-room slops, but prove it to our face

The Widow's Uniform is not the soldier-man's disgrace.

For it's Tommy this, an' Tommy that, an` Chuck him out, the brute! "

But it's " Saviour of 'is country " when the guns begin to shoot;

An' it's Tommy this, an' Tommy that, an' anything you please;

An 'Tommy ain't a bloomin' fool - you bet that Tommy sees!I kind of felt that way when I returned from Iraq in 2008. It is something that I still struggle with, and though long home from war I often sense such thoughts and emotions.

The song, It’s a Long Way to Tipperary was written by Henry James “Harry” Williams and co-credited to his partner Jack Judge as a music hall song in 1912. It became very popular before the war, but became a world wide hit when George Curnock, a correspondent for the Daily Mail saw the Irish Connaught Rangers Regiment singing it as they marched through the Belgian port of Boulogne on August 13th 1914 on their way to face the German Army. Curnock made his report several days later, and soon many units in the British Army adopted it. It became a worldwide hit when Irish Tenor John McCormack recorded it in November 1914. The chorus goes:

It’s a long way to Tipperary

it’s a long was to go

It’s a long way to Tipperary

to the sweetest gal I know

farewell to Piccadilly

so long Leister Square

It’s a long way to Tipperary

but my heart lies there

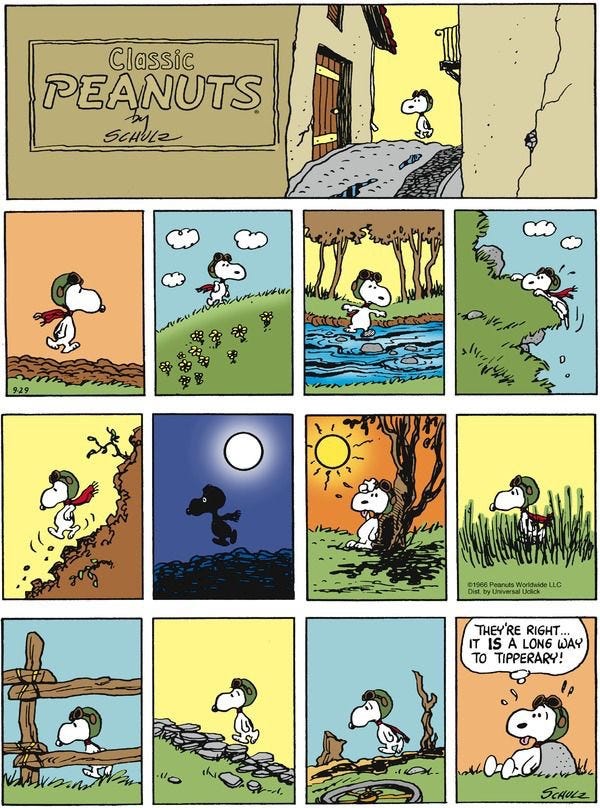

I think that the first time that I heard the song was when I saw It’s the Great Pumpkin Charlie Brown, where Snoopy as the World War One Flying Ace alternates between happiness and tears as Schroeder plays the song on his piano. In a number of later comic strips, Charles Schulz, had Snoopy refer to it a number of times, in one strip, exhausted by his march, a tired Snoopy lays down and notes:“They’re right, it is a long way to Tipperary.” I do understand that.

George Santayana was visiting England after the war and wrote a soliloquy called Tipperary after watching on the wounded officers singing the song in a coffee house and he wonders if they understand how different the world is now. He wrote:

I wonder what they think Tipperary means for this is a mystical song. Probably they are willing to leave it vague, as they do their notions of honour or happiness or heaven. Their soldiering is over; they remember, with a strange proud grief, their comrades who died to make this day possible, hardly believing that it ever would come; they are overjoyed, yet half ashamed, to be safe themselves; they forget their wounds; they see a green vista before them, a jolly, busy, sporting, loving life in the old familiar places. Everything will go on, they fancy, as if nothing had happened…

So long as the world goes round we shall see Tipperary only, as it were, out of the window of our troop-train. Your heart and mine may remain there, but it s a long, long way that the world has to go.”

In the same work Santayana mused on the nature of humanity and war, making one of his most famous observation “only the dead have seen the end of war.

When I re-read Santayana words I came back to his observation of the officers that he saw in the coffee house and I could see myself in them:

“I suddenly heard a once familiar strain, now long despised and out of favour, the old tune of Tipperary. In a coffee-house frequented at that hour some wounded officers from the hospital at Somerville were singing it, standing near the bar; they were breaking all rules, both of surgeons and of epicures, and were having champagne in the morning. And good reason they had for it. They were reprieved, they should never have to go back to the front, their friends such as were left could all come home alive. Instinctively the old grumbling, good-natured, sentimental song, which they used to sing when they first joined, came again into their minds.

It had been indeed a long, long way to Tipperary. But they had trudged on and had come round full circle; they were in Tipperary at last.”

I cannot speak for all who have been changed by war, by those words mirror my feelings.

Marine Corps General, Smedley Butler who rose from the ranks and was awarded the Medal of Honor twice during his career wrote the ultimate treatise on the cost of war. His book, War is a Racket, was published in 1935 following his forced retirement from the Marine Corps. He had earned the ire of President Herbert Hoover for his criticism of the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini. Political and public pressure kept Hoover from having Butler tried by Courts Martial. However, Hoover prevented Butler from being named Commandant of the Marine Corps. In 1934 he was approached by business leaders, fascists, and veterans who opposed Franklin Roosevelt to lead a half-million man “army” to overthrow the government. Butler refused and instead exposed the plot to overthrow American democracy. Butler wrote:

WAR is a racket. It always has been. It is possibly the oldest, easily the most profitable, surely the most vicious. It is the only one international in scope. It is the only one in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives. A racket is best described, I believe, as something that is not what it seems to the majority of people. Only a small “inside” group knows what it is about. It is conducted for the benefit of the very few, at the expense of the very many. Out of war a few people make huge fortunes. In the World War a mere handful garnered the profits of the conflict. At least 21,000 new millionaires and billionaires were made in the United States during the World War. That many admitted their huge blood gains in their income tax returns. How many other war millionaires falsified their income tax returns no one knows…

Out of war nations acquire additional territory, if they are victorious. They just take it. This newly acquired territory promptly is exploited by the few—the self-same few who wrung dollars out of blood in the war. The general public shoulders the bill. And what is this bill? This bill renders a horrible accounting. Newly placed gravestones. Mangled bodies. Shattered minds. Broken hearts and homes. Economic instability. Depression and all its attendant miseries. Back-breaking taxation for generations and generations…

But the soldier pays the biggest part of the bill. If you donʼt believe this, visit the American cemeteries on the battlefields abroad. Or visit any of the veteransʼ hospitals in the United States. On a tour of the country, in the midst of which I am at the time of this writing, I have visited eighteen government hospitals for veterans. In them are a total of about 50,000 destroyed men—men who were the pick of the nation eighteen years ago. The very able chief surgeon at the government hospital at Milwaukee, where there are 3,800 of the living dead, told me that mortality among veterans is three times as great as among those who stayed at home.

Boys with a normal viewpoint were taken out of the fields and offices and factories and classrooms and put into the ranks. There they were remolded; they were made over; they were made to “about face”; to regard murder as the order of the day. They were put shoulder to shoulder and, through mass psychology, they were entirely changed. We used them for a couple of years and trained them to think nothing at all of killing or of being killed.

Then, suddenly, we discharged them and told them to make another “about face”! This time they had to do their own readjusting, sans mass psychology, sans officersʼ aid and advice, sans nation-wide propaganda. We didnʼt need them any more. So we scattered them about without any “three-minute” or “Liberty Loan” speeches or parades. Many, too many, of these fine young boys are eventually destroyed, mentally, because they could not make that final “about face” alone.

In the government hospital at Marion, Indiana, 1,800 of these boys are in pens! Five hundred of them in a barracks with steel bars and wires all around outside the buildings and on the porches. These already have been mentally destroyed. These boys donʼt even look like human beings. Oh, the looks on their faces! Physically, they are in good shape; mentally, they are gone. There are thousands and thousands of these cases, and more and more are coming in all the time. The tremendous excitement of the war, the sudden cutting off of that excitement—the young boys couldnʼt stand it.

Thatʼs a part of the bill. So much for the dead—they have paid their part of the war profits. So much for the mentally and physically wounded—they are paying now their share of the war profits. But the others paid, too—they paid with heartbreaks when they tore themselves away from their firesides and their families to don the uniform of Uncle Sam—on which a profit had been made. They paid another part in the training camps where they were regimented and drilled while others took their jobs and their places in the lives of their communities. They paid for it in the trenches where they shot and were shot; where they went hungry for days at a time; where they slept in the mud and in the cold and in the rain—with the moans and shrieks of the dying for a horrible lullaby.

Today some will mark the day at ceremonies marking the event, others will reflect with other veterans and share their stories and pictures of their service in war and peace. As a man that spent nearly 40 years in the Army and Navy, including two combat tours, I tend to be somewhat melancholy and reflective. I am one of those that deals with severe PTSD and other afflictions, but I am proud of my service and honored to serve with the men and women with who I had the privilege of serving.

But, even so, I am damaged. Sleep is a priceless commodity to me. I suffer terrible nightmares and night terrors, which coupled with a REM sleep disorder when my body does not shut down whenI reach REM sleep, means that I act out those dreams, sometimes throwing myself out of bed. This resulted in several ER visits, and other doctors visits, the most recent being two and a half weeks ago where I hurt my back.

The American Civil War Hero, General Gouverneur Warren, who helped save the day for the Union at the Battle of Gettysburg wrote after the war:

“I wish I did not dream that much. They make me sometimes dread to go to sleep. Scenes from the war, are so constantly recalled, with bitter feelings I wish to never experience again. Lies, vanity, treachery, and carnage.”

I am also reminded of the words of Guy Sajer in his book The Forgotten Soldier. Sajer was a French Alsacian of German descent who spent nearly four years fighting as an ordinary infantry soldier on the Eastern Front. When he returned home he struggled and he wrote:

“In the train, rolling through the sunny French countryside, my head knocked against the wooden back of the seat. Other people, who seemed to belong to a different world, were laughing. I couldn’t laugh and couldn’t forget.”

A similar reflection was made by Erich Maria Remarque in All Quite on the Western Front:

“I imagined leave would be different from this. Indeed, it was different a year ago. It is I of course that have changed in the interval. There lies a gulf between that time and today. At that time I still knew nothing about the war, we had been only in quiet sectors. But now I see that I have been crushed without knowing it. I find I do not belong here any more, it is a foreign world.”

I have to admit that for the better part of the past thirteen years, when I get out of my safe spaces I often feel the same way. I don’t like crowded places, confined areas and other places that I don’t feel safe in. When I am out I always am on alert, and while I don’t have quite the hyper-arousal and hyper-vigilance that I once lived with, I am much more aware of my surroundings and always plan an escape route from any public venue that I happen to find myself.

With that I leave you with Sir Elton John’s song Oceans Away which he wrote to commemorate the fallen from the First World War on it’s centenary.

Profoundly moving.

Don’t know how l missed your exhaustive first person account of life and living death as a survivor of the military. But now that the hostage release is underway in Israel, l can begin to breathe a sigh of relief, at least until the final impact resumes its grim tally.

There is a deep divide between the idea of “serving your country”, and the debilitating effects of actually sacrificing your peace of mind, if not your life and limb.

I’m gratified that you have found your way to Substack through the posts of Lucian. His place in history is well defined and his willingness to explore and expose his own disappointments is exemplary. This Substack platform provides for multi/layered conversations to expand the playing field, opening connections between the participants. Here we engage in discourse and revive our own search for a way to articulate the inescapable malaise that is keeping us up at night.

Your work deserves to be studied, not just perused. The consolation for this reader is your courageous approach to history and your willingness to share, even the most difficult challenges, with a clarity that is invigorating.

The pity is that it is not widely known, but; it is ongoing and this makes it all the more vital!